To “purify” Cambodia from the evils of capitalism and foreign influence, millions of people were forcibly evacuated from the cities and made to work in the countryside under inhumane conditions. Private property, religion, and money were all banned. Critics, intellectuals, and middle-class people were executed by the hundreds of thousands, and many others perished from starvation and overwork. By the time Vietnam invaded Cambodia and overthrew the Khmer Rouge in 1979, over a quarter of the Cambodian population had died, many of them buried in mass graves known as the “killing fields.”

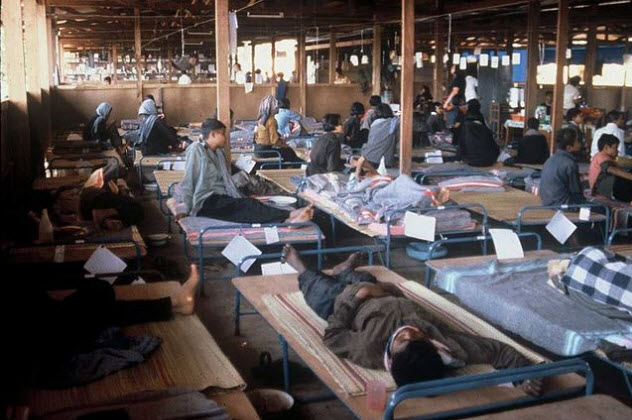

10 Security Prison 21

A secret to the world and even to Cambodia until it was discovered by two Vietnamese photojournalists in January 1979, the Security Prison 21 (“S-21”) was a former high school that was used to hold more than 15,000 people during the reign of the Khmer Rouge. Only a few prisoners are known to have survived the S-21, so much of what we know about the site comes from the meticulous documentation recorded by its leaders and workers during the 3.5 years the prison was used. A person transported to the prison first had his or her picture taken, thousands of which still exist. Prisoners were relentlessly interrogated and beaten until they confessed to crimes they didn’t commit. Interrogators pulled out the prisoners’ toenails, waterboarded them, and even subjected them to medical experiments. Once a prisoner admitted to the charge of which he was accused, he was forced to write out his confession, which could be up to several hundred pages long. With prisoners sometimes having to eat insects for survival, conditions in the prison were so bad that some died before they could be executed. Today, the prison is a museum dedicated to the people who died there. Pictures of prisoners cover the museum’s walls, and prisoner confessions and government documents are also on display. When the museum was opened to the Cambodian public in July 1980, it drew an estimated 300,000 Cambodian visitors by October of that year.

9 Youk Chhang

Youk Chhang is a Cambodian humanitarian who helps to run the Documentation Center of Cambodia, a nonprofit group that has collected hundreds of thousands of documents and photographs from the Khmer Rouge’s reign of terror. Their extensive research has played a valuable role in providing evidence for the tribunals trying former Khmer leaders for their crimes. The project is a personal mission for Chhang. He and his family were victims of the Cambodian genocide. When he was only 15 years old, Chhang was publicly tortured and then imprisoned for taking mushrooms from a rice field. It didn’t matter that the mushrooms were picked for Chhang’s starving, pregnant sister. To take anything without the government’s permission was a crime against the revolution. In jail, Chhang pleaded for his life for months until an older prisoner approached the prison chief and claimed that he was the real culprit. Chhang was let go, but the older man was executed. By the time the Khmer Rouge was driven out of power, Chhang’s family had been nearly wiped out. His pregnant sister’s husband had been beaten to death for stealing food, and his sister had died after having her stomach cut open for allegedly eating the food. Chhang also lost his grandparents, three uncles, an aunt, and numerous other relatives. As horrendous as Chhang’s experience was, he told CNN that it was “a mere footnote to the millions of other Cambodians who suffered and died at the hands of this regime.”

