Albert Kahn’s story blew me away. According to the blurb of the book: “Kahn used his vast fortune to send a group of intrepid photographers to more than fifty countries around the world, often at crucial junctures in their history, when age-old cultures were on the brink of being changed for ever by war and the march of twentieth century globalisation.” Nobody really knew about Kahn’s collection – numbering more than 72,000 autochromes – until quite recently. Now, thanks to the dusty compilers at the BBC, we’re finally giving some colour to what we have tended to imagine as an utterly foreign, black-and-white age.

When the Chinese Qing Dynasty collapsed in 1911, their former subjects in Mongolia quickly declared independence. This was challenged by the newborn Republic of China, however, whose forces eventually managed to reconquer the country while the other regional powerhouse, Russia, was distracted with its revolution. But China’s tenure was brief: a renegade anti-Communist army from Russia soon seized control of the country. This photograph was taken a mere two years after Mongolian independence, and six years before the Chinese and Russian invasions. I can only wonder what might have happened to this wolf- and fox-hunter, who seems to have lived somewhere near the border with Russia.

The Kurds are a people with a complicated, and often difficult history. Overlapping the borders of modern-day Iran, Syria, Turkey and Iraq, they still lack a country of their own – despite frequent conflicts with the governments who rule over them. As long ago as 1920, the Kurds were promised an independent homeland by the Allied victors of WWI. This promise wasn’t kept. More recently, the Kurds – some of them perhaps the descendants of these girls in the photograph – suffered genocide at the hands of murderous Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. If the Iraq War can at all be justified, it can be justified by the fact that since the arrival of U.S. and allied troops, this genocide has ceased, or at least slowed.

This disturbing photograph was taken soon after the Second Balkan War, which saw the Bulgarians battling against their former allies from the First Balkan War, Greece and Serbia. The second war essentially took place after a quabble over the division of spoils from the first war. The well-dressed young man in the photo – probably an ethnic Bulgarian – has been arrested by Greek soldiers near a monastery on Mt Athos. His fate remains unknown. To include him among the victims of ethnic cleansing, which was widespread at the time, might be stretching things a little bit – he could well have been a highwayman who roamed and robbed among these hills. The Balkan Peninsula, at the eastern edge of civilised Europe, remains one of the most volatile parts of the world, having seen multiple genocides in the past twenty years. A good book to read is the travelogue “Black Lamb and Grey Falcon”, by Rebecca West.

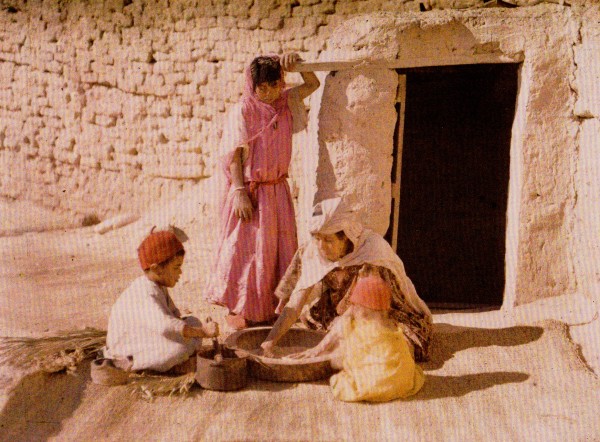

This family is preparing couscous, which has long been a staple food for the people of North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Tunisia, and Morocco. The young boy in the red cap would be about one hundred and ten years old, if still alive today.

The sharing of betel nuts is an important tradition in many Asian countries, including Vietnam. The nuts are supposed to have a range of health benefits, such as the prevention of tooth decay – which might seem unlikely to anyone who has seen the bright red stains left by the juice on teeth across Asia. Recent research has even suggested a correlation between oral cancer and betel consumption. This does nothing to diminish the human value of this photo, however, which – unlike many photos from the time – captures an informal, quiet, and rather beautiful moment, experienced by these two village girls so many years ago.

