10 Nadine Haag’s Second Note

On December 4, 2009, Nadine Haag was found dead in her shower. The 33-year-old Australian woman had a deep cut on her wrist. Nearby was a razor, along with bottles of painkillers. There was also a note left on the side of the nearby spa bath. “My family—it hurts, it hurts—please live like there is no 2moro ever ever ever . . . Thank you for being beautiful creatures of this world. Thank you for looking after me.” Police and the local coroner declared that Nadine had killed herself. Yet Nadine’s family, especially her sisters, believed she’d been murdered. At the time of her death, Nadine had been in a heated custody battle with her ex-partner Nastore Guizzon, and the sisters suspected that he was responsible. Nadine’s sisters refused to let up pressure on the police. Eventually, they reached the detective in charge of the case, Julia Brown, who revealed that a second piece of paper had been found beneath the suicide note. The police had dismissed this as “just scribble.” The sisters insisted on seeing it, and when it was unfolded, the words jumped out to them: “HE DID IT.” The crime scene officer who had collected the note had read the message as “HEADED IT” and put it with the other unimportant evidence. Later, the new residents of Nadine’s flat found the same words etched into a tile near where she had been found. On the basis of the notes, New South Wales state coroner Paul MacMahon overturned the suicide verdict in 2013. He said he believed “Guizzon had a motive to harm Nadine, had the opportunity to do so, and lied about his whereabouts on 3 and 4 December 2009.” He has called for a full investigation.

9 The 98 Rock

Pearl Harbor was not the only US base attacked by Japan in December 1941. Japanese forces also advanced on Wake Island, a small coral Pacific atoll home to 1,600 American troops and civilian contractors. Japan captured the island by December 23. Most of the POWs were shipped to prison camps in China, but 98 remained. In 1943, the US struck back. On October 7, after two days of attacks, the Japanese knew they faced defeat, and they decided to execute the prisoners rather than let the US free them. The prisoners were lined up, blindfolded, and hit with machine guns. One of the captives, whose identity remains unknown, managed to escape and hide. In his last moments, he created a makeshift memorial. He carved the following inscription into a large coral rock near what would become the mass grave for him and his fellow victims: “98 US PW 5-10-43.” When the runaway was discovered, the Japanese admiral in charge of the island beheaded him personally. But the man was successful in his attempt to ensure that the fate of the 98 wasn’t forgotten. The rock is still there today.

8 The Touchingly Polite Immigrants

In May 2006, a yacht was spotted drifting 112 kilometers (70 mi) off the coast of Barbados. Rescuers sailed out to meet the craft, which was clearly in trouble. Unfortunately, they were much too late. The rusting vessel was home to 11 young men’s partially petrified bodies. Despite being found in the east Atlantic, the boat had set off from the eastern coast of Africa four months earlier, bound for the nearby Canary Islands. The men had each paid $1,800 for the opportunity to be smuggled into the Spanish territory. At least 40 other people had been with them at first, but they’d fallen victim to the ocean. When the desperate men realized something had gone wrong, some of them wrote their final letters to the world. One note read: “I would like to send to my family in Bassada a sum of money. Please excuse me and goodbye. This is the end of my life in this big Moroccan sea.” Another said: “I need whoever finds me to send this money to my family. Please telephone my friend Ibrahima Drame.”

7 The Hamstead Colliery Miners

On March 4, 1908, a fire broke out in the English Hamstead Colliery mine, trapping 25 miners underground. Their colleagues tried to reach them, but the fire was too much for them, and rescue teams with professional breathing apparatus fared no better. All 25 men trapped in the mine died. One of the rescuers, John Welsby, also died—due to heatstroke. When rescuers found the bodies a week later, they saw the dead men huddled together in four groups. One group of six men had left a last plea for salvation on a wooden board nearby. “The Lord Preserve Us,” began the message. It ended with: “For We Are All Trusting in Christ.” Between the two lines were the six miners’ names.

