10Thomas Huxley vs. Richard Owen

During his career, Richard Owen had his fair share of notable achievements, among them coining the word “dinosaur” and founding the Natural History Museum in London. However, his relationships with his peers had always been strenuous. Nowadays, Owen is regarded as jealous and petty toward his colleagues, even plagiarizing their works on occasion. His rivalry with Gideon Mantell was probably his most bitter feud, but his rivalry with Thomas Huxley was much more beneficial for the scientific community. Huxley was known as “Darwin’s Bulldog” for his staunch support of evolution. Owen, on the other hand, was not onboard with Darwin’s theory, particularly the whole “man related to apes” bit. He sought to prove that humans and other primates, particularly the gorilla, were nothing alike by studying their brains. Huxley claimed the opposite and managed to prove it by discovering the hippocampus minor (now called the calcar avis) in apes, a part of the brain Owen had previously asserted only existed in humans. The controversy became known as the Great Hippocampus Question. Even though it was an easy target for humorists and newspapers, it shined a spotlight on evolution. The scientific community considered that Huxley handily won the battle and accepted evolution as the leading theory. The matter would be explored further in prominent publications such as Charles Lyell’s Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man and Darwin’s own follow-up The Descent of Man.

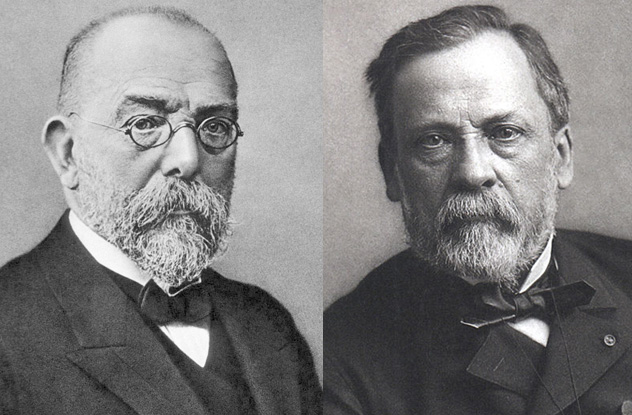

9Robert Koch vs. Louis Pasteur

Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur were instrumental to the development of the field of microbiology, not to mention the acceptance of germ theory. However, their contradicting opinions led to a public rivalry. The backdrop to this rivalry was the Franco-Prussian War, so nationalist sentiments most likely exacerbated their feud. By the 1870s, Pasteur shifted his attention to specific diseases instead of general processes like fermentation and putrefaction. As it happened, he focused on anthrax, a disease also studied by a young German doctor named Robert Koch. Initially, this overlapping interest didn’t cause problems. Koch focused on identifying and isolating the microbes responsible for the illness, while Pasteur was looking into immunization. The two eventually met at a medical congress in London in 1881, where their encounter appeared to be friendly. However, it wasn’t long until Koch and his German followers started finding faults in Pasteur’s work. Supposedly, when Pasteur organized a meeting to address his critics, the rivalry was exacerbated by a simple case of mistranslation. When Pasteur said “recueil Allemand” (“German work”), someone translated it to Koch as “orgeuil Allemand” (“German arrogance“). Over the next years, a game of one-upmanship would develop between the two, each one eager to show up the other. This rivalry turned out to be quite beneficial for mankind. Pasteur would discover a vaccine for rabies, Koch would identify the cause of tuberculosis, and each man would found one of the premier medical research institutes in the world.

8Humphry Davy vs. Michael Faraday

Here, we have a tale of two renowned chemists, a classic example of the student surpassing the teacher. Humphry Davy was one of the most acclaimed scientists of his day. He discovered several earth metals, invented the Davy lamp to use in mines, helped discover chlorine and iodine, and also developed uses for nitrous oxide. However, his achievements would soon be overshadowed by his student, Michael Faraday, who became a pioneer of electrochemistry. Faraday had almost no formal education when he became an apprentice. However, he was very keen to study chemistry and often attended lectures on the subject. Fortunately for the entire world, Davy saw something in Faraday and took him on as an apprentice despite his background as a bookbinder. Over the years, Faraday not only learned from Davy but also inherited some of his positive traits. Both men loved lecturing and passing on their knowledge to new generations. When he invented the Davy lamp, which became indispensable for miners, Davy avoided patenting it so more people would be able to benefit from its use. Like him, Faraday developed a disinterest in money and thought science should serve the public. Despite being knighted and receiving numerous honors, Humphry Davy was overshadowed by his former pupil’s accomplishments. On a few occasions, he criticized Faraday’s work and even tried to block his entrance into the Royal Society. However, his bitterness faded away toward the end of his life. When Davy was asked what his greatest discovery was, he simply replied, “Michael Faraday.”

