Some speakers, given an opportunity to have their say, make the most of it and decide to let the audience know exactly what is on their mind. Rather than offering easy-to-digest platitudes, the following people chose to use their time at the podium to “put the boot in,” which, if you’re unfamiliar with the expression, essentially means to cruelly, mercilessly attack someone.

10 Charles Spencer At Princess Diana’s Funeral

When Earl Spencer stood up to speak at his sister’s funeral, he appeared to be quite calm. Or as calm as anyone could be with half the world watching. He began his speech by talking about the shock of Princess Diana’s death and the sorrow that people who knew her felt, all of which seemed entirely conventional and uncontroversial. He praised her compassion, her sense of duty, and her “natural nobility.” This was the first hint of what was about to come, because Diana’s in-laws (with their presumed unnatural nobility) were sitting on the front row, and millions of people were watching their reactions. For the next five minutes, they had to nod solemnly while he ripped into them in his genteel English manner. He said, “Genuine goodness is threatening to those at the opposite end of the moral spectrum,” and though he didn’t specify who “those” at the opposite end of the spectrum were, everyone listening could take a pretty good guess. He “pledged” himself to protect her sons, saying, “We will not allow them to suffer the anguish that used regularly to drive you to tearful despair.”[1] Finally, he finished his speech with the words, “I pledge that we, your blood family, will do all we can to continue the imaginative and loving way in which you were steering these two exceptional young men, so that their souls are not simply immersed by duty and tradition but can sing openly as you planned.” Ouch.

9 David Trimble’s Nobel Peace Prize Acceptance Speech

In 1998, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded jointly to John Hume and David Trimble “for their efforts to find a peaceful solution to the conflict in Northern Ireland.” John Hume was the Catholic leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, while Trimble was the Protestant leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, and they had both been working tirelessly on the Good Friday Agreement to bring peace to their country. If you win the Nobel Peace Prize, it might be assumed that you are a peaceful sort of guy. We might reasonably expect Nobel acceptance speeches to talk about “unity,” “acceptance,” or “tolerance.” And you are expected to keep on saying it. But when David Trimble jointly won a Nobel Peace Prize, he decided to go with something different. His speech seemed to be remarkably, well, grumpy. The trouble started with, “It is a truth universally understood that there is no such thing as a free lunch. That being so, John and I are obliged to sing for our supper. In short some expect us to speak . . . ” Considering that he had just shared a million-dollar prize, it seemed a little churlish to be annoyed when asked to speak while accepting it. The speech also ended on a less-than-hopeful note: “But common sense dictates that I cannot for ever convince society that real peace is at hand if there is not a beginning to the decommissioning of weapons [ . . . ] Any further delay will reinforce dark doubts about whether Sinn Fein are drinking from the clear stream of democracy, or is still drinking from the dark stream of fascism. It cannot for ever face both ways.”[2] Trimble’s speech in Oslo caused widespread anger at home, which was compounded when he later called Southern Ireland “a pathetic, sectarian State.”

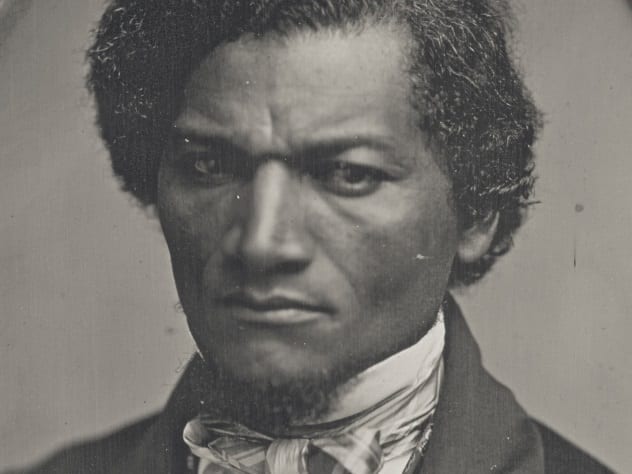

8 Frederick Douglass On The Fourth Of July

Frederick Douglass was a former slave, political activist, and public speaker. He had a prominent role in the abolitionist movement during the Civil War, and he continued to speak for human rights until he died in 1895. In one of his most famous speeches, delivered on July 5, 1852, he posed the question, “What to the slave is the Fourth of July?” And then he answered it: [It is] a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.[3] That’s telling it like it is. After the abolition of slavery, Douglass continued to campaign for civil rights. He died of a heart attack on his way home from a women’s suffragist meeting in 1895. Douglass toured America giving speeches about civil rights. The Fourth of July speech received a rousing reception and was repeated often, becoming his most famous.

