Despite this, people persevered. They went through the motions from newborns struggling to survive, to fully-fledged citizens of the Roman Empire.

10Being Welcomed into the Family

In ancient Rome, the pater familias was the uncontested head of the household. He was granted complete authority both by Roman law and mos maiorum (the collection of unwritten customs and traditions). He was the only member of the family allowed to own land and was expected to represent the family in legal, business, and religious affairs. Even though pater familias meant “father of the family”, the father did not always occupy that role. The pater familias was the oldest living male, so if the father died, the eldest son would take his place. This is one of the reasons why Romans placed a high value on having sons, and male adoption was a common occurrence. Any new baby had to be accepted by the pater familias. Traditionally, the midwife placed the newborn at his feet, and only if the pater familias picked it up would the baby become a formal part of the family. The father had the authority to disown and sell his children into slavery should they anger him. He was even allowed to kill them, although records show this was a rare occurrence and was eventually outlawed by Augustus.

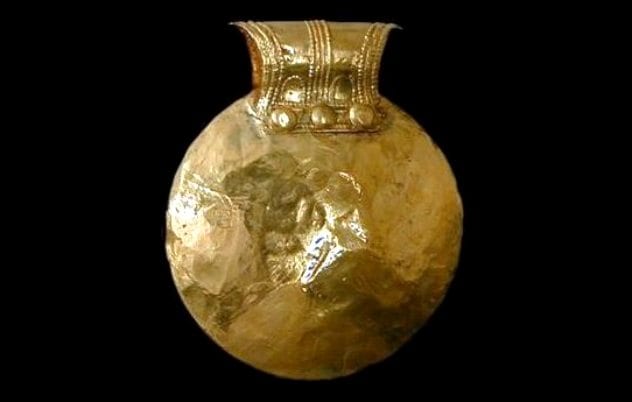

9Receiving the Bulla

Due to high infant mortality rates, children were not given a name when they were born. Instead, Romans waited for a week before naming the child during a celebration called the dies lustricus (“day of purification”). Much like a modern birthday, friends and family visited to offer the baby gifts and well-wishes. Male children also received a bulla at this celebration. The bulla was a pendant meant to ward off evil spirits, as well as signify the boy’s status as a freeborn citizen of Rome. Scholars still debate whether Roman girls also wore a bulla or if they had a different type of amulet called a lunula. Boys were expected to wear their bullae until they reached adulthood while girls wore their pendants until their wedding day. Typically, a bulla was made out of gold but this would only be available to the wealthy elite of Rome. The lower classes made do with bullae made from affordable materials such as leather, bronze, or tin.

8The Stages of a Child’s Life

A Roman childhood had several clearly defined stages, both from a social and a legal perspective. The first period was known as infantia. It lasted from birth until the age of seven, both for girls and boys. This time was spent mostly at home being looked after by parents, grandparents, guardians, and older siblings. All children who were infantes or infantiae proximus (slightly over the threshold) were considered doli incapax—incapable of guilty intentions in the eyes of the law. Until the ages of 12 and 14 for girls and boys, respectively, children were impuberes, or pubertati proximus in the cases of those close to reaching the threshold. They were still presumed doli incapax, although legal evidence could be presented that said otherwise. Socially, children started to explore the world at this stage. They would leave the house more often, spend time in the company of strangers, and even begin an education away from home if their parents could afford it. Girls older than 12 were suitable for marriage. At age 15, boys passed into manhood. They were granted legal privileges and responsibilities, although Roman law still considered them adolescents until the age of 25.