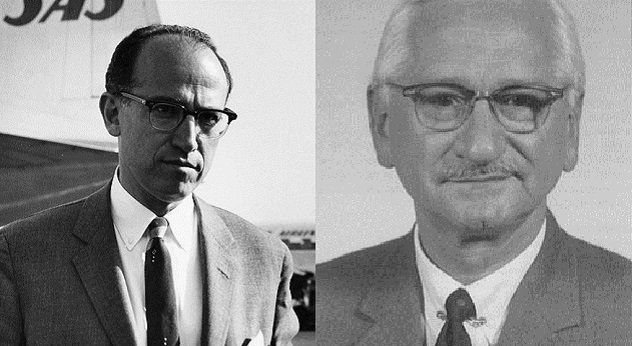

7Jonas Salk vs. Albert Sabin

This rivalry has never really been between the two scientists Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin. Rather, it was a competition between their life-changing creations—the polio vaccines. The men created their own versions of the vaccine only a few years apart (Salk was first). Ever since then, there has been constant debate regarding which vaccine to use. Both men have vocal supporters and critics, but their combined efforts have eradicated polio in many parts of the world. Sixty years ago, polio was a major health concern. The disease affected mainly children and could leave them paralyzed or even prove to be fatal. In 1955, Jonas Salk developed his polio vaccine to the cheers of a grateful nation. A few years later, Albert Sabin finished his own vaccine. There were some key differences between the two: Salk’s vaccine was injected, while Sabin’s was administered orally. Salk’s vaccine used a “killed” poliovirus, while Sabin used a “live” but weakened virus, believing that it was the only way to achieve long-lasting immunity. Salk’s vaccine was used initially but was eventually replaced by Sabin’s vaccine, which was the one used for mass worldwide inoculations. It hasn’t been proven conclusively that the oral vaccine is more potent than the injection, but people have argued that Sabin’s vaccine could actually cause infection if the virus is not weakened enough. In 1999, this persuaded the US to switch back to Salk’s vaccine, and the debate still rages on today.

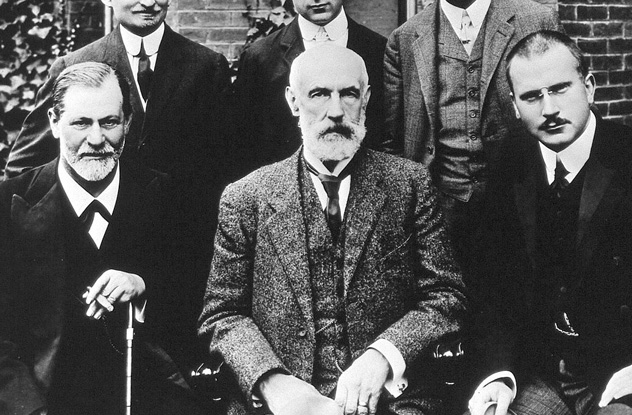

6Sigmund Freud vs. Carl Jung

As two of the most distinguished psychotherapists of all time, Freud and Jung enjoyed a love-hate relationship. When they first met in 1907, Freud was almost 20 years older than Jung. However, the two of them hit it off immediately, having a discussion that lasted 13 hours. They developed a strong friendship, but the age gap did make it seem more like a father and son relationship rather than two buddies hanging out. For the man who named the Oedipus complex, this could be disconcerting. Usually, it didn’t pose a problem. At times, Freud called Jung both his “adopted eldest son” and his successor. Sometimes, though, Freud had neurotic episodes that showed distrust in Jung. During one journey to America in 1909, Freud accused Jung of wanting him dead and then fainted. More problematic for Jung and Freud’s relationship were their professional differences. They disagreed on several subjects, including Freud’s core belief that sexual desire is our main drive in life. Jung believed that sexuality is just one of many components of the life force. Jung also believed that the unconscious mind was not a treasure trove of repressed memories like Freud did and was also a believer in parapsychology, while Freud was a staunch skeptic. The two had a falling out in 1912 after Jung published his Psychology of the Unconscious. Despite this, Freud’s influence remained obvious throughout Jung’s career, especially when the student started a new successful movement in psychology of dream analysis.

