While the skeleton trade boomed, other gruesome jobs were created to support it. Some collected dead bodies from the poorhouses, and one could get quite wealthy collecting bodies from foreign battlefields. Hospital janitors made extra money picking up body parts that had been sawed off from the living, and there may have even been a bit of grave robbing for the more daring ghouls.

10 Bone Oils

Maitre Mazzur was the only person in the United States with this special skill set. Based in New York City in 1876, Maitre Mazzur was able to “extract the oil from human bones” so that the display skeletons did not give off a bad odor. If a doctor were to buy a full skeleton set from anyone else in the US, his skeleton would stink up his office with the smell of death and rot. The process for removing the stink was a secret of the trade. Mazzur had gained his knowledge by studying in Paris where the best skeleton display makers were stationed, and he was not going to spill his secrets to anyone in the US. No one was allowed inside his little workshop on Bleecker Street, and the man was said to keep well to himself. During Mazzur’s time, about 500 skeletons were imported into NYC each year for colleges and universities, medical students and doctors, artists, and people who liked to collect odd things. The rest of the display skeletons were local and cobbled together from multiple sources. They included parts found in hospitals that were collected by janitors.[1]

9 Quality Of Skeletons

There were different classifications for the quality of complete skeletons. A No. 1 skeleton was a top-of-the-line set of bones made for well-established medical doctors who could afford the $800 price tag back in 1891. At the bottom end of quality were the composite skeletons. These composites were made from the bones of multiple donors instead of just one person. The skull could be from one person, the right arm from another, and the pelvis from yet another source. These composite skeletons were very common and were often sold to sideshows as gruesome displays, to theaters, and to chambers of horror. They had little value for medical studies and were often a bit lopsided because the bones came from so many people of different sizes. Composite skeletons were sold for roughly $150 as long as they were made using the skull from a real person. Composite skeletons that included imitation bones made from compressed paper pulp fetched much less and were often sold to secret fraternal orders.[2]

8 Work Dedication

M. de Robaire had a small shop in Philadelphia in 1891. Above the entrance to his business and home was a sign that read “Perfumerie,” but what was on the second floor and in the closets of the business was as far from scented oils as one could get. De Robaire was a skeleton dealer. As his neighbors were very superstitious and he did not want to attract negative attention, he ran a perfume business on the first floor as a cover business. A single man from France, de Robaire kept mostly to himself and spent much of his time in his workroom on the second floor. There, he put together skeletons to be sold, mostly to secret clubs and organizations. His bedroom, also on the second floor, doubled as his storage room. The walls where he slept were covered in skulls and crossbones. There were full skeletons on display, and each of the four posts of his bed was topped with a skull. To provide quality skeletons, de Robaire imported most of his bones from France. He claimed that American and German bones were merely boiled and came out rough to the touch. French bones underwent a cleaning process that took two to three months, and the bones were always white and polished. Upon receipt of the bones, de Robaire would piece them together, making full skeletons that were said to be some of the best-constructed skeletons in the country.[3]

7 Preparation Of The Bones

Preparing bones for display skeletons was a tedious and gruesome process in France in 1892. Beginning with a corpse, a scalpel was used to remove all the fat, muscle, and tissue from the bones. After all the meat was cleaned off, the bones were boiled. During this process, the bones had to be carefully watched to ensure that they were not overboiled and turned rough. Next, the bones were treated in the sun. This bleached the bones white and caused the remaining grease inside the bones to leak out. Finally, the bones were given their brightness with ether and benzene as well as other secret chemicals. The chemical treatment is what set the French bones apart from bones prepared in other countries. They were said to never turn yellow, and the bones would not emit any foul odors in hot weather. After the tedious process of preparing the bones for display, a master of the bones would begin assembling the spinal column with a brass rod. Brass wires were used to hold the rib cage in place. Hinges and hooks were used to assemble the rest of the skeleton so that it could move the way it would have done if it was still inside its meat.[4]

