10George Freeman

In the 1980s, the US was overtaken by the Satanic Panic, a widespread and almost entirely unfounded belief that large numbers of Americans were secretly worshiping Satan and committing horrifying ritualistic acts in his name. The most infamous example of this moral panic was the McMartin Preschool Trial. Ray Buckey, the son of McMartin Preschool owner Peggy, was initially accused by a parent of abusing her child, apparently as part of a strange ritual. The parent in question was subsequently diagnosed with schizophrenia, but the allegations quickly spiraled out of control and the Buckeys and other McMartin teachers were arrested and indicted for subjecting the children under their care to Satanic ritual abuse. To prove their case, prosecutors relied on the testimony of the children in question, who the defense alleged were coaxed into saying what the prosecution wanted to hear. The stories the child witnesses came up with were frankly unbelievable, involving a network of secret underground tunnels, animal sacrifices in a church, and being taken to cemeteries to dig up coffins. As horrified parents began digging up the school in a futile hunt for the supposed tunnel network, prosecutors pressed on with the trial. The only adult witness to testify against the Buckeys was George Freeman, a convicted criminal and cellmate of Ray Buckey. Freeman told the court that Buckey had admitted that he was a child molester, a member of a secret cult, and a key figure in an international child pornography ring. The defense was quick to pounce on Freeman’s testimony, accusing him of lying under oath and pointing out that Freeman had perjured himself in a previous trial and that the district attorney was paying his living expenses. In fact, the prosecution was eventually forced to admit that Freeman had perjured himself again in a preliminary hearing for the McMartin trial. In order to avoid a mistrial, the judge sided with the prosecution and granted Freeman immunity from prosecution over the perjury incident. Nonetheless, the incident finished Freeman as a witness in the case, since he had essentially admitted to lying in exchange for favorable treatment from the DA’s office. He insisted he only did this out of concern for his mother and sister, prompting the examining attorney to acidly inquire if he meant the same mother and sister he had previously been arrested for tying up and robbing. Peggy Buckey was eventually acquitted and two juries deadlocked over Ray Buckey’s guilt or innocence. The prosecution declined to try him a third time, and he was released after five years in jail. Soon after he testified against Ray Buckey, George Freeman was arrested again, this time for robbing a woman at gunpoint.

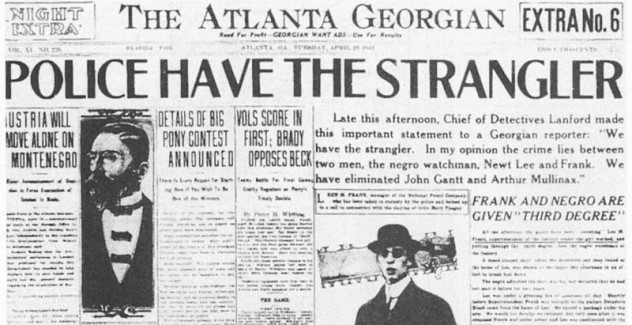

9Jim Conley

The trial of Leo Frank was one of the most famous American court cases of the early 20th century. Frank was a factory supervisor from Atlanta, Georgia, and a leader in Atlanta’s growing Jewish community. But on April 26, 1913, his life was turned upside down when a young girl named Mary Phagan was found bludgeoned to death in his factory. Phagan was a former employee of the factory and had apparently gone to collect her last paycheck. Despite a lack of evidence, Frank was charged with the crime and a media circus quickly developed. Bizarrely, the prosecution’s case revolved around a janitor at the factory named Jim Conley, who was almost certainly involved in Mary Phagan’s murder. In fact, he had been seen near the crime scene at the time of the murder and was subsequently caught rinsing out a shirt soiled with blood. Investigators also believed he was the author of the notes found near Phagan’s body. Despite this, prosecutors decided Frank was the perpetrator and struck a deal with Conley to testify. Conley told the court that he was acting as a lookout while Frank “chatted” with Phagan, only to discover that Frank had killed Phagan for refusing his advances. Frank then ordered Conley to help him move the body and to write the notes. Despite inconsistencies in Conley’s testimony, Frank was sentenced to hang. One person not entirely convinced of Frank’s guilt was Georgia governor John Slaton, who commuted his sentence to life in prison. In an atmosphere rife with anti-Semitism, this act of clemency infuriated many people. On August 16, 1915, an angry mob broke into Frank’s jail cell and lynched him. Jim Conley didn’t completely escape punishment for his role in the murder, receiving a light sentence of one year in jail. He died in 1962. Twenty years later, a local named Alonzo Mann gave a shocking deathbed confession: As a 13-year-old factory worker, he had seen Conley carrying Phagan’s body alone, meaning Conley had lied when he claimed to have helped Frank move the body. Mann had stayed quiet because Conley threatened his life if he ever told.