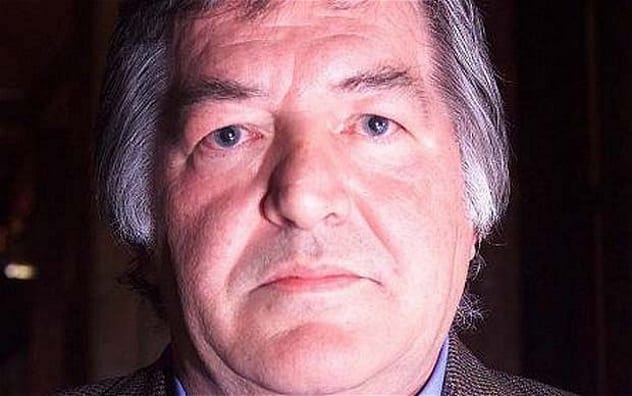

7 Noel Botham On The Death Of Hughie Green

Noel Botham was a journalist and biographer with an eye for the main chance. In 1997, when he was asked to speak at the funeral of Hughie Green, a popular TV presenter, he must have seen it as a great publicity opportunity, which is nice. He stood up in front of Green’s family, including his children and grandchildren, and spoke about Green’s four mistresses and numerous love children, one of whom was now one of the most famous faces in British television. Botham claimed that Hughie Green had known and approved of the speech that he was going to give at the funeral.[4] Although Botham did not name the famous love child at the funeral, he later accepted £100,000 from a newspaper to reveal that it was Paula Yates, the former wife of Live Aid organizer Bob Geldof. Yates had recently suffered the loss of her new fiance, INXS singer Michael Hutchence. Paula Yates was distraught at the revelation. She never recovered from the hurt of finding out, and the news was thought to have contributed to her death from a heroin overdose in 2000.

6 Nikita Khrushchev On Josef Stalin

When the newly appointed Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, addressed the 20th congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956, the audience was more than a little nervous. There had not been a congress since their previous leader, Josef Stalin, had died, and no one knew quite what to expect. Certainly, no one could have predicted what Khrushchev did. In a closed session, Khrushchev denounced Stalin, his crimes, and the imprisonment, torture, and execution of party members. He said, “Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation, and patient cooperation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion. Whoever opposed this concept or tried to prove his viewpoint, and the correctness of his position—was doomed to removal from the leading collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation.” He went on to talk about the dangers of the “cult of the individual.” Stalin, whose image had been everywhere during his reign, had confused loyalty to the party with loyalty to the leader of the party and punished anyone who disagreed with him. Khrushchev added, “Stalin originated the concept enemy of the people. This term automatically rendered it unnecessary that the ideological errors of a man or men engaged in a controversy be proven; this term made possible the usage of the most cruel repression, violating all norms of revolutionary legality, against anyone who in any way disagreed with Stalin, against those who were only suspected of hostile intent . . . ”[5] His audience sat stunned, not daring to move or even look at each other while Khrushchev talked for four hours. They were too stunned, or perhaps frightened, to applaud, and Khrushchev left the stage to deafening silence. Though the speech had been made in closed session, it was somehow leaked to the media, and Stalinism was officially over.

5 Ann Widdecombe On Michael Howard

In 1997, it was well-known in British political circles that the prisons minister, Ann Widdecombe, had a difficult relationship with her boss, Michael Howard. Widdecombe was also known to be extremely plain-speaking. So, when the two clashed in Parliament over the sacking of the head of the prison service, the House of Commons was packed with MPs who wanted to see the show. Widdecombe said the sacking was “unjustly conceived, brutally executed, and dubiously defended,” which seems to be fairly mild parliamentary language. However, Michael Howard took exception and began a smear campaign against his former junior, implying that she had been having an affair with the head of the prison service. Widdecombe, who had famously stated that she was a spinster and a virgin, was incensed. The warring colleagues appeared on a news program, where Mr. Howard was challenged 14 times about the sacking of the prisons officer, but he refused to answer. The following week, the two met again in the House of Commons, and this time, it was packed not just with MPs but also with members of the press. Widdecombe alleged that there were at least three occasions when Howard had deliberately misled Parliament. She spoke for 45 minutes, famously ending with the statement that there was “something of the night” about Michael Howard, a phrase which followed him around for the rest of his career, which was brief. He made a bid for the leadership of the Conservative Party a short time later and came last in the vote.[6]

4 Nellie McClung On Universal Suffrage

Nellie McClung was a Canadian suffragist. Her political activism began when she joined the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, campaigning against alcohol abuse. In 1912, she became a founding member of the Political Equality League. She and her fellow members staged a mock parliament which held a debate satirizing the dangers of allowing men to vote. McClung mocked a speech that had been made by Manitoba’s premier, Rodmond Roblin, saying, “Man has a higher destiny than politics,” and that his responsibility was to look after his family. After all, he couldn’t be earning money if he was bothering himself with the affairs of the day.[7] The speech was an instant success, producing howls of laughter from women who recognized the arguments that had been used against them, but despite appeals to Roblin, who seemed not to enjoy being mocked, he refused to back the idea of women’s suffrage. In 1915, Roblin’s government collapsed. McClung agreed to make a speech in support of Tobias Norris in return for his support on votes for women. In it, she said, “I am not here to beg a favour but to obtain simple justice. Have we not brains to think? Hands to work? Hearts to feel? And lives to live? Do we not bear our part in citizenship? Do we not help to build the empire? Give us our due!” Norris’s party was elected, and women were granted full suffrage.