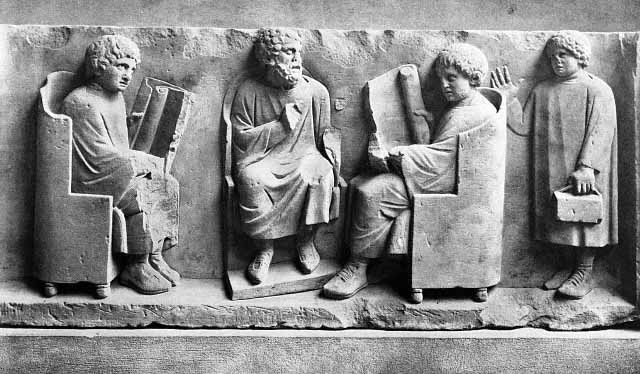

7Getting an Education

As with many societies, education in ancient Rome was mostly available to the rich. Rough estimates placed literacy levels at around 20 percent, although it varied based on time period. During most of the Roman Republic, education remained an informal practice involving parents passing down knowledge to their children. However, after the conquest of Greece in 146 B.C., the Greek education system started spreading through the empire. Romans started placing more importance on education, and tutors became more accessible as many of them were slaves. Children typically went to school when they turned seven. Their teacher was called a litterator who taught reading, writing, basic arithmetic, and perhaps some Greek. At age 12 or 13, children who could afford an advanced education would go to a “grammar school”, taught by a grammaticus. Here they moved past the practical knowledge needed for everyday life and began studying arts and poetry. The highest levels of education involved learning rhetoric by studying the works of great orators such as Cicero and Quintilian.

6Playing Around

Children of ancient Rome spent a lot of their free time playing with toys quite similar to ones from modern times. Infants were often entertained with a rattle called a crepitaculum. It was made out of wood or metal and sometimes had bells on it. Besides acting as a toy, it is possible the Romans also used it as a ward similar to the bulla. Dolls and puppets were the most common toys for girls. These were made out of a wide range of materials such as terracotta, wax, clay, wood, metal, and stone. Some of them even had articulated limbs, while others could be dressed and accessorized with jewelry. Boys preferred moving toys such as carts or horses with wheels. Wooden swords were also common so they could pretend fight. Hoops, kites, balls, and spinning tops were common toys available for children of all ages. Board games were popular with young and old alike. They had a variety of games using dice, knucklebones, and stone pieces. Other games included hide-and-seek, leapfrog, and terni lapilli (tic-tac-toe).

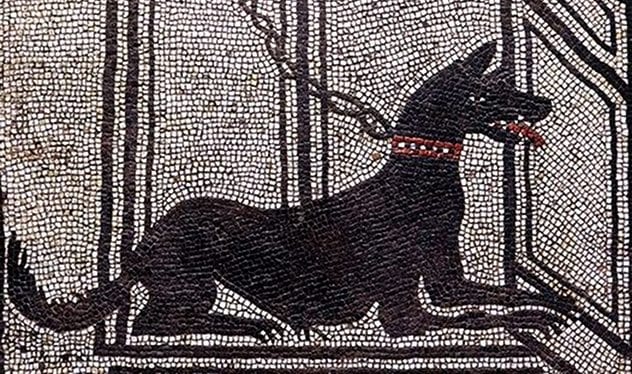

5The Family Pet

Like us, the ancient Romans were fond of animals and many households had one or more pets. Cats were common pets, as were various Old World monkeys such as Barbary macaques. It seems that even in ancient times, people were amused by the antics of our simian cousins. Several authors and poets make mention of monkeys and the mischief they caused. Snakes were also kept as pets, although they were more of a religious symbol and were unlikely to be found in an average household. Many wealthy families preferred to keep birds because they also served as a status symbol: their special dietary needs and upkeep placed them out of the range of a typical Roman family. Apparently, even in Roman times, dog was man’s best friend. It was, by far, the most popular pet of ancient Rome, featuring in literature, pottery, paintings, and bas-reliefs. Unlike other pets, dogs also served practical functions as hunting companions and watchdogs. As the mosaics in Pompeii showed, more than a few Roman houses came with the inscription “Cave canem”—“beware of dog”.

4Finding a Job

The social status of a boy’s family usually dictated what kind of job he could be eligible for once he became a teenager. The most prestigious positions were in politics, but these were normally reserved for the elite and required an extensive education. Slightly lower down the totem pole were administrative positions within the empire: tax collectors, notaries, clerks, lawyers, teachers, etc. Again, these jobs were typically available to young men with a strong education, although some of these positions were also available to educated slaves, particularly the Greeks. The most accessible choice for most Roman freemen was to join the army. As a militaristic empire, Rome was rarely short on wars and always had a need for soldiers. This was also a good way for the lower classes to secure a steady income and even earn land once their 25-year service was over. As the empire grew, so did the variety of jobs. Soon enough, a Roman adolescent could choose to become a merchant, an artist, an entertainer, or a tradesman. However, these positions were typically passed down from father to son. Alternatively, the family needed a connection in order to secure their child an apprenticeship with a master.