8Marvella Brown

In 1983, a 58-year-old jewelry store owner named Isadore Rozeman was shot dead during a robbery in Shreveport, Louisiana. Police identified four suspects in the case, but only one, Glenn Ford, went to trial. Ford had known Rozeman and had been seen in the vicinity of the store on the day of the robbery. Police had also caught Ford trying to pawn some of the stolen jewelry, although he claimed it had been given to him by someone else. With a lack of forensic evidence—the murder weapon never turned up—the trial largely hinged on the testimony of a woman named Marvella Brown. She claimed to have been with Ford prior to the robbery and seen him carrying the gun. The details of Brown’s testimony didn’t stand up to scrutiny and she actually broke down during cross-examination and admitted she had lied, apparently at the behest of detectives investigating the case. In her defense, she explained she had been shot in the head years earlier, which had affected her ability to think. Despite this and other exonerating evidence, the jury still found Ford guilty. He was sentenced to death. While he waited for his sentence to be carried out, Ford was held in the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, spending most of his time in solitary confinement. Thirty years later, he was released from prison after evidence emerged that local detectives had lied on the stand and concealed evidence implicating only Henry Robinson and his brother Jake, Marvella Brown’s boyfriend at the time.

7Allen Hall

In the early 1970s, racial tensions threatened to engulf Wilmington, North Carolina. Many African Americans were angry about the slow pace of integration in the town, and violence erupted in February 1971, with clashes between African Americans and the KKK culminating in the firebombing of a white-owned grocery store. Ten African Americans were charged with the bombing and sentenced to long prison terms. A popular cause among civil rights activists, they became known as the Wilmington 10. A key part of the prosecution’s case was the testimony of a man named Allen Hall, who was supposedly an eyewitness to the alleged crime. Hall was a convicted felon who told the prosecutor that he could help convict the Wilmington 10 if the prosecutor helped him in return. So, in exchange for his testimony, Hall was removed from prison and allowed to stay with his girlfriend in a beach house. Hall was such a dedicated witness that he even physically assaulted the defense lawyer during his cross-examination. Years later, Hall decided to come clean and admitted his testimony was false. Two other prosecution witnesses then came forward to say the same thing. But it was not until a few years later that most of the Wilmington 10 were even paroled. It took even longer for the state to admit that their convictions were wrong in the first place.

6Captain Ernest Medina

On March 16, 1968, American soldiers under the command of Lieutenant William Calley entered the Vietnamese village of My Lai. Ostensibly on a “search and destroy” mission, the soldiers tore through the village, massacring hundreds of men, women, and children in the most brutal ways imaginable. In the aftermath of the My Lai massacre, murder charges were brought up against Lieutenant Calley. In his defense, Calley argued that he was acting under orders from his superior, Captain Ernest Medina. But prosecutors couldn’t present any evidence that Medina had ordered the killings or had been there when they had occurred. During his own court martial, Medina denied even knowing anything about My Lai until a year later. Major William Eckhart, the prosecutor, felt Medina was lying about his ignorance of the massacre. But he couldn’t prove it. While Calley was found guilty, Captain Medina was acquitted. He resigned from the military soon afterward. A few years later, Medina was called to testify at the trial of his brigade commander, Colonel Oran Henderson. This time he shocked everyone by admitting that he had lied. In fact, he had known about the massacre on the day it occurred. But since he was no longer in the military, he couldn’t be court-martialed for perjury and avoided any legal punishment.

5Henry Cook

Thanks to Henry Cook, Clarence Earl Gideon is one of the most famous drifters who ever lived. On a hot Florida morning in the summer of 1963, someone broke into a pool hall and stole some money and alcohol. Henry Cook came forward as a witness and told investigators that he had witnessed Gideon committing the crime. The police accepted Cook’s story without bothering to ask why he would be hanging around a pool hall at 5:30 in the morning. Unable to afford a lawyer, Gideon was forced to represent himself. In a trial that lasted just one day, Gideon was sentenced to five years in prison. While in prison, Gideon sat down and did something that was almost unprecedented: He wrote a letter to the Supreme Court of the United States, claiming that his right to a fair trial had been violated because he couldn’t afford a lawyer. Even more surprisingly, the court listened. The resulting decision, Gideon vs. Wainwright, established that everyone charged with a felony is entitled to legal representation. Gideon was granted a second trial. This time, he had a lawyer, who quickly demolished Cook’s testimony and strongly implied that Cook was the actual thief, although he never faced charges. Gideon was set free, although by then people were more interested in the groundbreaking new legal precedent.