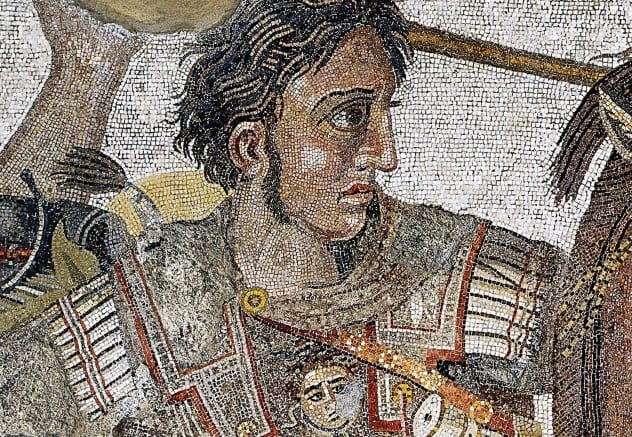

3 Alexander The Great To His Army

Alexander the Great was an outstanding military leader. He had led his army undefeated for ten years, but on the eve of the Battle of the Hydaspes in India, he learned that his men were worried about the overwhelming odds against them. And, as all great leaders do, Alexander confronted the issue head-on. He began in conciliatory terms, “I observe, gentlemen, that when I would lead you on a new venture you no longer follow me with your old spirit. I have asked you to meet me that we may come to a decision together: are we, upon my advice, to go forward, or, upon yours, to turn back?” No one spoke. He went on to list their achievements over the last ten years, pointing out the lands they had conquered, and then questioned their courage: “Are you afraid that a few natives who may still be left will offer opposition? Come, come! These natives either surrender without a blow or are caught on the run—or leave their country undefended for your taking.” More uncomfortable silence. He finished by saying, “I could not have blamed you for being the first to lose heart if I, your commander, had not shared in your exhausting marches and your perilous campaigns; it would have been natural enough if you had done all the work merely for others to reap the reward. But it is not so. You and I, gentlemen, have shared the labor and shared the danger, and the rewards are for us all. The conquered territory belongs to you [ . . . ] whoever wishes to return home will be allowed to go, either with me or without me. I will make those who stay the envy of those who return.”[8] They all stayed. And they won. It was Alexander’s last great conquest.

2 Geoffrey Howe’s Resignation Speech

Geoffrey Howe served as the finance minister under Margaret Thatcher’s government and was once considered to be one of her most loyal colleagues. However, they’d had several disagreements, and he suddenly found himself frozen out of Thatcher’s inner circle. Howe was famously considered to be a mild-mannered man. One opponent described his political attacks as having the ferocity of “being savaged by a dead sheep.” So, when Geoffrey Howe rose to make his traditional resignation speech in 1990, his colleagues could not have anticipated that he was about to bring down Margaret Thatcher completely. He began his speech in conventional form, summing up his long career as an MP and a cabinet minister. But then he began to talk about Thatcher, her attitude toward the European Union, and the way that she conducted meetings: like a tyrant ignoring the advice of her cabinet. He claimed that she was hampering her colleagues’ ability to negotiate with Europe, saying, “It is rather like sending your opening batsmen to the crease only for them to find, the moment the first balls are bowled, that their bats have been broken before the game by the team captain.”[9] The speech blew the Conservative Party apart. Before long, knowing she was going to lose a leadership challenge, Margaret Thatcher resigned.

1 Ferenc Gyurcsany And The Oszod Speech

Ferenc Gyurcsany’s mother probably told him that honesty was the best policy. Which it is. Most of the time. However, when the Hungarian prime minister stood up to address his party in closed session in 2006, he might have done well to consider that other well-known proverb about discretion and valor. Gyurcsany began his speech conventionally enough but soon moved into dangerous territory. Perhaps he had always intended to be so honest, or perhaps he got carried away in the heat of the moment. Talking about the political and economic situation in his country, he said, “We have f—ed it up. Not a little but a lot. No European country has done something as boneheaded as we have. It can be explained. We have obviously lied throughout the past one and a half to two years. It was perfectly clear that what we were saying was not true.” And then, he went on, “We did not do anything for four years. Nothing. You cannot mention any significant government measures that we can be proud of . . . ” He ended his speech on a note which turned out to be prophetic. “Divine providence, the abundance of cash in the world economy, and hundreds of tricks, which you do not have to be aware of publicly, have helped us to survive this. This cannot go on. Cannot.”[10] A tape of the meeting was leaked to the press, which caused riots in the streets by all those citizens who had been lied to, followed, a few weeks later, by a landslide defeat for his party in elections. Gyurcsany himself, however, remained in politics and even survived a no confidence vote on his leadership. Perhaps, after all, honesty does pay. Ward Hazell is a writer who travels, and an occasional travel writer.