10 Ruhnama

Saparmurat Niyazov, the late president-for-life of Turkmenistan, wrote a book known as the Ruhnama, meaning “Book of the Soul,” published in 2001. According to the dictator, it was meant to improve the spiritual life of the Turkmen people. Niyazov even claimed that God had assured him that readers of the book would surely get into Heaven. His book was mandatory reading in schools and universities and displayed next to the Quran in mosques, and there was even a test on the Ruhnama included in the process of getting a driver’s license. Elaborate ceremonies saw hundreds of Turkmen engaged in choreographed songs and dances while holding the book. In the capital of Ashgabat, a giant statue of the book was built, which would open and play an audio and video recording of a passage from the text. In reality, the book was just a bizarre mix of Niyazov’s morality, a lot of self-congratulation, a contrived revisionist history of Turkmenistan, and fairy tales. Niyazov’s decision to use a book to establish his regime was explained by a scholar quoted in the New Yorker: “Niyazov was somewhat illiterate. He couldn’t read or write Turkmen or Russian properly. People who have disabilities, for example illiteracy, want to be seen as geniuses. This was probably what got him started.”

9 On the Art Of Cinema

Kim Jong Il was a big movie buff and considered himself somewhat of an expert. In 1973, he published On The Art of Cinema, following it up in 1987 with The Cinema and Directing. For Kim, building a good film industry was a socialist project: Art and literature are important activities which are indispensable to a fully human life. Food, clothing, and housing are the essential material conditions for human existence, but man is not satisfied with these alone. The freer man is from the fetters of nature and society and from worries over food, clothing and housing, the greater his need for art and literature. Life without art and literature is unimaginable. Much of the problem with Kim’s advice regarding cinema is how obvious it is. Perhaps the idea is of profundity within simplicity, but we suspect it has more to do with fact that he didn’t have many original things to say. Here is his opinion on repeated viewings: Seeing a production once is different from seeing it twice. One wants to see some productions again, but not others. A certain production awakens fresh interest each time one sees it and excites greater passion and warmth. This sort of production is called sincere art. As for music: Sound and music are heard wherever nature works and man lives. [ . . . ] However excellent the music, it is useless for the cinema if it is not appropriate to each scene.” The turgidity and rigidity of the text is probably one of the best arguments that the text was indeed written by Kim himself. However, he did gain some interest abroad. Australian documentarian Anna Broinowski was intrigued by Kim’s directing advice and decided to produce a propaganda movie following the Dear Leader’s instructions in order to protest a gas company drilling in a park near her home. When she asked directing advice from North Korean filmmakers, she found herself given unprecedented access to the entire North Korean film industry, including interviews with North Korean directors and actors. Broinowski was even given the opportunity to appear in a North Korean film herself, playing an evil American, though she apparently flubbed her lines.

8 The Wine Of Love

Ayatollah Khomeini was a surprisingly prolific writer, penning commentaries on the Quran and the Hadith, as well as works on Islamic law, philosophy, gnosticism, poetry, literature, and politics. Unlike the literature of most other authoritarian leaders, the works of the ayatollah were rarely translated. After the Islamic Revolution, a hastily assembled paperback was published called The Little Green Book: Sayings of the Ayatollah Khomeini. However, after being translated from Iranian to French to English, it somehow went from over 1,000 pages to only 125, with a suspiciously repeated theme of aphorisms about semen, sweat, and the anus, adding weird color to the reactionary thoughts of the ayatollah. Following that, a book by a more sympathetic author was published in 1981, called Islam and the Revolution. It established Khomeini’s credentials as a righteous-minded revolutionary while insisting that his ideology was derived from classical Islam, shariah law, and the Sufi tradition. Less well-known in the West was the revolutionary imam’s flair for mystical poetry, compiled in a collection called The Wine of Love. To Western eyes, the poetry seems strangely heretical but apparently is part of a long tradition of poetry written as part of a deeply personal communion with God. One example is a translation of one of the ayatollah’s poems, published in an Iranian newspaper in 1989: Open the door of the tavern and let us go there day and night, For I am sick and tired of the mosque and seminary. I have torn off the garb of asceticism and hypocrisy, Putting on the cloak of the tavern-haunting shaykh and becoming aware. The city preacher has so tormented me with his advice That I have sought aid from the breath of the wine-drenched profligate. Leave me alone to remember the idol-temple, I who have been awakened by the hand of the tavern’s idol.