4Sam Hadaway

Clarence Earl Gideon was only an acquaintance to Henry Cook, but Sammy Hadaway’s lies put his own best friend behind bars. In 1995, police in Milwaukee were investigating the rape and murder of 16-year-old runaway Jessica Payne. Detectives were having trouble with the investigation until they interviewed Sam Hadaway. Believing that the police were zeroing in on him as a suspect, Hadaway fingered his friend, Chaunte Ott. According to Hadaway, Ott had raped and murdered Payne, while Hadaway’s involvement in the crime extended only to robbing her. Based on this testimony, Ott was given life in prison, while Hadaway was sentenced to five years. Then things got weird. The police finally ran a DNA test and were surprised to discover that the result implicated someone else entirely: a convicted serial killer named Walter Ellis. Bizarrely, investigators knew Ellis had been killing women in the area at the time, but somehow managed to overlook him as a suspect until the DNA test. Instead, they went after Ott on the basis of his friend’s false testimony. Ott and Hadaway have both since been released from jail. Hadaway no longer speaks to his former friend, and says he regrets lying on the witness stand, even if he did it to protect himself.

3Mel Ignatow

Mel Ignatow was a violent criminal who more or less got away with murder. In 1988, Ignatow lived in Louisville, Kentucky, and was dating a woman named Brenda Schaefer. When he found out that Schaefer was planning on breaking up with him, he recruited his ex-girlfriend, Mary Shore, to help him abduct and murder her. With Shore’s assistance, Ignatow tortured, raped, and photographed Schaefer before killing her. Police immediately suspected Ignatow, but lacked evidence or even a dead body. Playing to Ignatow’s vanity, they were able to persuade him to voluntarily appear in front of a grand jury, where he denied having anything to do with Schaefer’s disappearance but did mention Shore’s name, prompting the state to call her as a witness. In a dramatic courtroom scene, Shore insisted that she had only ever met Schaefer once, but then accidentally mentioned “the last time I saw her.” It was a minor slip, but when the prosecutor brought it to her attention she fled the court in tears and subsequently confessed everything. It seemed like the breakthrough the case needed, but Ignatow’s lawyers were able to cast doubt on the testimony, suggesting that Shore had killed Schaefer out of jealousy. With no other compelling evidence, Ignatow was acquitted of the murder of Brenda Schaefer. Just a few months later, the smoking gun turn up when a contractor working on Ignatow’s house found photographs taken during the murder. But the state was unable to prosecute Ignatow again due to double jeopardy. So Ignatow got away with murder—almost. Although the state couldn’t prosecute him for the murder, they could prosecute him for perjuring himself during the trial. And they did, relentlessly, securing sentences of five years in federal prison followed by nine years in state prison, which largely kept Ignatow off the streets until shortly before his death in 2008.

2Lorenzo Nesi

From 1968 until the mid-’80s, the picturesque Italian city of Florence was gripped by the crimes of an unidentified killer known as the Monster of Florence, who has never been caught and might actually be more than one killer. The Monster seemed to stalk the hills outside the town, targeting young couples who had parked there at night for some privacy. On three separate occasions, investigators arrested a suspect, all members of the same Sardinian clan, only for the Monster to strike again while the suspect was in custody. As a result, the investigation dragged on for years, growing more and more complicated. In the 1990s, police focused on a new suspect, an elderly farmer named Pietro Pacciani. The evidence against Pacciani was thin, including a single bullet that may or may not have fit the gun used by the Monster. But Pacciani was an extremely unsympathetic character with a long history of violence, including raping his own daughters. And the prosecution’s case was immensely strengthened by the appearance of a witness named Lorenzo Nesi, who claimed to have seen Pacciani on the night of one of the killings. According to author Douglas Preston, who has studied the Monster killings, Pacciani was almost certainly innocent. According to Preston, Nesi was an attention seeker who got basic facts about the case wrong, including the color of Pacciani’s car. He also displayed a tendency to suddenly recall new facts when it was convenient and claimed that roadworks had forced him to travel past the crime scene, even though no roadworks were taking place that night. Thanks in part to Nesi’s testimony, Pacciani was found guilty, but the conviction was overturned after the evidence of his innocence became so overwhelming that one of the prosecutors actually became an advocate for him.

1Big Tobacco

In April 1994, the United States House of Representatives conducted an investigation into tobacco products. For over six hours, Congressmen grilled executives from seven different tobacco firms, including big names like R.J. Reynolds, Philip Morris, and the American Tobacco Company. The senators wanted to understand the health risks of cigarettes and their links to heart disease, lung disease, emphysema, and other diseases. The Congressmen were well prepared, armed with scientific evidence and prepared to point out errors made in the reports submitted by the tobacco companies. At one point in the hearing, Representative Henry A. Waxman asked Andrew Tisch, the CEO of Lorillard Tobacco Company, whether cigarettes cause cancer. Tisch’s answer was, “I do not believe that.” Executives of the other tobacco companies gave similar answers, insisting that they “did not believe” that nicotine was addictive. Based on these statements, the US Department of Justice seriously considered leveling perjury charges against the executives. The evidence that cigarettes are addictive and cause cancer is overwhelming. Ultimately, they were unable to bring charges because of the word “believe.” If the executives had simply said no, they would have been guilty of lying to the senators.