6 The Messages On Divers’ Slates

When underwater, divers communicate with one another by writing on slates with chalk. Since diving can be a dangerous activity, some of these slates inevitably end up carrying some divers’ final words. The most famous of these messages was written by Tom and Eileen Lonergan. The American couple were abandoned and forgotten by a tour boat off the coast of Australia in 1998, and their story went on to be immortalized in the film Open Water. A slate was later found with the following plea: “To anyone [who] can help us: We have been abandoned on A[gin]court Reef by MV Outer Edge 25 Jan 98 3pm. Please help us to rescue us before we die. Help!!!” However, not all diving deaths are as unusual or well known. The cave systems of North Central Florida have claimed hundreds of lives from inexperienced cave divers. Among those to die there was Bill Hurst, a diving instructor. He failed to return from a dive in 1976, and a recovery team later found his body. On his slate was a simple message: “I got lost. Tell my wife and kids I love them very much. ”

5 Bill Lancaster’s Fuel Card

Aviation pioneer William Lancaster crashed in the Sahara Desert on April 12, 1933 while trying to claim the speed record for a flight from England to Cape Town. It would be 29 years before anyone read his final words. His fate had been almost sealed before he’d taken off. He’d flown just a couple of hours in the previous year, after spending three months in jail for a murder charge. He was acquitted but had a breakdown, which kept him on the ground. Yet when he was deemed ready to fly again, he decided to go straight for a difficult record. After leaving England, he met unfavorable winds and had to stop off in Barcelona. To make up time, he ended up flying at night and got lost several times over North Africa. He had no cockpit light, so he had to use his flashlight every few minutes to check his compass. When he finally refueled in the Algerian town of Reggan, he’d been awake for 30 hours and could barely walk. Authorities tried to stop him from leaving, but he wouldn’t be persuaded. He was 10 hours behind schedule at that point, and if he delayed any further, he stood no chance at getting the record. Around an hour later, off-course, he crash-landed in the Sahara. It was 1962 when a French army patrol found the wrecked plane. With it was a fuel card on which Bill had written his final message. “So the beginning of the eighth day has dawned. It is still cool. I have no water . . . I am waiting patiently. Come soon please. Fever wracked me last night. Hope you get my full log. Bill. ”

4 The Battlefield Wills Of The British Army

At the start of the 20th century, the British Army’s standard equipment included forms for writing wills. Many superstitious young men, however, didn’t want to tempt fate by filling one out. So many soldiers, upon being shot and realizing they weren’t going to make it, would scrawl out their desires at the last moment. In one instance, a soldier in Afghanistan was found with the words “I want mother to have all” written on a rock in his own blood. While most weren’t that gruesome, these last testaments were hurried, short, and random. Among the items soldiers used were old envelopes, playing cards, and the edges of torn scraps of newspaper. Wills were carved into bayonet scabbards and scratched onto helmets with bullets. One soldier in World War I wrote his will on his glove. In almost every case, the soldier’s belongings were pledged to his mother or his sweetheart. Lieutenant Joseph A. Child simply wrote “I leave her all” when he was shot in 1918 during the First World War. The “her” in question was identified because he’d written the note on the back of a photograph of his wife. Some soldiers had the time to make their messages longer, such as “I leave everything to my beloved wife.” Some weren’t as lucky, and one man was only able to manage three short words: “all for wife.” One newspaper reported in 1915 that the workload for lawyers at London’s Somerset House had tripled because of the unusual wills they needed to process.

3 The Kursk Submarine Disaster

On August 12, 2000, the Russian nuclear submarine Kursk was on an exercise in the Barents Sea. For reasons that aren’t fully known, an explosion blew a hole in the submarine, and the vessel began to sink. Shortly afterward, its remaining torpedoes exploded. The submarine hit the seabed. What followed was one of the most botched rescue efforts in modern history. The Russians initially refused help from other countries, but after five days of failed attempts to reach the sub, Vladimir Putin relented. A Norwegian rescue ship and a British submersible rescue vehicle arrived within two days, and they reached theKursk on August 20. By then, it was much too late, and all 118 men on board were dead. Those sailors who’d survived the initial explosions had gathered in a rear compartment. One of the officers, Dmitry Kolesnikov, used the time to write a note. Four hours after the explosion, he began: “15:45. It’s too dark to write, but I’ll try by touch. It seems there is no chance, 10-20%. We hope that at least someone will read this.” Later in the note, he wrote that the survivors would “try to get out.” The final piece read: “Hi to everyone. Mustn’t despair.” Further lines were addressed to his family but were not released to the public. When the bodies were all finally recovered and buried, the note was displayed beside Kolesnikov’s coffin.

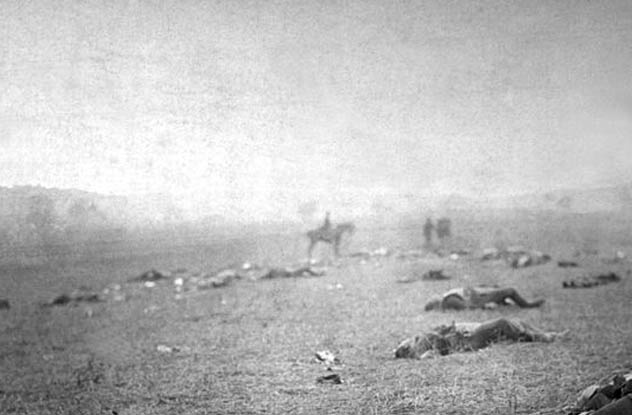

2 Isaac Avery’s Note To His Father

The battle of Gettysburg, with 50,000 casualties across both sides, was the deadliest and most important in the American Civil War. The address of Abraham Lincoln that came afterward is perhaps the most iconic speech ever made by a US president Isaac E. Avery was a colonel in the Confederate States Army. During the battle, he was shot in the neck and was partially paralyzed, unable to move his right arm. When the mortally wounded Avery was dragged from the battlefield, he was clutching a small piece of paper. He’d been knocked from his horse and had taken a piece of pencil lead from his pocket. Though right-handed, he’d used his left hand to scribble a note that read: “Major, tell my father that I died with my face to the enemy. IE Avery.” He died the following day in the hospital. The note is preserved in the treasures collection of the North Carolina State Archives.

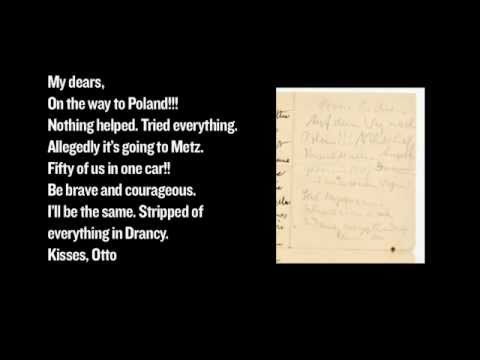

1 The Final Letter Of Otto Simmonds

Otto Simmonds was a German-born Jew who was captured by the Nazis in France. He was held at Drancy, a deportation camp in northeastern Paris that handled 70,000 prisoners over the course of the war. In August 1942, Otto was loaded onto a train bound for Auschwitz. It was there that he wrote a letter to his family. No one knows where he got the paper, pencil, or envelope. Watch this video on YouTube My dears, On the way to Poland!!! Nothing helped. Tried everything. Allegedly it’s going to Metz. Fifty of us in one car!! Be brave and courageous. I’ll be the same. Stripped of everything in Drancy. Kisses, Otto He threw the letter out of the train window. Amazingly, it was found by a railway worker, who forwarded it to Otto’s wife, Marthe. Marthe continued trying to find her husband into the 1960s, but he was never seen again. The letter became the only thing she had left to remember him by. Otto’s family donated the letter to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2010.

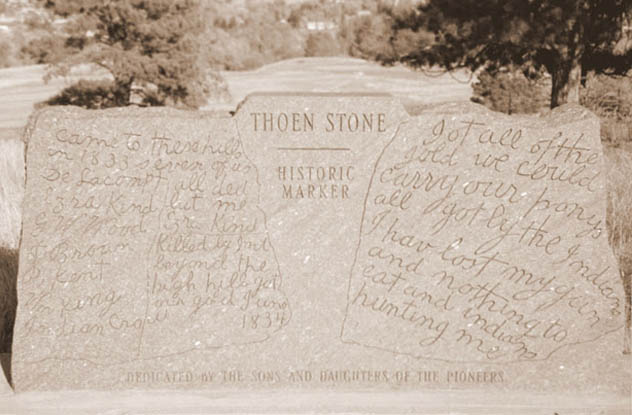

+ The Thoen Stone

In 1887, a stonemason named Louis Thoen made a discovery in the Black Hills of South Dakota. It was a sandstone slab, and it was inscribed with a message that read: Came to these hills in 1833 seven of us all died but me Ezra Kind killed by Indians beyond the high hill got our gold June 1834 The back of the stone had a further inscription: Got all of the gold we could carry our ponys all got by Indians I have lost my gun and nothing to eat and Indians hunting me. Many people believed it to be a hoax. After all, why would the unfortunate Ezra Kind have bothered to carve a message into stone? And wasn’t it convenient that it had been found by a mason? Yet the story was given some credibility when Ezra and his colleagues were found out to have been real people who went missing in the 1830s. The original stone is in a nearby museum. There’s also a replica where the stone was found originally. Whether it was real or a well-researched hoax created in the 1880s, it became a fascinating piece of history. Alan may have got something in his eye a couple of times while writing this list. You can tell him he’s a wuss on Twitter.