7 Enver Hoxha’s Books

Paranoid even by communist standards, Albania became increasingly isolated after its leader, Enver Hoxha, fell out with Soviet leader Khruschev over the end of Stalinism. He also fell out with China, Albania’s one remaining ally. In hermetic isolation, Albania became subject to the crimes against literature committed by Hoxha, who would eventually churn out 40 volumes of speeches and memoirs. His writings reflected his mindset and deep distrust of the outside world and foreign imperialists: Both the bitter history of our country in the past and the reality of the ‘world’ that they advertise have convinced us that it is by no means a ‘civilized world,’ but a world in which the bigger and stronger oppress and flay the smaller and the weaker, in which money and corruption make the law, and injustice, perfidy and backstabbing triumph. One of his most famous works was With Stalin, written in 1979 in memory of Hoxha’s hero, Joseph Stalin. The book is divided into six sections—an introduction and five collections of reminiscences of the Albanian leader’s encounters with the Soviet strongman. It is a shockingly boring hagiography meant to celebrate the extinct Stalin personality cult while reinforcing Hoxha’s own. Hoxha wrote lovingly of Stalin, reporting dreaming night and day of his eventual meeting with Stalin and of the viewing of a Soviet musical entitled Tractor Drivers. Much of the book is also devoted to lambasting his real and perceived enemies, both Western “imperialists” and his many, many foes within the communist world itself. Regardless of Hoxha’s prolific output, the collapse of communism in Albania relegated his work to history books. In 1991, pro-democracy protesters burned the late dictator’s works in a crater near a toppled Hoxha statue. By the mid-1990s, pages from Hoxha’s works were being used to wrap roasted peanuts and sausages. Today, Hoxha’s books are still sold, but now, they’re alongside the works of liberal poet and novelist Ismail Kadare, as well as Western authors like Danielle Steele and L. Ron Hubbard.

6 Akhaltekke: Our Pride And Glory

Saparmurat Niyazov’s successor to the rule of Turkmenistan, Gurbanguli Berdymukhamedov, was not about to let the rich tradition of Turkmen dictator literature die with the passing of the old leader. His first book, published soon after assuming power in 2007, was a tad too prosaic—Scientific Fundamentals of the Development of Public Health in Turkmenistan. This was followed up by an exciting collection of political speeches called To New Heights of Progress: Selected Works—or Speech of the President of Turkmenistan Gurbanguli Berdymukhamedov at the Extended Sitting of the Cabinet of Ministers. Needless to say, these were largely for a domestic audience only. In 2009, however, he secured his first international book release for his masterpiece Akhaltekke: Our Pride and Glory, published in Ukrainian. The book was a loving ode to the Akhal-Teke horse breed and the history of horse breeding in Turkmenistan. The cover featured an image of a smiling Berdymukhamedov standing with a proud Akhal-Teke steed. It would later be published in French, English, Russian, and German, though its success abroad has so far been lackluster. It did, however, allegedly receive some accolades within the Community of Independent States (CIS), winning the CIS member states’ international contest called “Art of Book” in the “My Country” nomination.