3Getting Married

Male children did not really have to concern themselves with marriage since men typically married in their mid-twenties. Girls, however, married much younger, as early as age 12. Since most girls did not receive the kind of extensive education afforded to boys, there was no point in keeping them around the house after they reached childbearing age. Girls from wealthy families usually married younger than girls from working class families. Their potential marriage was seen as a rare opportunity to climb the social ladder. Most parents would not want to jeopardize this valuable commodity by letting their daughters get too old or lose their chastity. Most girls had little say regarding their future husbands. Like most of their life’s decisions, this one was made by the pater familia. He would be on the lookout for prospective husbands and make the necessary arrangements with the boy’s family. The wedding featured numerous customs which evolved over the centuries, and some are still found today. These include the wearing of white and carrying the bride over the threshold.

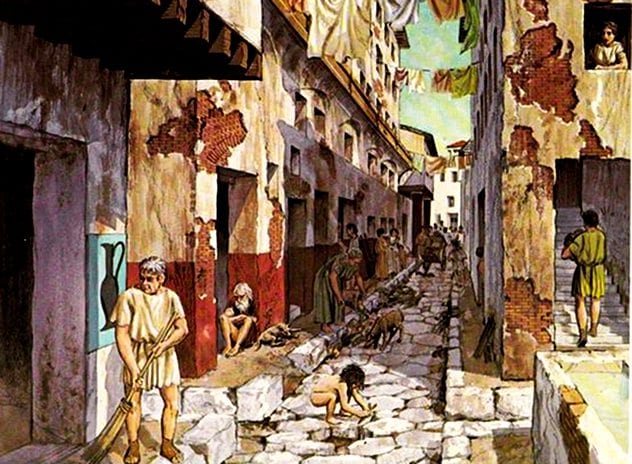

2Finding a Place to Live

At its peak, ancient Rome was home to over one million people, a feat that would not be repeated in Europe until Industrial-era London. This forced the government to come up with impressive innovations such as the aqueducts and the Cloaca Maxima sewage system to deal with the ever-growing populations. It also meant that Rome was one of the most crowded places to grow up in. Two types of residential housing were common in the city. The rich could afford a domus—a large house with multiple rooms, an interior courtyard, and, in some cases, shops that faced outside called tabernae. The ultra rich also had villas outside the hustle and bustle of Rome. Most of the population, however, was crowded into apartment blocks called insulae. As construction technology improved, so did the height of these buildings. Some insulae could reach eight or nine stories. Third-century records show there were around 44,000 insulae in Rome. It was not uncommon for an entire family to live in just one room. The floor you lived on was often inversely proportional to your social status. The bottom floor was taken up by tabernae and other places of business. The first couple of stories had more spacious and more expensive apartments. As the floors kept climbing, they not only got more cramped but also more dangerous. Fires were a common occurrence in Rome, and tenants living on the top floors were often trapped in burning buildings. Augustus brought the legal height limit of insulae down to 70 Roman feet (20.7 meters), and Nero lowered it again to 60 Roman feet (17.7 meters) after the Great Fire.

1Becoming a Man

Reaching sexual maturity was an important stage in the life of Roman adolescents. Girls were expected to remain virgins until they got married. They did not have extensive maturation rituals, and their wedding night typically functioned as their rite of passage. Boys reached sexual maturity when they were 15-16 years old. Besides leaving behind their bulla, they also underwent a wardrobe change—they replaced their “toga praetexta” with the “toga virilis”—the plain white toga worn by adult males. Romans celebrated the coming of age of young men at the Liberalia, a festival marked by food, wine, song, and dance. In fact, Liberalia was associated with the older, more lavish Bacchanalia dedicated to the god of wine and fertility, Bacchus. After the Senate made efforts to suppress the Bacchanalia, similarities between the two festivals caused them to merge together. A sixteen-year-old Roman male could pursue sexual relationships before marriage. A man from a wealthy family would likely have sex with a slave, while a commoner would visit a prostitute. Both these kinds of relationships were considered acceptable for men even after marriage. Adultery was typically regarded only between a married man and a Roman wife or unmarried daughter.