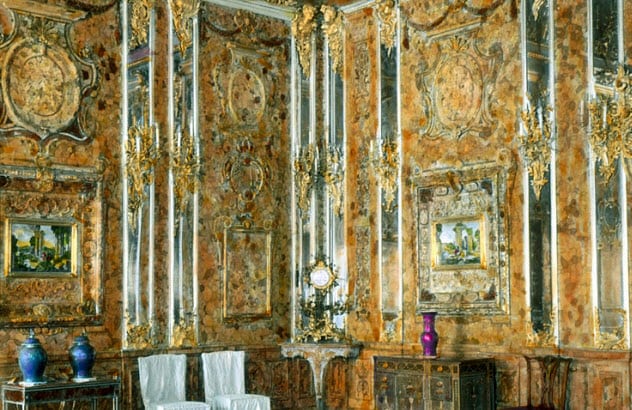

Construction of the opulent “Eighth Wonder of the World” began at the command of the king of Prussia in 1701. Although estimates of its size vary, the Amber Room was believed to span about 55 square meters (592 ft2) after 18th-century renovations. It contained over six tons of amber backed by glittering gold and set with diamonds, rubies, and emeralds. As a peace symbol between allies, the Amber Room was moved from its place in Charlottenburg Palace twice—once to Winter House in St. Petersburg and then to Catherine Palace in Pushkin. As an act of war, the room was moved once more before being lost forever. In 1941, invading Nazi soldiers tore down the room, packed its panels into 27 crates, and shipped it to Konigsberg (now Kaliningrad), Germany. When the city was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1943, the room went missing. In subsequent years, governments, historians, archaeologists, bounty hunters, and treasure seekers alike have sought it out, interviewing thousands of witnesses, poring over records, digging up locations all over Europe, and spending fortunes along the way. As of this writing, the room has never been found.

10 Unmoved From Kaliningrad, Germany

Although the prominent theory holds that the Amber Room must have been destroyed by the bombs which rained down upon the city then called Konigsberg, some evidence contradicts this. In over 1,000 pages of reports compiled by the decade-long Soviet investigation, no witnesses attest to any unusual odors as the city burned. Officers involved in this investigation believed that it would be impossible to miss the equivalent of 6 tons of incense burning at once. In 1997, a German raid in Bremen lent credence to the idea that the room had survived the bombing.[1] One of its Florentine mosaic panels turned up for auction. After its seizure, the panel was authenticated but the seller claimed ignorance as to its origin. His father, a deceased Wehrmacht soldier, never shared the secret of the panel, not even with his own flesh and blood.

9 Hidden In A Silver Mine On The Czech Border

Helmut Gaensel was a bounty hunter. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the bounty he hunted was the bejeweled panels of the Amber Room. Former SS officers living in Brazil had tipped him off to a location. According to them, the panels were deposited in the 800-year-old Nicolai Stollen mine near the border between Germany and the Czech Republic. Gaensel was not the only man to hear the tale. While he and a team of engineers, mining experts, and historians attempted to dig into the mine from the German side, a rival group led by Peter Haustein, then mayor of the town of Deutschneudorf, tried burrowing in from the Czech side. Though the competition led to international headlines and legal headaches, neither team proved successful.[2]

8 Covered In A Murky Lagoon

The mayor of the Lithuanian town of Neringa believed that the Amber Room was hidden beneath the dirty waters of a nearby lagoon. According to Stasys Mikelis, SS soldiers were seen attempting to hide wooden crates in the shoreline near the end of the war. They did not count on rising sea levels to submerge their loot.[3] Not only did Mikelis believe it, he assembled a research team in 1998 to find it, hoping to put his town on the map. His dream was not realized.

7 Lost In A Bavarian Woodland

Georg Stein was a strawberry farmer and an avid treasure hunter. His heart was set on finding the Amber Room, but he got too close according to some sources. Stein claimed to have discovered a secret radio frequency and to have listened to the last-known communication about the transfer of the Amber Room. This message was reportedly sent from the Castle Lauenstein on the border of Thuringia on a direct shortwave to Switzerland. Stein then arranged to meet a “search competitor” in Bavaria. The meeting was not to be. In 1987, Stein was found dead in the woodland.[4] His body was stripped, his stomach slashed open with a scalpel. The death was ruled a suicide.