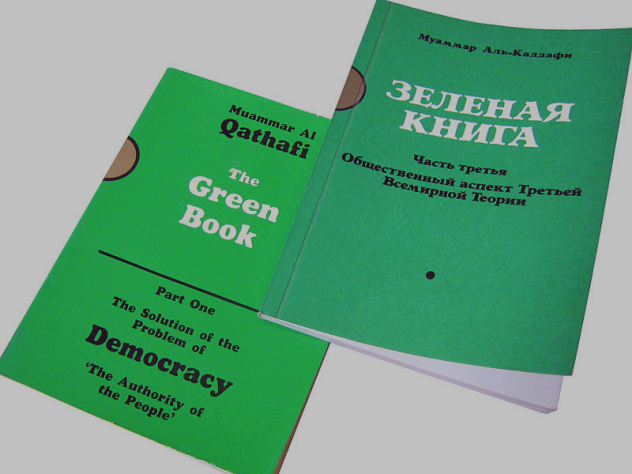

5 Green Book

Muammar Gadhafi’s Green Book, a 1975 work of political and social philosophy, was once a nearly omnipresent feature of Libya’s literary universe. The work described Gadhafi’s Islamic socialist vision of Jamahiriya, a democratic system without parties governed directly by the people. The first volume of the Green Book, titled “The Solution of the Problem of Democracy,” criticized both communism and Western democracy, decrying elections, political parties, and popular representation as fraudulent. True democracy was achievable only through the people coming together in people’s committees, popular congresses, and professional associations. In reality, this was little more than a guise for a personal military dictatorship with Gadhafi at the helm. The second volume of the book was on economic theory, titled “The Solution of the Economic Problem.” Here, many of the contents were a mess of capitalist and socialist ideology which has been compared with the thoughts of Rousseau, Mao, and Marx, as well as Islamic philosophy. Property ownership was given much importance, with Gadhafi insisting, “There is no freedom for a man who lives in another’s house, whether he pays rent or not.” During the 1980s, Gadhafi attempted to institute many of these policies in Libyan society, creating a government-run supermarket system and forcing families to own only one home. The main result of the policies were the decimation of the traditional Libyan merchant class. He also had some choice information about the difference between the sexes: Women, like men, are human beings. This is an incontestable truth . . . Women are different from men in form because they are females, just as all females in the kingdom of plants and animals differ from the male of their species . . . According to gynecologists women, unlike men, menstruate each month . . . Since men cannot be impregnated they do not experience the ailments that women do. She breastfeeds for nearly two years. Gadhafi was inspired as much by the earlier writing of Egyptian nationalist Gamal Abdel Nasser as he was by the traditional Bedouin lifestyle. A Tripoli think tank known as the The World Center for the Study and Research of the Green Book attempted to popularize the dictator’s writing overseas. They translated the work into 30 languages, underwrote international conferences, and released nearly 140 studies and scholarly papers on Gadhafi’s theories. The work never really caught on, though, and the think tank was eventually destroyed by NATO air strikes in 2011.

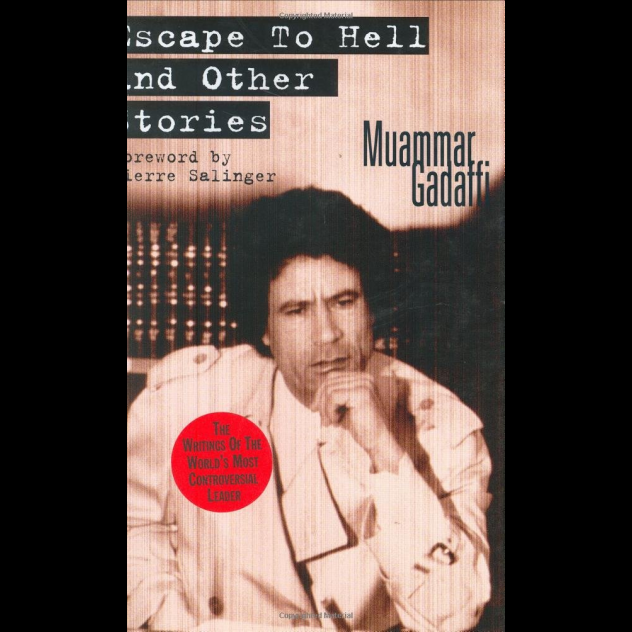

4 Escape To Hell

Gadhafi wasn’t just content churning out political literature, he also tried his hand at short stories, releasing two collections, Escape to Hell (1993) and Illegal Publications (1995). The main problem with Gadhafi’s short stories is that he doesn’t really understand the art of prose. There are no characters and little narrative but rather bizarre stream of consciousness rants. Many of the pieces highlight Gadhafi’s preference for village life and the way of the Bedouin rather than the alienating existence of the city: This is the city: a mill that grinds down its inhabitants, a nightmare to its builders. It forces you to change your appearance and replace your values; you take on an urban personality, which has no colour or taste to it . . . The city forces you to hear the sounds of others whom you are not addressing. You are forced to inhale their very breaths . . . Children are worse off than adults. They move from darkness to darkness . . . Houses are not homes—they are holes and caves . . . Another bizarrely compelling piece was “Suicide of The Astronaut,” telling the story of a space explorer who returns to Earth and is unable to find suitable employment. He tries and fails to find work in carpentry, lathing, blacksmithing, building, plumbing, and white-washing before fleeing the city into the countryside. There, he tries and fails to explain his plight to an uncomprehending farmer, who ultimately feels sympathy for the erstwhile astronaut but declines to take him on as a farm hand, leading the space man to commit suicide out of earthly ennui. The short stories of Gadhafi are often entertaining for their vitriol, focused on both the West and Islamic fundamentalist thinkers. He enjoyed making frequent references to classical Islamic thought, though his own religious views were highly idiosyncratic and heterodox. Though they were published in English, there wasn’t a great deal of praise in the West for Gadhafi’s stories. Daniel Kalder would write in the Guardian: “What we find is a mind that cannot follow a coherent thought for very long, is filled with crude dichotomies and nonsense, and rambles along at random, collapsing in on itself before exploding outward again in a burst of surreal gibberish.”

