10 A Royal Easter Tradition

Back when Easter was the most important event for the Russian Orthodox Church, people would take hand-painted eggs to church, have them blessed, and then hand them out to loved ones. Add that to the upper-class tradition of exchanging bejeweled gifts on Easter, and one can understand how the idea for the Faberge eggs came about. It began in 1885 when Tsar Alexander III wanted to surprise his wife, Empress Marie Fedorovna, with something special that year. On Easter, he presented her with the deceptively simple-looking egg that started it all, the Hen Egg. He was so pleased by her thrilled reaction that he subsequently presented Marie with another egg every year thereafter. Their son, Tsar Nicholas II, continued with the tradition, giving a precious egg to both his mother and his own wife every Easter. It became the most lavish and exquisite Easter tradition anyone had ever seen. But after only 32 years, the glittering gifts stopped abruptly with the murder of Nicholas II and his entire family during the Russian Revolution.

9 The Surprises Inside

Master jeweler Peter Carl Faberge was given complete artistic freedom and could design the eggs around any theme he wanted. But he had to abide by one rule: Every egg had to contain a surprise. Faberge didn’t disappoint his imperial patrons. Within each ornate shell, he hid a tiny marvel. The Hen Egg cracked open to reveal a golden yolk. Inside the yolk nestled a pure gold hen, giving the Hen Egg its name. Within the hen was a tiny diamond replica of the royal crown and a miniature ruby egg pendant. Just a few of the other surprises include a mechanical swan, an elephant, a golden miniature of the palace, 11 tiny portraits on an easel, and an exact working replica of the Coronation carriage that took nearly 15 months to create. Despite his enormous freedom with the designs of the eggs, Faberge always made them a tribute to something in the royals’ lives. The Red Cross Egg, for example, was created in 1915 to honor the Empress Alexandra Fedorovna for her efforts in the Red Cross charity during World War I.

8 They Were Once Despised

While the royals couldn’t get enough of the precious, oblong treasures, the Bolsheviks viewed them with hatred. They became a symbol of the wasteful elite during times when disastrous harvests and hunger made life for the common people miserable. But the disgruntled Bolsheviks didn’t just stew over it; they went after Faberge with ill intent, and the master craftsman had to flee the country. Faberge’s son Agathon was kidnapped and imprisoned in the Kremlin, where he was forced to work for the revolutionaries by evaluating the valuables that previously belonged to the Romanovs. Agathon eventually escaped and settled down in Finland. Faberge’s wife fled separately with another son. They found safety in Switzerland, where they were reunited with Faberge. But his business in Russia was nationalized and eventually closed down in 1917. By that time, Faberge luckily already had branches open in other countries that the Bolsheviks’ influence couldn’t reach, notably in England.

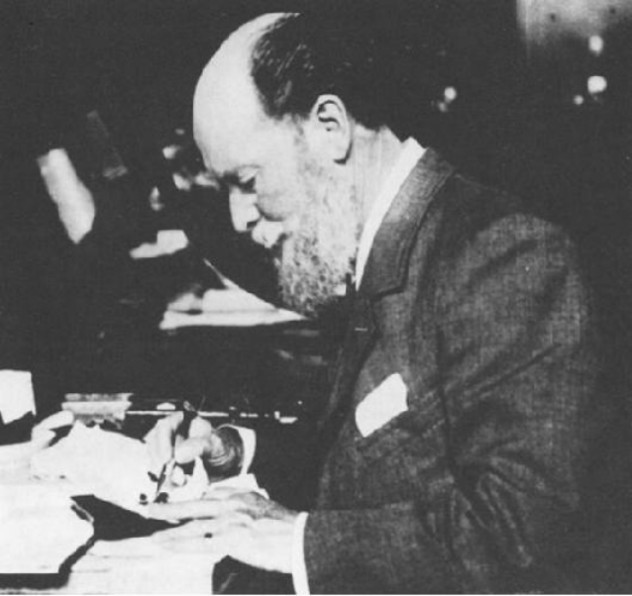

7 Peter Faberge Wasn’t Russian

While Peter was born in Russia, he was of French and Danish descent. His paternal family came from France as fleeing French Huguenots and eventually settled in their new country. Faberge’s father was part of the first generation of the family born in Russia and eventually married the daughter of a Danish artist. She gave birth to Faberge in 1846, and his renowned master goldsmith father took him on as an apprentice when he was old enough. Proving to be a superbly talented student, Faberge was later educated by goldsmiths in France, Germany, England, and Italy. In 1872, he finally returned to St. Petersburg to join the family business. He displayed such skill at his trade that he became the royal court’s jeweler. Foreign royals, including those from Norway, Sweden, England, Greece, Bulgaria, and Siam, also commissioned him. After the revolution, Faberge never returned to Russia and lived to be 74, passing away while on a visit to one of his sons in Lausanne.

