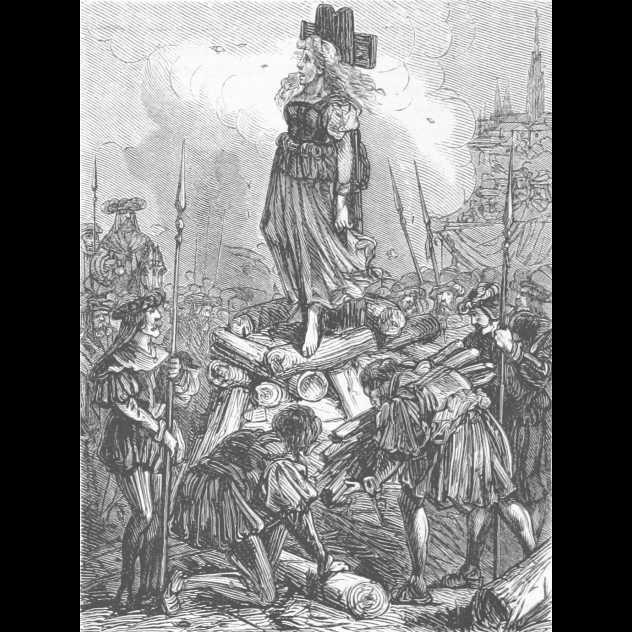

10 Georg Scherer

Vienna is not the first place that springs to mind when talking about witches, and there’s a good reason for that: There has only been one case of witch burning in the city’s history—the so-called Plainacher Witch Affair of 1583. The alleged witch was 70-year-old Elisabeth “Elsa” Plainacher (pictured above), who raised her granddaughter Anna in Mank, Lower Austria. When Anna came of age, she left her grandmother and started to experience seizures, most likely due to undiagnosed epilepsy. In came Georg Scherer, a charismatic but completely fanatical Catholic pulpit orator who was a firm believer in putting witches to death. He quickly determined that Anna was the victim of a hex, and after a thorough “investigation,” concluded that her grandmother Elsa was to blame. (In Scherer’s eyes, it didn’t help that Elsa was a Lutheran.) After a long “interrogation,” Anna was finally convinced that her grandmother was indeed the culprit behind her hexing, and the “witch” was brought in for some “interrogation,” herself. Unsurprisingly, after long bouts of torture, Elsa finally confessed to being a witch and was sentenced to death. Scherer’s extracted confession seems to have been unreliable even for those times, and the Mayor of Vienna pleaded with the emperor to stop the execution. However, it was not enough to overcome Scherer’s ecclesiastical influence, and Elsa Plainacher was burned at the stake on September 28, 1583.

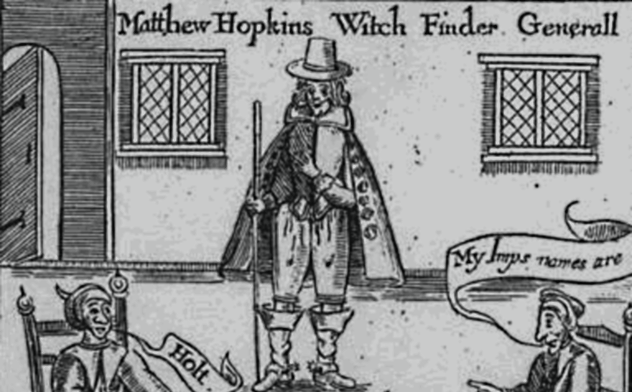

9 Matthew Hopkins

In the world of witch-hunters, Matthew Hopkins was the big, bad dog. As many as 200 cases of witchcraft are credited to Hopkins or his followers. Although notorious in his time, little is known of Hopkins before he became witch finder general, a title that he gave himself. It would appear that Hopkins was born during the 1620s and practiced as an unsuccessful lawyer before he realized that witch-hunting provided him with an extra revenue source. It is likely that Hopkins undertook witch-hunting for money rather than out of fanatical belief. England’s laws on dealing with witches were a bit more relaxed than in continental Europe, but they still bordered on torture. Hopkins often employed sleep deprivation as a way of preventing witches from summoning familiars. He would also force them to walk all night in order to tire them out and make them confess. In certain cases, Hopkins relied on ducking, a practice in which the alleged witch was bound and dunked in water. The “reasoning” behind this was that witches have denied their baptism and would be repelled by water and float. If they weren’t witches, they would sink, drown, and go to Heaven. If they were, they would float and would be executed for witchcraft. Hopkins’s late life was mostly undocumented. Eventually, the clergy had enough of his overzealous nature, and his influence diminished considerably. One pleasing story says that Hopkins was himself accused of being a witch and had to undergo his own ducking challenge.