3 Masoneria

Spanish dictator Francisco Franco had a lifelong suspicion of the Freemasons, whom he perceived as a conspiracy to undermine Catholic Spain and banned along with communism in 1940. Between late 1947 and early 1951, Franco wrote a series of anti-Mason articles in the Falange journal Arriba, after which they were collected in a text called Masoneria under his pseudonym, J. Boor. Franco allegedly suspected the book was being bought up by the Freemasons themselves to prevent it from being written and tried to encourage an English-language version, though it never came to fruition. While the book is available online in Spanish, there is little available information on the text in English. What little exists is often linked to lurid conspiracy websites. One compelling piece of text illustrates Franco’s conspiratorial mindset linked Freemasonry, communism, and Judaism: Another focal point of this Soviet infiltration which Freemasonry presents us is that of the State of Israel, where, under the pretext of creating a Jewish religious state, there has taken place a concentration of atheist elements from Central Europe and the international bas fonds (lower strata), who eventually regard as Pharisaic and backward the ministers and representatives of the Mosaic faith. What was to have been a Jewish state, built on the old models of international Jewry, has thus become a focal point of faithless and rootless people, receptive to foreign slogans and influences. Russia takes advantage once again of the state of affairs which Freemasonry offers to her to serve its own interests. Russia was aware of the great influence of Judaism in American politics, and the presence in many governments in Europe and in America of leading members of the Masonic sects; the oath they took when going through the XV and XVI degrees of ‘Knights of the Orient or of the Sword’ and ‘Princes of Jerusalem;’ regarding ‘turning over to the Hebrew people all that which was taken away from them by force,’ and while it helped and supported Stern Gang’s terrorist attacks in the Middle East, it worked in international meetings to foster Zionist principles, which would take their struggle to the field of their enemies, since for Russia, before the war, during the war and after the war, the nations which will not submit will always be its enemy. [ . . . ] The creation of Israel was of Soviet work. Here, as in the case of Lie, President Ben Gurion also presents himself with the complexity of his dual nationality, for he was active in the Communist ranks under a different name. Let us not lose sight of the diminutive State which, small as it may be, is ambitious in its aspirations, which reach to the limits of the Euphrates, and, however farfetched it may seem to us, there are those who feed the fire which one day may become a devouring wild fire, behind which the tanks of the modern barbarians will surge forward.

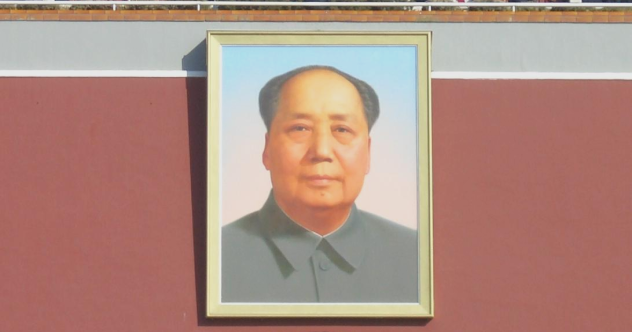

2 Mao’s Poetry

Chinese revolutionary leader Mao Tse-tung wrote a number of books, most famously his political treatise The Little Red Book. However, what is less well-known is that his education was steeped in classical Chinese culture, and he grew up with a love of calligraphy and traditional forms of poetry. Over four decades, spanning the pre- and post-revolutionary periods, Mao produced scores of poetic works that were then translated into English, with titles like “Yellow Crane Tower” (1927), “The Long March” (1935), “The People’s Liberation Army Captures Nanking” (1949), “Farewell To the God Of Plague” (1958), and “The Fairy Cave: Inscription on a Photograph taken by Comrade Li Chin” (1961). Many of his poems were inspired by the literary traditions of the Tang and Sung dynasties. Opinions on Mao’s poetry vary depending on the source. According to the Chinese, it “exhibits a spirit of boldness and power, weaving together history, reality and commitment, and going beyond the limitations of time and space. [ . . . ] Mao Zedong advocated a method of literary composition that combines revolutionary realism and revolutionary romanticism, and his poetry was a synthesis of his theory and practice.” Belgian sinologist Pierre Ryckmans was less impressed, saying, “Well, if poetry were painting, I would say that Mao was better than Hitler . . . but not as good as Churchill.” Mao, for his part, modestly called them “scribbles.” Mao did seem to have a literary flair, with an appreciation for natural themes like flowers, snow, horses, geese, sky, rivers, mountains, and the Moon. But his poems also occasionally reflect the vanity of the human will, as in his work “To Guo Moruo”: On our small planet a few houseflies bang on the walls. They buzz, moan, moon, and ants climb the locust tree and brag about their vast dominion.

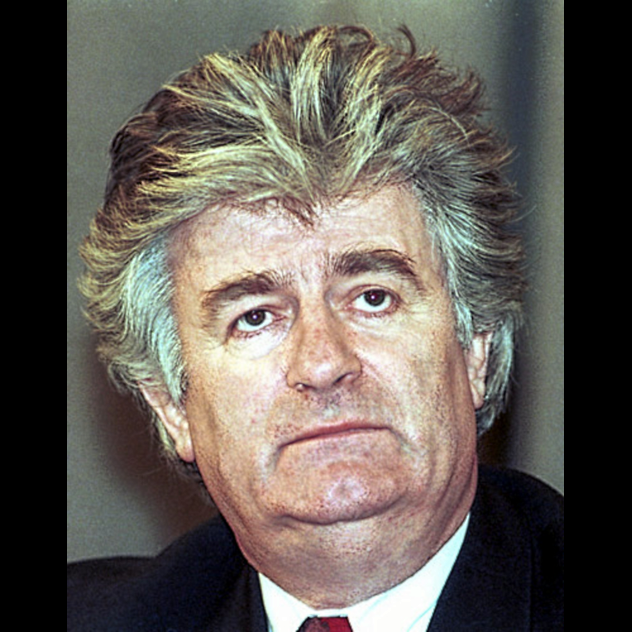

1 Under The Left Breast Of The Century

Former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic was a Columbia University–trained psychiatrist who led the violent siege and ethnic cleansing of Sarajevo in an attempt to wipe out the populations of Jews, Muslims, and Croats and create an ethnically pure Serbia. He was also a poet and author, whose work Under the Left Breast of the Century was published in 2005 in spite of Karadzic being a wanted war criminal with a $5 million bounty on his head. Much of Karadzic’s poetry often had warlike themes, with titles like “A Morning Hand Grenade,” “Assassins,” and “A Man Made of Ashes and War Boots.” But they also betrayed the dictator’s flair for self-pity: I surmise the sun is wounding me With its sharp malignant rays I surmise the stars are healing me I am the deity of dark cosmic space A horned cow reveals a faithless goddess Everything’s turned against me the one true god I created the world to tear my head off Judges torture me for insignificant acts I am disgusted by the souls who radiate nothing Like a small nasty puppy puny death Is approaching from afar I don’t know what to make of all these things But I can’t stand the sight of you you file of scum You file of snails Well hurry up in your slime After Karadzic’s capture in 2009, the Slovakian PEN Centre, part of PEN International, ethically criticized Slovakian magazine Dotyky for publishing his poetry without editorial comment. The editor defended the decision, saying simply that the poems were high-quality, but it set off a debate about free speech in publishing the works of a man known for inciting ethnic hatred. Andrew Rubin described the work as “a psychic landscape of eerie and illogical violence,” while Jay Surdukowski asserted that Karadzic saw himself as a poet-warrior. Surdukowski also argued in 2005 that the poetry itself could be admissible as evidence in a war crimes tribunal. David Tormsen hopes he won’t have to seize control of a nation state in order to get a book published. Email him at [email protected].