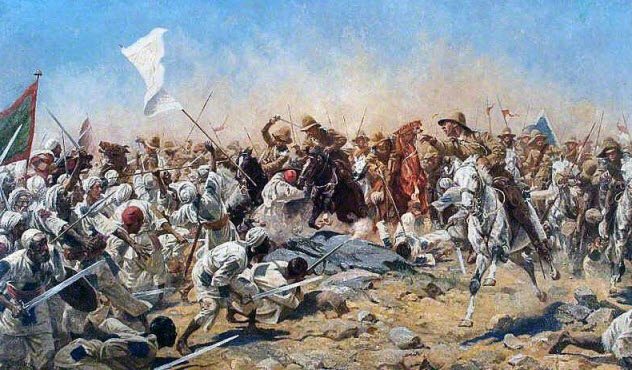

6 London Gets Its Bodies

In London in 1899, unclaimed bodies from the workhouses and hospitals were first dissected and then, if all the bones were present, the bones were cleaned for full skeleton displays. Unfortunately for those in the business, there simply were not enough bodies to meet the demand. Instead, bone collectors had to wait for battles to take place and then harvest the complete, unbroken bodies of the enemies left in the fields. This happened after the Battle of Omdurman, and newspapers across London reported that the bodies of dervishes were being converted into marketable skeletons. Skeleton dealers assured the public that no British soldier would be used in the making of their skeleton displays. In fact, the dealers claimed that the strong bodies of the dervishes made the finest and whitest skeleton displays. Furthermore, the dervish skeletons were set to bring in high prices compared to the skeletons obtained from the London workhouses.[5]

5 The British Grew Terrible Bones

By 1900, everyone from curio collectors to medical doctors was madly scrambling to get a fine set of dervish bones. Meanwhile, the bones of the British were ranked as the poorest quality bones to own. According to the trade, the bones of the British were often stunted and very yellow. No matter how much bleach was used to whiten British bones, they always seemed to hold a yellow tint in them. The bones of the French, however, were quite desirable among collectors. The French grew fairly strong bones that were easily whitened and polished. The complete skeletons of the French were priced in the mid-to-high ranges depending on the quality of the work done on them. There is little doubt that the diet and working conditions of the British people contributed to the poor quality of their bones, although this could be seen as a benefit for those who squirmed at the thought of being stripped of their flesh and put on display for the world to see.[6]

4 Sell Your Own Bones

Short on cash? Selling your bones before you died was rather common in the past. For example, a story was published in 1907 about a young man who had only been married for a few months. As cruel fate would have it, the young man got into an accident, lost his leg, and was slowly dying from internal injuries. He decided to do one last thing for his beloved wife before he moved on to the great beyond—sell his bones. He was given $50 in advance for his skeleton. His wife was brought into the hospital to see him one last time, and he gave her the money as a parting gift.[7] If you were not on the cusp of death, you could still earn money from other people’s bones. Explorers and travelers would often return to London or Paris with the bodies of indigenous people from around the world. These were sold to the body dealers who, in turn, sold them to those who made the skeleton displays.

3 Criminal Heads

The French often preserved the skulls of criminals because their executed remains were usually left unclaimed by the families. In some of the skeleton warehouses of France in 1913, particularly in Paris, there was a room dedicated to the skulls of criminals. These skulls were often labeled with the criminal’s name and the date of his execution. Some of them even had their own pamphlets that described their crimes in great detail. These skulls were for sale and were collected by the curious as well as doctors. Furthermore, the skulls and skeletons could be rented for a fee. If one did not have the means to purchase some bones outright, the person could rent them for the time needed, such as for a lecture or for some gruesome public display for thrill seekers.[8]

2 Spare Parts

Parts of skeletons, casually referred to as spare parts, were also big in the skeleton trade. These parts were often gathered from hospitals after an amputation or during a dissection. They were cleaned of all their meat, bleached, and then placed in neatly numbered boxes in warehouses. Although some were used to make composite skeletons, most spare parts were used as replacements for broken or lost bones. For example, if your full-size skeleton was attacked by the family dog and lost a toe, you would send your incomplete skeleton to one of the great bone warehouses where it would be fitted with a new bone. Nearly all major cities in Europe had a bone warehouse or two. These special warehouses were kept secret from the public for mostly superstitious reasons. If you were fortunate enough to make the right connections, all types of bones, from parts to complete sets, would become available to you for a cost. The ages of the bones could range from infant to adult.[9]

1 Britain’s Trade Slump

In 1948, three years after World War II, Parliament came to a horrifying realization. British exports of human skeletons were in rapid decline. While art schools, hospitals, and medical schools were desperately trying to get their hands on real human skeleton displays, there simply were no bones to be had. It was joked about that Parliament would soon consider printing up posters that read, “Hurry up and die and help the Export Drive.” But the handwriting was on the wall. The skeleton industry was slowly dying out. Plans were already being made by bone dealers to start making skeletons out of plastic, using brass springs and catgut to give the skeletons the same mobility as the real skeleton displays.[10] Elizabeth lives in the beautiful state of Massachusetts where she is currently involved in researching early American history. She writes and travels in her spare time.