6 Stalin Inadvertently Saved Them

After the fall of the royal family, the Bolsheviks went on a five-finger discount spree through all of the palaces. It was during this time that some of the eggs vanished as loot while the rest were confiscated and stored in the Kremlin’s vaults. They were forgotten until 1927, when Stalin rooted through the vaults for valuables to finance his regime. His intention was not to save them, and he secretly sold 14 of the valuable eggs for embarrassingly little money on the foreign markets—much to the grief of Russian curators. But save them he did! A second option that existed at the time was to melt down the Imperial eggs for their precious metals, but thanks to the sales, that never happened. One of Faberge’s most incredible eggs survived because of Stalin. The Peacock Egg is a crystal and gold masterpiece that contains an enameled peacock. When taken off its golden branch, the automated bird fans its tail out like a real peacock and even walks.

5 The Ultimate Easter Egg Hunt

Fifty eggs were made for Russia’s ruling family in total, but due to the Russian Revolution, Stalin’s sticky fingers, and anonymous collectors, seven of them are now lost to time. The most intriguing is perhaps the Necessaire Egg, made in 1889. Encrusted with precious stones such as emeralds, diamonds, and rubies, it was last seen in a London shop in 1949. The owner sold it for £1,250 to a nameless man who put down the hard cash and walked out with the tiny treasure, never to be seen again. While experts believe that some of the missing Easter eggs could have ended up in the United States, Russia, and England, they also fear that the works of art might have been destroyed sometime in the past. That may be why nobody’s coming forward with the missing seven. The incentive to reveal one in your possession or even to hunt for the artifacts is quite strong, too—Faberge eggs can sell for up to $30 million.

4 One Was Bought As Scrap

The lost Third Imperial Easter Egg was one missing egg that was found in an amazing way. Made from gold and studded with precious stones, it was sold to an American for $14,000. The scrap dealer, who remains anonymous, estimated that he could make at least $500 in profit by selling it as scrap gold to be melted down. But when he failed to get any buyers, he researched the object on the Internet and only then realized what he’d stumbled across. Faberge expert Kieran McCarthy examined the object. To the joy and amazement of the art world and Faberge fans everywhere, he declared that it was the long-lost Third Imperial Easter Egg. Even its surprise was still intact—a tiny bejeweled Vacheron Constantin watch. The scrap dealer didn’t get the $500 he was hoping for. Instead, he received about $33 million. The egg now belongs to a private collector.

3 Queen Elizabeth II Owns Three

The most important of Faberge collections belongs to the British Royal Family. Included in the vast collection are three of the historic eggs. Queen Elizabeth II’s grandmother Queen Mary bought the Colonnade Egg Clock, the Basket of Flowers Egg, and the Mosaic Egg. Perhaps the most beautiful is the one that resembles a flower basket; the beautiful blooms still look fresh and remarkably lifelike. The British collection is significant because many of the 100-plus masterpieces were either acquired directly from Faberge or arrived as gifts from family who also got them straight from their creator. It is also one of the biggest Faberge collections in the world, containing exquisitely delicate hardstone flowers, ornate boxes, figurines, photo frames, miniatures, and the largest assembly of Faberge hardstone animals and flower studies. Despite the size of the British collection, it’s a pittance to what the master goldsmith produced in his workshop. During his lifetime, Faberge produced around 200,000 pieces of distinctive jewelry and art.

2 The Kelch Family

Another patron Faberge served at the same time as the Imperial Romanovs was the Kelch family. Alex Kelch was a wealthy industrialist who commissioned seven eggs for his wife during their marriage. They rivaled the Imperial eggs in beauty, ingenuity, and, of course, their precious stone extravagance. All of the Kelch eggs were made by Faberge’s head workmaster, Michael Perchin, including one of the biggest eggs ever produced by the label—13.4 centimeters (5.3 in) in length. However, with the exception of the Apple Blossom Egg and the Pine Cone Egg, their designs were not wholly unique and often bore a resemblance to the royal eggs. When the couple divorced, Mrs. Kelch took her Faberge set with her to Paris. Six eventually ended up in the United States and—perhaps due to the flawless craftsmanship—half were misidentified as Imperial eggs. It was only in 1979 that all seven were correctly identified as belonging to the Kelch collection.

1 They’re Back

After the Revolution, the Faberge brand was sold a few times. Sadly, the famous name was used to tote toilet cleaner, shampoo, and cologne. The last company to acquire it, Pallinghurst Resources, mercifully decided in 2007 to return it to its illustrious origins and once again create spectacular pieces deserving of the Faberge name. Two years later, with the help of two of Peter Faberge’s granddaughters, Sarah and Tatiana, the world saw heavenly jewelry from Faberge for the first time since the Russian Revolution. Earrings, bracelets, and rings befitting of royalty were unveiled. Naturally, each demanded a small ransom. The crowning collection of the launch was the bijou egg pendants. Twelve in all, their designs have roots in the Imperial eggs themselves. Like the famous Easter eggs, their creation took a long time and groundbreaking craftsmanship to complete. While there will never be true Russian Imperial eggs again, the pendants will be widely available and cost between $8,000 and $600,000. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages