When hurricanes break through the coastline and wreak havoc on people’s lives, human nature also gets uncovered. Sometimes, people don’t react exactly how you’d expect—and some of the facts around these disasters aren’t at all what you’d imagine.

10 Walmart Customers Stock Up On Pop-Tarts And Beer

When Hurricane Frances was about to hit Florida, Walmart jumped into action. They had mountains of data on their customers and on every aspect of their lives. With thousands in jeopardy, Walmart knew they had a responsibility: They had to figure out how to make a quick buck from it. They looked through their data to predict customer behavior and discovered that their customers have a strange reaction when a storm is about to hit. Instead of water or flashlights, the biggest things people stocked up on were beer and strawberry-flavored Pop-Tarts. The difference is huge. Before a hurricane hits, beer becomes Walmart’s top-selling item and Pop-Tart sales go up 700 percent. People grab Pop-Tarts and beer before a disaster so often that Walmart has actually started sending out extra truckloads of stale breakfast pastries to make up for the demand. This isn’t a natural human instinct. It only happens to US Walmart customers. When Costco did a study on their customers in Hawaii, they found that beer sales actually plummeted.[1] At Costco, people stocked up on water and batteries instead to make sure that their families could survive. But not at Walmart. When death stares them in the face, Walmart customers grab a cold Pop-Tart and lukewarm beer, sit back, cross their fingers for luck, and enjoy the ride.

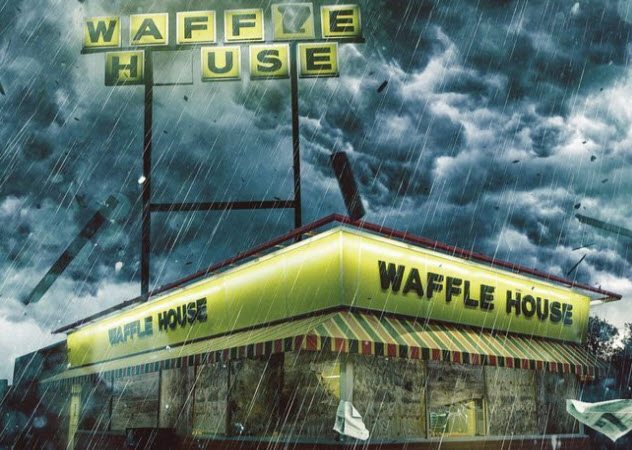

9 FEMA Uses Waffle Houses To Measure Disaster Recovery

FEMA has a strange way of checking how the nation’s disaster recovery is going. When they can’t get clear information, they don’t necessarily bother sending in a team to check how a community’s doing. They just call the local Waffle House. Believe it or not, this is actually FEMA’s standard system now. Waffle Houses almost exclusively operate in hurricane areas, and they’re uniquely willing to make their minimum-wage employees endanger their lives by working through a storm with the power of a generator. So, ever since 2012, FEMA has been paying Waffle House to report the status of their stores to the agency directly.[2] There’s a three-tier system for measuring if an area has recovered. Areas are marked “green” if the local Waffle House is fully open, “yellow” if they’re working off a limited menu, and “red” if the area is so dangerous that even Waffle House isn’t willing to risk its employees’ lives to make sure that drunk people can get the All-Star Breakfast at 3:00 in the morning.

8 Hurricanes Got Human Names So That A Meteorologist Could Make Fun Of People

An Australian meteorologist named Clement Wragge started the whole tradition of giving names to weather systems. Back then, though, things weren’t quite as systematic as they are today. He just named storms after anything that popped into his head—which was usually the names of Greek gods and beautiful women. After a while, he gave up on the “Greek god” thing and started giving hurricanes human names—entirely out of spite. Some people felt that Wragge had too high an opinion of himself, and a few politicians started making jabs at him. As revenge, he named cyclones after them. For example, he named storms after Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin, the first two prime ministers of Australia, purely so that he could send out reports saying that Edmund Barton was “wandering aimless about the Pacific” and “causing great distress.”[3] This is why we give hurricanes human names today. Because a bitter, angry, Australian man thought it would be funny.

7 The First US Hurricanes Had Names Like ‘Easy,’ ‘Love,’ and ‘How’

The United States first started giving names to hurricanes in 1950. Back then, they didn’t use people’s names. Instead, they used words from the Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet. This led to some pretty strange storm names, like “Hurricane Easy,” “Hurricane Love,” and “Tropical Storm How.” The names didn’t exactly fit. “Hurricane Easy” was described as “the worst hurricane experienced” in its area in more than 70 years.[4] It devastated the town of Cedar Key, damaging 95 percent of the houses there and completely crushing the fishing community that propped up their economy. The real problem, though, was that they only had 26 names to choose from, so they ran out of names pretty fast. Soon, the government started naming hurricanes after women because hurricanes were “unpredictable” and temperamental. In the 1950s, this was something that people could just say out loud like everything was fine.

6 People Are More Likely To Donate To Hurricanes That Share Their First Initial

Strangely enough, a study has found that people are more likely to donate to hurricane relief if the storm’s name kind of sounds like their own. All it really takes is for someone to share the first letter of their name with a storm, and they’ll become up to twice as likely to donate. The researchers looked at Red Cross records and found that donations went up in every case for people who shared a first initial with the storm. The biggest effect was with Hurricane Katrina, likely because of all the media coverage it received. Normally, people whose names start with “K” make up 5 percent of donors. But “K” names made up 10 percent of the people who donated to Katrina. The researchers believe that people connect the disaster with themselves. When the storm’s name sounds like their own, they feel a sort of responsibility or affinity for it and so they actually do more to help.[5] One woman named Katrina actually raised $1,000 for victims of the storm specifically because she was thought the coincidence was cool. She told the press that she’d raised all that money because “I realized my name is going to go down in history as one of the biggest storms ever!”

5 Guards At The Tomb Of The Unknown Soldier Stay At Their Posts During Hurricanes

When a hurricane hits, there are some people who don’t get to evacuate: the men standing guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. This is the tomb where US soldiers who died without being identified are buried, and the guards who stand at its gate have a duty to honor the dead. When a hurricane hits, they don’t even go indoors. They stand outside, directly in the middle of the storm. During Hurricane Isabel, the guards were given special permission to hide inside the place if the winds went over 193 kilometers per hour (120 mph). But they didn’t do it. Instead, they stayed out in the middle of a hurricane, standing guard. During Hurricane Sandy, a single guard volunteered to spend 23 hours facing the winds. He risked his life to send out the symbolic message that the dead won’t be abandoned.[6]

4 US Hurricanes Start In The Sahara

The hurricanes that hit the United States have to travel an incredible distance. They get their start through a massive, complicated butterfly effect that begins all the way over in Africa in the Sahara Desert. In the Sahara, the blistering heat of the Sun sends air bubbles up into the sky to make massive storm clouds. Those clouds usually get pushed west toward the Atlantic Ocean—where they cause major problems. The hot desert storms will clash with the cold Atlantic Ocean air, and it’ll be enough of a cacophony to create a hurricane about 10 percent of the time.[7] This means that every hurricane that hits the US East Coast starts off with a fluttering of butterfly wings—or, literally, the beat of the Sun against desert sand.

3 Voodoo Practitioners In New Orleans Dropped By 90 Percent After Hurricane Katrina

Of all the ways that life in New Orleans changed after Hurricane Katrina, one of the biggest and most surprising impacts occurred in the voodoo community. Before the storm, New Orleans had 3,000 voodoo practitioners. After the storm, that number was all the way down to 300.[8] The people who performed voodoo were mostly low-income African Americans, the group that was hit hardest by the storm. A lot of them were stuck in New Orleans when Katrina hit, so a disproportionately large number of voodoo followers died during the storm. Others left the city and simply didn’t come back. Meanwhile, the few who remained were pulled out of their subcultural bubble. With so few practitioners left, they were forced to integrate into the rest of New Orleans culture. In many cases, they left their voodoo pasts behind. There’s a movement in New Orleans now to bring voodoo back. But 90 percent of the community has been wiped out, and most of the voodoo shops have been put out of business. After hundreds of years, the whole movement was decimated by a storm.

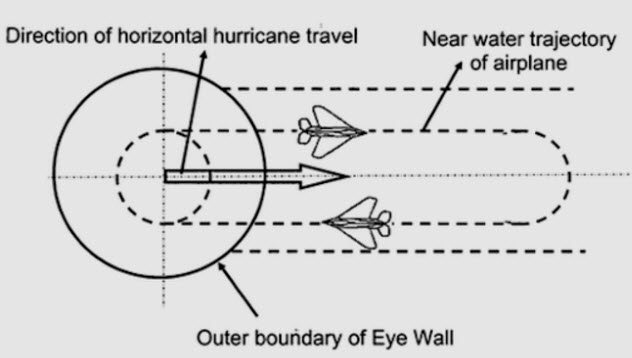

2 A Professor Thinks He Can Stop Hurricanes By Flying Jets Into Them

Professor Arkadii Leonov is pretty sure he knows how to stop hurricanes. “I cannot guarantee it would work,” he has admitted. But he thinks he can stop a cyclone by flying jets directly into them. His plan is to fly two supersonic jets directly into the eye of the storm. The jets will then start circling around the eye of the hurricane at Mach 1.5, creating a sonic boom of cool air that will completely destroy the storm in its tracks.[9] Leonov has been lobbying the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to try his idea. He says he can’t get the math to prove his idea will work. But he has a strong hunch and figures the NOAA should try it out and see what happens. The NOAA, however, is less convinced. “This is a bad idea,” they have told Leonov. But it may be “a great way to destroy a couple of airplanes and end the lives of their pilots.”

1 People Regularly Write To The Government Asking Them To Nuke Hurricanes

Many people believe that we can probably fix this problem with nukes. In fact, the government gets several letters every year from civilians begging them to nuke a hurricane. The government usually knocks this idea down, but they haven’t always done so. In 1961, the head of the US Weather Bureau announced that he could “imagine the possibility of someday of exploding a nuclear bomb on a hurricane far at sea” and that he was fairly certain it would work. In 1959, a man named Jack Reed actually developed a full plan to do it. He was going to send a submarine right into the storm so that it could launch multiple nuclear missiles right into the eye of the hurricane. He believed that the nukes would displace the warm air in the hurricane’s eye and replace it with colder, denser air to weaken the storm. Again, the NOAA isn’t thrilled. “Needless to say, this is not a good idea,” they have said. Aside from the fact that this almost certainly wouldn’t work, it would send radioactive fallout through the trade winds and across the world. Even if it did obliterate the hurricane, it might not be worth trying to nuke the problem away.[10] Read More: Wordpress