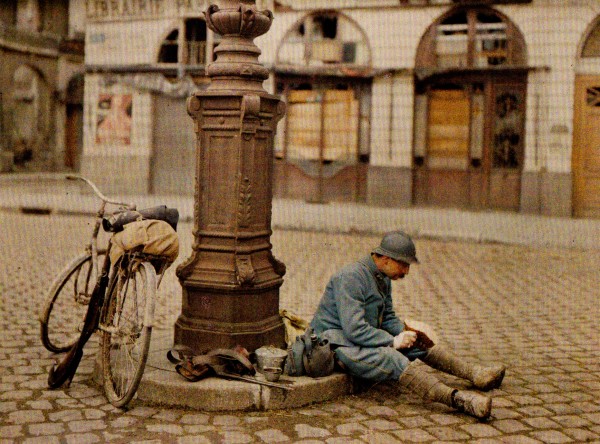

Three years into World War One, the Allied army still relied on bicycle messengers to pass information down the lines. They also had telegraph and telephone lines, but these were vulnerable to sabotage, and to falling German shells. This messenger, during a moment of respite, is enjoying a hunk of bread and a pot of tea. Well-deserved, I say.

These children are playing amongst the ruins of Reims, 129km northeast of Paris. As it lay near the Western Front, Reims was greatly damaged by German bombardment and subsequent fires during the hostilities of WWI.

Rabindranath Tagore, one of the most famous contributions India has made to the world of literature, is seen here surrounded by the roses of Albert Kahn’s garden. Tagore – a native of Calcutta – was awarded the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature, mainly for his contributions to poetry. He also fancied himself as a mystic philosopher, and certainly looked the part. The esteemed Western philosopher Bertrand Russell, however, was unimpressed: “Here I am back from Tagore’s lecture,” he wrote in his diary, “after walking most of the way home. It was unmitigated rubbish: cut-and-dried conventional stuff about the river becoming one with the Ocean and man becoming one with Brahma. The man is sincere and in earnest but merely rattling old dry bones. I spoke to him before the lecture, but afterwards I avoided him.”

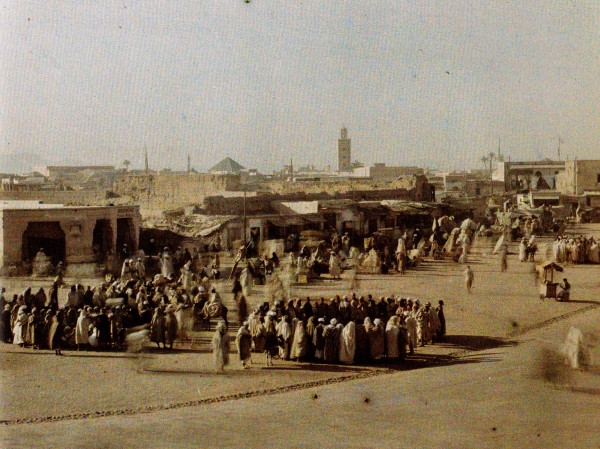

Jemaa el-Fnaa, as it is called in Arabic, is still today the main square of Marrakesh – a city famed for its Spanish-influenced mosques, its red sandstone buildings, and its exotic, windswept appearance. The most striking thing about this photograph, in my opinion, is the effect caused by the time delay: many of the people in the frame – such as the huddle of religious devotees, the camouflaged camel, and the solitary vender – are in perfect focus. But others – the blurry figures – give a strong suggestion of movement, and make it seem like the photo could have been taken yesterday. A second glance at the date reminds me that my grandparents were toddlers at the time of exposure.

This is one of the best WWI photos I have seen. It has none of the usual distant and archaic feel to it; instead, I can imagine myself being in the room at the time. It’s easy to imagine the wounded soldiers talking to the nurse, or raising that bottle of wine to their lips. I highly recommend searching for the book in your local library, so you can see all these photos at their magnificently full size.

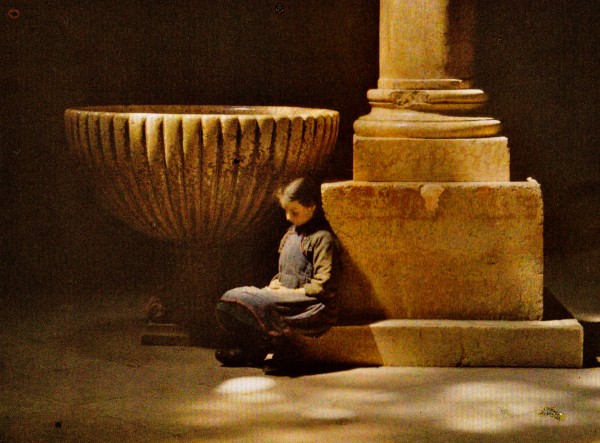

Apparently, this photograph – shot in the vault of a church in Verona – required an exposure time of more than a minute. The effect is reminiscent of Rembrandt or Van Dyck; the dappled sunlight on that pillar, on that floor, is photography at its best. But for me, it’s enough to contemplate the fate of the girl, lost in reflection, visualising thoughts which on that day in 1918 belonged to her and her alone.