6 Beneath Wuppertal, Western Germany

Pensioner Karl-Heinz Kleine believes that he knows the location of the Amber Room and who hid it there. According to Kleine, the Nazi’s chief administrator in East Prussia, Erich Koch, secreted the treasure in his hometown of Wuppertal in the industrial Ruhr area.[5] It would not be a far stretch to imagine it of Koch. Even the Nazis were appalled by his brazen thefts and use of concentration camp inmates for personal gain. Koch was tried for corruption before a Nazi court in 1944 and sentenced to death. Later reprieved, he returned to favor and continued amassing his personal fortune until the end of the war. Once captured in Poland, he was sentenced to death for the murder of 72,000 Poles and for sending another 200,000 to labor camps. But he escaped his sentence yet again. Koch’s ill health prevented Poland from carrying out his death sentence, and he lived in prison for 27 years, unrepentant to the last.

5 Shipwrecked In The Baltic Sea

The sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff on the night of January 30, 1945, was the worst disaster in maritime history. Under the press of the Red Army and rumored defeat, a great evacuation of German civilians began on the Baltic Sea. Every seaworthy vessel was placed into service. So it was that the Wilhelm Gustloff, a luxury liner designed for fewer than 2,000 people, carried 10,582 shivering evacuees on that fateful night. It was flanked by only one military escort, which stood no chance when a Soviet submarine fired three torpedoes at the Gustloff. Each torpedo hit its target. An estimated 9,343 people died that night, half of them children. The exact location of the Gustloff has long been known and searched. But some still claim that it may contain the hidden remains of the Amber Room. As the wreckage of the Gustloff is recognized as a war grave, diving to it, penetrating it, or both is illegal. But a lack of resources has left Polish authorities unable to protect it.[6]

4 Aboard A Ghost Train, Walbrzych, Southwest Poland

It has long been said that a Nazi train loaded with treasure was lost in secret tunnels under a mountain in Walbrzych. Nobody knows the name of the train, its mission, or from where its precious cargo came. Some speculate that the lack of written evidence of the train strengthens their hypothesis. Secrecy, the theory goes, was more important than paperwork, even to the Germans. Some theorize that the train may have carried the stolen wedding bands and other personal jewels of interned Jews, while others insist that the train bore the crated panels of the Amber Room.[7] In 2015, two men, a German and a Pole, claimed to have found the train. The local government of Walbrzych refused to comment on the matter except to warn that the train may be booby-trapped by mines if it exists.

3 In a Bunker In Mamerki, Northeastern Poland

In 2016, officials of the Mamerki Museum reported to have found a hidden room inside a World War II–era bunker using geo-radar. Bartlomiej Plebanczyk of the museum believed it possible that the panels of the Amber Room were hidden inside. His theory was based upon the testimony of a turncoat Nazi soldier. In the 1950s, the former Nazi told Polish soldiers that he had witnessed heavily guarded cargo trucks delivering their load to the bunker in winter 1944.[8]

2 Buried In Tunnels Under The Ore Mountains In Eastern Germany

In 2017, treasure hunters Leonhard Blume, Peter Lohr, and Gunter Eckhardt claimed to have deduced the location of the room via archival and radar sleuthing. Both the East German and Russian secret police held years-long searches for the Amber Room. It is from their records that these men reportedly found a clue as to the room’s whereabouts. Eyewitnesses claimed that a shipment of crates had been hidden inside the tunnels. The entrance to the tunnels, they said, was then blown up. Blume, Lohr, and Eckhardt eagerly surveyed the “Prince’s Cave” near the Czech border, and the results were astounding. Mr. Blume said, “We discovered a very big, deep, and long tunnel system and we detected something that we think could be a booby trap.” Their search continues.[9]

1 A Secret Russian Location Known By Stalin

The impending raid of Winter Palace was known to the officials and curators of Catherine Palace. According to the official record, they attempted to disassemble and hide the Amber Room. When the brittle panels began to crumble, they chose to wallpaper over them instead. But they could not outwit the Nazis, who discovered the trick almost at once. This conspiracy theory holds that Joseph Stalin fooled the soldiers after all. The panels they stole were replicas, while the real Amber Room had already been shipped off and hidden elsewhere. If true, the Amber Room may have been cleverly saved, only to be lost forever.[10] Olene Quinn is the historical fiction author of The Gates of Nottingham and Prince Dead. A self-described armchair historian, she resides in Northern California.