8 Sebastian Michaelis

Sebastian Michaelis was a grand inquisitor with the French Inquisition during the late 16th to early 17th centuries. He is mostly remembered today for writing a book called The Admirable History of Possession and Conversion of a Penitent Woman in 1612. Among other things, the book features a hierarchy of devils that is still commonly referenced today. It places Lucifer at the top, followed by Beelzebub, Leviathan, and Asmodeus. What made Michaelis’s hierarchy particularly interesting was that he obtained the information firsthand from the devils during an infamous case of demonic possession. The year was 1611, the peak of witch-hunting in France. The small town of Aix-en-Provence was shocked by multiple cases of Ursuline nuns being possessed by demons. The local clergy sent for help from Michaelis who, by this time, was already a feared grand inquisitor who had sent 18 witches to their deaths. It all started with a young nun named Madeleine de Demandolx de la Palud. She claimed to be possessed by demons and blamed a local priest named Father Gaufridi. She accused the priest of making a pact with the Devil and engaging in sexual perversions with her while she was possessed. Before long, several other nuns decided that they were also possessed by demons. Michaelis ordered the nuns exorcised and accused Gaufridi of witchcraft. When no physical evidence was found implicating Gaufridi, Michaelis accepted the testimony of the “possessed” witches, which was unprecedented in France at the time. Gaufridi was burned at the stake.

7 Pierre De Lancre

Pierre de Lancre was pretty much a worst-case scenario of what can happen when a witch-hunting fanatic has too much power. In 1609, the province of Labourd in France saw more than its fair share of witchcraft accusations, which occasionally led to violence. This was likely caused by the clash of cultures between the Basque, Spanish, and French people who all resided in the area. King Henry IV elected the judge of Bordeaux to deal with the situation. That judge was Pierre de Lancre, and he wasted no time in dealing with the scores of witches infesting the area. Being named by the king himself, Lancre had a lot of power and used it to its fullest. Although he only spent four months in the region of Labourd, Lancre executed dozens of people for witchcraft, with some sources putting the number as high as 80. That number was mere peanuts to Lancre, who estimated that thousands more witches were active in the area. If he had his way, he would have burned them all at the stake. Fortunately, others were able to see how bloodthirsty Lancre was, and he was eventually dismissed from office. Afterward, he wrote three books on the subject, in which he presented what he considered to be signs of witchcraft. Included, among others, were dancing indecently, swearing, eating too much, and keeping toads and lizards.

6 Balthasar Von Dernbach

Balthasar von Dernbach was a 16th-century Benedictine monk who spent most of his life at the Fulda monastery, also serving as its prince-abbot. He was sent to the monastery at age 12 and slowly rose through the ranks until he became successor to the current prince-abbot, who also happened to be his uncle. Right from the beginning, Balthasar instituted a stern policy of counterreformation against Protestantism, forcing his subjects to return to the Catholic faith. His actions proved unpopular enough that a revolt forced him to abdicate. After more than 25 years, Dernbach was reinstated to his position in 1602. This time, he focused his anger on witches, triggering one of the largest witch trials in history. One of the victims was Merga Bien, a German heiress who was forced to confess to being pregnant with the Devil’s child and to killing her first husband. She was among the first to be convicted and burned at the stake for witchcraft, but over 200 more would follow her in the years to come. Dernbach enlisted the help of Balthasar Nuss to preside over the witch trials, as they seemed to share the same fanatical hatred. After Dernbach’s death in 1605, it didn’t take long for the trials to end. It was concluded that his follower, Balthasar Nuss, was merely using the trials as an excuse to gain power and money, so he was jailed and eventually beheaded.

5 Peter Binsfeld

Peter Binsfeld was a very influential 16th-century German theologian who would come to be regarded as one of the premiere experts on witchcraft. He served as auxiliary bishop of Trier and worked under Archbishop Johann von Schonenberg during the infamous Trier witch trials from 1587–93. This gave him a fierce reputation as a witch-hunter but also inspired him to write on the subject of witchcraft based on his experiences in Trier. His book, Treatise on the Confessions of Evildoers and Witches, became very popular and was widely circulated throughout Europe. It could be argued that the book did a lot more harm to people accused of witchcraft than witch trials ever could, due to its widespread influence. Binsfeld felt that people were too lenient when it came to dealing with witches and that witchcraft was crimen exceptum, which excused it from standard investigation methods. He was completely in favor of torture and, in fact, considered regular techniques to be underwhelming. Binsfeld deemed that one credible accusation of witchcraft was enough to begin torture and that it was perfectly acceptable to torture children. He also actively encouraged people to accuse family members as, by doing so, they were saving their souls. Not everyone was onboard with Binsfeld’s extreme views, but there was little that they could do about it. Any dissenters were quickly denounced as heretical. One scholar from Trier named Cornelius Loos, who wrote against Binsfeld’s teachings, had his books confiscated and was imprisoned.

4 Nicholas Remy

If he is to be believed, then Nicholas Remy is the most prolific witch-hunter in history. This 16th-century French magistrate claimed to have been involved in convicting and executing over 900 witches. However, while it is certain that Remy gained a reputation as a fearsome and unforgiving witch-hunter, there is insufficient evidence to corroborate such a high number, since court records have not survived. Remy himself was only able to provide detailed accounts for 128 people, which seems like a far more likely number. Originally, Remy worked as a lawyer with a side job as a historian. Allegedly, his eagerness to deal with witchcraft came after the death of his eldest son. Remy blamed the death on a local beggar who Remy thought placed a curse on him. His fervor and passion for the work he did were often rewarded, as Remy climbed the social ladder and gained more and more power. In 1583, he was made a noble, and in 1591, he was named the procureur-general for the duchy of Lorraine. When Remy wasn’t busy hunting witches, he was writing about witches. His book Demonolatry was published in 1595 and became the most popular text on witch-hunting throughout many parts of Europe. Among his many claims, Remy asserted that witchcraft usually ran in the family, which meant that having parents accused of the crime was a sure sign that their child was also a witch. Remy advocated for eliminating these bloodlines completely.

3 Alonso De Salazar Frias

Alonso de Salazar Frias is a strange case among witch-hunters. He was known as the Witches’ Advocate, even though he was among the Spanish inquisitors involved in the largest witch hunt in history, which took place in Navarre during the early 17th century. He was different because even though he believed in witchcraft and punishing witches, he didn’t think that witches necessarily needed to be executed. Salazar’s witch hunt occurred shortly after that of Pierre de Lancre’s in France. In fact, it was that event which generated mass hysteria in Spain, particularly in a few towns in Navarre. The increasing number of accusations and confessions led people to believe that there was a massive witch cult operating in the Basque region. An Inquisition tribunal was assigned to investigate the case, and Salazar was among the three members. The other two inquisitors were like you would expect; everyone who looked at them funny was a witch and needed to be put to death. However, Salazar had trouble believing that the scale of this supposed coven could possibly be real. His notes included over 7,000 people who had been denounced or confessed to be witches. Salazar successfully campaigned for some never-before-seen methods in witch-hunting. For starters, children’s confessions were eliminated outright. He also concluded that, besides accusations and confessions, there was insufficient evidence to convict most of the people implicated of witchcraft. In the end, only 31 people were convicted, and 11 or 12 were burned at the stake.

2 Roger Nowell

Although it’s not as famous, Pendle Hill is sometimes referred to as the “Salem of England” because one of the most famous witch trials in English history occurred there in 1612. The trial not only resulted in the execution of 10 people, but also set a dangerous precedent in witchcraft cases that would go on to have a lasting influence, including during the Salem witch trials. Before this case, children under the age of 14 were considered unreliable witnesses, and their testimonies were not allowed in court. However, convictions in this case were secured using the testimony of a nine-year-old girl named Jennet Device. This would not have been possible if King James I hadn’t suspended normal evidence rules for witch trials because he had a keen interest in witch-hunting. Roger Nowell was the local magistrate in the area, and he heard about a dead merchant who was allegedly cursed by a witch for not selling her pins. He knew that the king hated witches and wasn’t keen on Catholics, either. The alleged witch, named Demdike, was both. Nowell’s ambition made him realize that prosecuting this case was a good way of earning favor with King James. Nowell used Jennet Device’s testimony and convicted 11 people of witchcraft, including Jennet’s family members. Ten of them were either executed or died in prison, and the whole event was covered by court clerk Thomas Potts in a book called The Wonderful Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster.

1 Johann Von Schonenberg

Already mentioned as the mentor of Peter Binsfeld, Johann von Schonenberg was the archbishop responsible for the biggest witch trial in European history. Back in the late 16th century, the region surrounding the German city of Trier was having frequent problems involving sterility. With no obvious culprit, attention soon turned toward witchcraft. This led to a witch trial that was unparalleled in scope at the time. Each town and village within the diocese of Trier was scoured for any sign of witchcraft. Nobody was safe from accusation. Judges, priests, councilors, and deans were all taken to trial. Those who weren’t executed had their goods confiscated and were exiled, as were the children of the convicted. The trials would last for over a decade, from 1581–93. In the city of Trier alone, 368 people were executed, along with scores of unrecorded deaths throughout the diocese. And it was all the work of one man—Johann von Schonenberg. Schonenberg was the archbishop-elector of Trier. During the Middle Ages, being a member of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire was a position of great power, and Schonenberg used it. Those who opposed him were quickly arrested, persecuted, and usually killed. This was all part of his plan to purge his land of undesirables which, in his case, included witches, Jews, and Protestants. The witch trials finally ended in 1593. By then, the population of Trier was an impoverished, diminished shell of its former self. Radu is a history/science buff with an interest in all things bizarre and obscure. Share the knowledge on Twitter or check out his website.