“What passing-bells for these, who die as cattle?” asked the young wartime poet Wilfred Owen, shortly before perishing in the war himself: — Only the monstrous anger of the guns. Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle Can patter out their hasty orisons. No mockeries now, for them; no prayers, nor bells; Nor any voice of mourning, save the choirs, — The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells; And bugles calling for them from sad shires. What candles may be held to speed them all? Not in the hands of boys but in their eyes Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes. The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall; Their flowers, the tenderness of patient minds, And each slow dusk, a drawing-down of blinds.

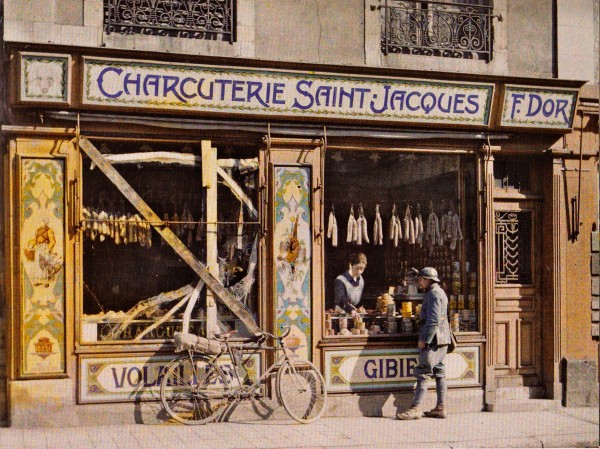

A charcuterie is a French butchery which, before the age of refrigeration, specialised in providing customers with cold, well-preserved meats. This particular store, in Reims, is surprisingly well-stocked: it seems that the soldier, who was probably on R&R, didn’t lack for choice. Note the flimsy attempt at a barricade on the left-hand window: as has been said above, this city suffered a great deal from German bombardment. It is remarkable that ordinary life seems to have ticked along in Reims, throughout wartime. A marked difference, perhaps, from the flexible front-lines of World War Two.

The girl plays with her doll, and rifles lean against the wall, right beside her, as the Great War continues. That’s a powerful juxtaposition if I’ve ever seen one – it’s easy to forget what many soldiers believed they were fighting for. If you’re excited or moved by these photographs, check out Jamie’s list of colour photographs from specifically World War One.

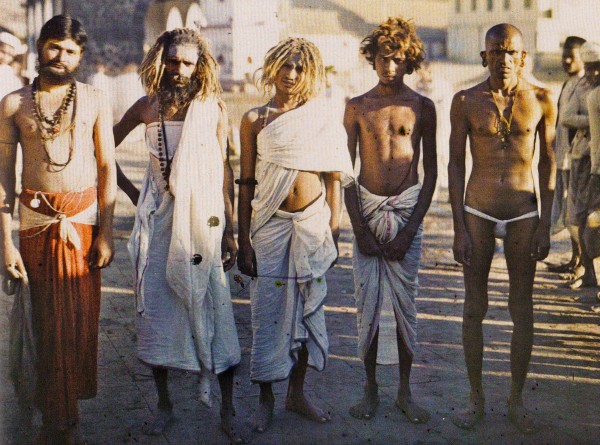

This image, more than any other on the list, shows timelessness. If you search for images of Indian Sadhus, or holy men, today, you’ll see clothes, bodies, customs and faces which exactly resemble those of the men in this 99-year-old photo. The sadhus in question were most likely out-of-towners – visitors to the bustling colonial city of Bombay, which is now the most populated city in India. Bombay, or Mumbai as it has been called since Hindu nationalists forced a name-change, incidentally remains an incredible destination for travel today. Slumdog Millionaire is one facet of the enormous city: but it also features an engrossing hodge-podge of history, culture, food, entertainment (especially film), and people as diverse as you can imagine – the sadhus, in particular, haven’t changed.

The nomads of Mongolia developed a justice system to suit their mobile lifestyle. Seen here is a criminal, attached to a chain so heavy as to prevent him from running very far across the empty steppe. At the same time, he would be capable of a (most likely excruciating) forced march, from grazing ground to grazing ground – wherever his elders might see fit to travel.