8 Pin Yathay

Along with 18 of his family members, Pin Yathay was one of the two million people evacuated from Phnom Penh and sent to live in the countryside. As a civil servant for the previous government, Yathay had to be careful that nobody learned about his “bourgeois” past. Before he escaped from Cambodia in summer 1977, Yathay and his relatives were forced to do backbreaking labor. When his father couldn’t work any longer, his already meager rations were cut in half. He died shortly afterward, and Yathay’s mother and sisters didn’t last much longer. All three of Yathay’s children also died. One of them, a nine-year-old boy, was taken by Khmer Rouge leaders after they told Yathay that he still had “strong individualistic tendencies.” The boy died only five days after he left home. By early 1977, Yathay’s past had been exposed, and Yathay and his wife decided they would try to escape the country. Leaving their only surviving son with a couple whose children had all died, Yathay and his wife joined a group of 10 other people to make a run for Thailand. After a two-month journey, only Yathay was able to flee across the border. Yathay was one of the earliest people to bring attention to the crimes of the Khmer Rouge. In late 1979, he published an account of his experiences called Murderous Utopia. Another book, Stay Alive, My Son, followed in 1987. The second book’s title came from words he had spoken to his son before leaving Cambodia. Sadly, Yathay has never been able to find the boy, and it is unknown whether he is still alive.

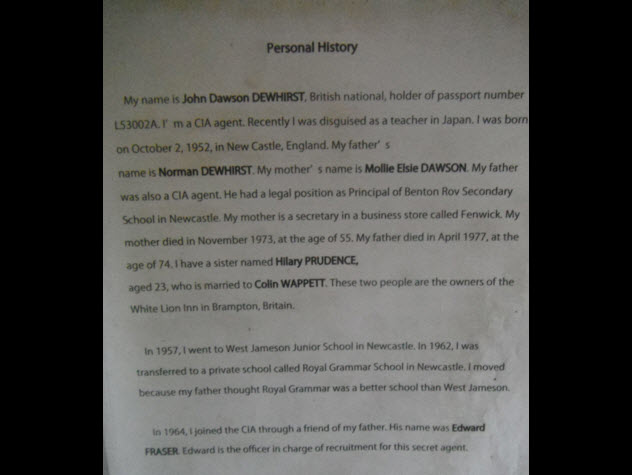

7 The Crew Of The Foxy Lady

New Zealander Kerry Hamill and Canadian Stuart Glass were two expatriate friends who enjoyed sailing on the waters of South Asia on their yacht, the Foxy Lady. In Singapore in summer 1978, they met an English teacher named John Dewhirst. Dewhirst was traveling through Asia on holiday, and Hamill and Glass invited him to come along with them to Bangkok. After stopping near the Cambodian island of Koh Tang, possibly because of a storm, the Foxy Lady was attacked by a Khmer Rouge patrol boat. Glass was shot and killed. Dewhirst and Hamill were captured and thrown in the S-21 prison. Suspecting that the two Western men were CIA agents, the Khmer Rouge tortured Dewhirst and Hamill until they falsely admitted to the accusation. In Dewhirst’s confession, he claimed that he was recruited by the CIA when he was only 12 years old and that Loughborough University, the college where he had studied, was a training ground for CIA agents. He also said that he had come to Cambodia on a spying mission and that his father was also a CIA agent. With the authorities now satisfied, Dewhirst and Hamill were sentenced to execution. We don’t know exactly what happened to the Foxy Lady’s crew. Western governments were never notified about their capture, and their families were ignorant of the crew’s fate until after the excavation of the S-21 prison. Many details—like how the men ended up in Cambodian waters as well as the method of Dewhirst’s and Hamill’s executions—will probably never be known.

6 Dith Pran

Dith Pran, the son of a public works official, was a gifted translator who worked as an interpreter for the American military from 1960 until 1965. Continuing to translate in the 1970s, he worked with Sydney Schanberg, a journalist who covered Asia and the situation in Cambodia for The New York Times. After the Khmer Rouge seized power in 1975, Schanberg was forced to leave the country, and Pran was left behind. With the Khmer Rouge in charge, Pran worked as a taxi driver and kept his past as an educated journalist and translator a secret. He was eventually exiled to the countryside, where he sometimes worked as long as 18 hours a day. Forced to eat bark and mice to survive, Pran was almost killed after he stole some rice one night. If it wasn’t for the intervention of a Khmer Rouge cadre, he would have been executed. When Pran returned to his home village after the Khmer Rouge was overthrown in 1979, he discovered that his father and four of his siblings were dead. The Khmer Rouge had treated the villagers without mercy. The remains of more than 5,000 people were buried in the forest and the village’s wells. Although Pran was put in charge of the village by the occupying Vietnamese, he fled to Thailand after his American connections were made known. Once he was out of Cambodia, Pran was reunited with Schanberg in a refugee camp. Schanberg wrote an article about Pran’s experiences the next year, and the piece later provided the plot for the award-winning 1984 film The Killing Fields.

5 Haing S. Ngor

Haing S. Ngor was the award-winning actor who played the role of Dith Pran in The Killing Fields. Interestingly, Ngor had no prior acting experience, but as he told People magazine in a 1985 interview, “I spent four years in the Khmer Rouge school of acting.” Before he was driven out of Phnom Penh in 1975, Ngor worked as a surgeon and gynecologist. As he was performing an operation, Khmer Rouge soldiers marched into the hospital room and asked if he was a doctor. Ngor replied that the doctor had just run out the back door. Fearing for his life, Ngor fled and regretfully left the patient to bleed to death. Like Pran, Ngor posed as an uneducated taxi driver. His cover was blown twice, however, and in one close incident, he was forced to remain in a hut with 180 other people as it was set on fire. Anyone who ran out was shot on sight. Only Ngor and 30 others survived the incident. By the time Ngor and a niece escaped to Thailand in 1979, most of his family, including his wife, had died. After he moved to the US in 1980 and appeared in The Killing Fields in 1984, Ngor used his fame to bring awareness and help to Cambodian genocide victims. Although he survived the ruthless Khmer Rouge, Ngor suffered a senseless, violent death in front of his home. In 1996, Ngor was ambushed by three Asian-American gangsters in a robbery. They took his gold Rolex watch but shot him to death after he refused to hand over a gold locket which contained a portrait of his dead wife. Many in the Cambodian community suspected that Ngor was killed on the orders of Pol Pot or some other Khmer Rouge official. American investigators, however, found no conclusive link between Ngor’s murderers and anyone in the former Cambodian government.

4 Cambodia’s Minorities

Although a left-wing movement, the Khmer Rouge was fiercely xenophobic. They officially claimed that Cambodia’s 24 minority groups made up not 15 percent of the population but 1 percent. Many of these minority groups were nearly exterminated during the genocide. Over 100,000 Vietnamese were kicked out of the country in 1976. Most of the 100,000 Vietnamese left behind perished in the next few years. The Chinese community, which was overwhelmingly urban, was relocated to the countryside with the rest of Cambodia’s city dwellers. Half of the Chinese population died there, many of them from hunger and disease. Especially targeted for elimination were the Cham people, a Muslim minority with a distinct culture and history from the Khmers. Mosques were destroyed, and prayer was forbidden, even at home. Korans were also banned, and according to survivor Him Soh, they were used as toilet paper. In September 1975, when the Cham village of Svay Khleang was attacked by the Khmer Rouge, the Chams put up a brave resistance using only swords and machetes. The rebellion was put down after a few days. Like the inhabitants of many other Cham villages, the people of Svay Khleang were removed and then scattered over the country. The exact death toll for the Chams has never been clearly established. Estimates range between 100,000 and 400,000 deaths.

3 Cambodia’s Buddhist Monks

Before 1975, Theravada Buddhism had been the dominant religion among the Khmer people since the late 13th century. Buddhist temples, known as wats, served various functions in their communities, including teaching young people and providing welfare for the poor and sick. They were an important national institution, but the Khmer Rouge considered Buddhism a reactionary religion and was determined to wipe out its influence throughout the country. Buddhist monks were mocked and humiliated. In a cruel joke that disobeyed their dietary laws, they were forced by the Khmer Rouge to drink alcohol and eat large meals. Books of Buddhist scriptures were burned, and temples were destroyed. Many monks were sent to work in the countryside, where they died from starvation and overwork. The wats they left behind were used as torture chambers and storage centers, with some even used to hold pigs. In 1975, the government counted 66,000 monks living in 4,000 wats. A 1989 report estimated that 25,000 monks had been executed, and half of the wats had been destroyed. Today, Buddhism has been reestablished as Cambodia’s official state religion. However, the impact from Khmer Rouge times is still strongly felt. After the loss of so many leaders, some communities have struggled to teach and ordain new monks.

2 The Killing Fields

Two of the biggest tourist sites in Cambodia are Angkor Wat, the famous temple complex built by the medieval Khmer Empire, and Choeung Ek, the country’s most infamous killing field. One of thousands of mass graves from Khmer Rouge times, Choeung Ek contains the remains of more than 8,000 people who were executed there. A Buddhist stupa on the site holds thousands of human skulls. Most victims, including children, were tortured before they were killed. They were forced to dig their own graves and were often hacked or beaten to death with axes, knives, and bamboo sticks because the Khmer Rouge didn’t want to waste bullets. Sometimes, small children and babies were smashed against trees until they died. After being attacked, victims were pushed into the graves they had dug, and dirt was thrown over them. Some people survived the torture and were buried alive. In 2015, there are still killing fields that have yet to be excavated. It’s also possible that many more killing fields will be discovered in the future. Due to the shallowness of the graves, old bones and teeth sometimes turn up around the country after a heavy rainfall.

1 Western Support For The Khmer Rouge

When the Khmer Rouge seized power in 1975, a handful of Western intellectuals and antiwar activists hailed them as liberators. These supporters had harshly criticized the previous, American-backed Lon Nol regime and the deadly bombing campaigns that the US had carried out in Cambodia during the Vietnam War. Now they hoped that the Khmer Rouge would disprove Western fears that a Southeast Asian country ruled by communists would be a disaster. Even as refugee stories started leaking out of Cambodia, these intellectuals downplayed Khmer Rouge atrocities and charged that refugee reports were exaggerated or false. In May 1977, the US Congress launched an investigation into the Cambodian crisis at the urging of Representative Stephen Solarz, who had talked to refugees in Thailand. “In its own way,” Solarz said at a Congressional hearing, “the indifference of the world to events in Cambodia is almost as appalling as what has happened there itself.” However, scholars like David Chandler and Gareth Porter countered that it was hypocritical to condemn the Khmer Rouge without criticizing previous American military policy in the region. They argued that the death toll couldn’t have been higher than the thousands, and that while the Khmer Rouge wasn’t perfect, the regime it had overthrown was much worse. In Porter’s book Cambodia: Starvation and Revolution, which was reviewed favorably by Noam Chomsky, Porter and his coauthor George Hildebrand denied the existence of mass starvation in the country and neglected to mention the public executions and abuses committed against Cambodian minorities. After Vietnam overthrew the Khmer Rouge in 1979, Pol Pot and his followers fled to Thailand, where they waged a guerrilla war against the new, Vietnamese-backed Cambodian government. Instead of calling for Pol Pot’s capture, big powers like the US and China supported his efforts with millions of dollars in military aid. With Vietnam supported by the Soviet Union, the West chose to recognize the Khmer Rouge as the legitimate Cambodian government. Until pressure to prosecute the leaders of the Khmer Rouge escalated in the 1990s, the Khmer Rouge held the Cambodian seat in the United Nations as part of an anti-Vietnamese coalition until 1991. Although many Khmer Rouge leaders have since been brought to justice for their crimes, Pol Pot was never prosecuted, having died in 1998. Tristan Shaw runs a blog, Bizarre and Grotesque, where he writes about unsolved murders, paranormal phenomena, and other creepy things. You can also find him on Hubpages, where he’s recently started composing lists about weird historical subjects.