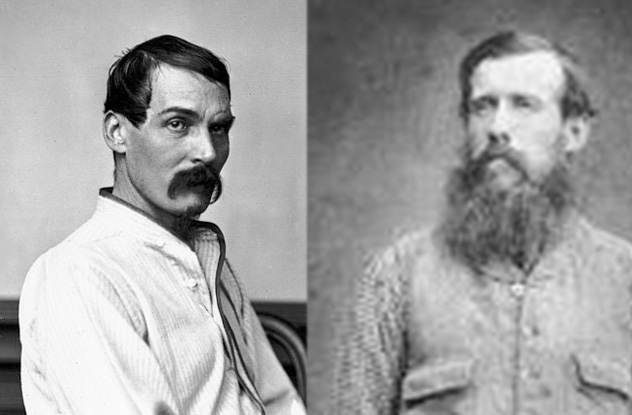

5Richard Burton vs. John Speke

Richard Burton and John Speke were two Victorian explorers and geographers who became famous for their quest to find the source of the Nile. The two men traveled to Africa in 1856 with very little information to go on other than looking for a great lake around the mountainous region known back then as the Mountains of the Moon. Right off the bat, Burton and Speke didn’t have a great working relationship. The two men simply had clashing styles: While Burton was a recluse who spent most of his time studying books, Speke was out hunting with the local guides. In 1858, the two men became the first Europeans to reach Lake Tanganyika. Although they initially considered it a potential source for the Nile, the two eventually dismissed it because Tanganyika had a river flowing in rather than out. Illness prevented Burton from going forward, but Speke carried on and eventually found Lake Victoria, which he classified as the source of the Nile. The rivalry between the two explorers escalated upon arrival in England, when Speke supposedly tried to take sole credit for the discovery by presenting it by himself instead of waiting for Burton as agreed. This started Burton on a bitter path to discredit his former partner. This quest was successful mostly because Speke died a few years after the trip in a hunting accident. However, a later expedition by Henry Morton Stanley did prove that the two explorers discovered the source of the Nile, whether they’d liked it or not.

4Gilbert Lewis vs. Walther Nernst

Like Davy and Faraday, Walther Nernst and Gilbert Lewis were, at one time, teacher and student. In 1900, after already establishing himself as one of the greatest chemists of his day, Lewis left his teaching position at Harvard to pursue a fellowship with one of the pioneers of physical chemistry, Walther Nernst. However, while working at his lab, Lewis developed quite a dislike for Nernst that haunted the rest of his professional career. In 1920, Walther Nernst won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on thermochemistry. Two years later, Lewis was nominated for the same award but didn’t win. He was nominated again in 1924 and 1925 and, in fact, in most of the years that followed. By the time his career was finished, Gilbert Lewis had been nominated for a Nobel Prize in Chemistry 35 times and didn’t win once. This was mostly due to Lewis’s tendency to make powerful enemies. His dislike of Nernst caused Lewis to criticize him whenever he had the chance, often using extreme hyperbole to denounce his former teacher. In one instance, Lewis called out Nernst’s calculations, naming them “a regrettable episode in the history of chemistry.” This didn’t sit well with many academics who supported Nernst, particularly former Nobel laureates and Nobel Prize committee members. Lewis and Nernst might have revolutionized the field of thermodynamics, but their rivalry ensured that only one of the men received the recognition he deserved.

3Francis Crick vs. Maurice Wilkins

Discovering the structure of DNA was no easy feat. In fact, it took two teams over a decade before they finally figured things out. In one corner, we had Francis Crick and James Watson from the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge. In the other, we had Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins from King’s College London. To make matters worse, Franklin and Wilkins didn’t really get along. Nowadays, it’s generally known that Crick and Watson were the ones who figured out the double helix structure. However, newly discovered correspondence between Crick and Wilkins suggested that there was quite a fierce rivalry developing between the two. At one point, Crick and Watson visited their competitors in London. After hearing Franklin talk about her latest results, they returned to Cambridge. There, they got to work on a DNA model based on her data with one fatal flaw—it had a triple helix. What they had done wasn’t really stealing, as the London researchers had freely shared their findings, but it did create a sense of competition in both teams. Even so, this didn’t stop Wilkins from writing Crick a letter, politely asserting how “bloody browned off” he was with their theft. Crick was jovial in his reply, saying that even though they “kicked (them) in the pants, it was between friends.” In the end, Franklin left the laboratory, while the other three continued their work. In 1962, the three men shared a Nobel Prize for discovering the molecular structure of DNA.

2Robert Hooke vs. Isaac Newton

We often say that history is written by the victor, and perhaps this is best evidenced by Robert Hooke. By all accounts, Hooke was a renowned, respected scientist whose numerous contributions should have ensured his place in history. However, at one point, he almost became completely forgotten because Hooke was on the losing side of a bitter rivalry with one of the most famous people in history: Isaac Newton. Even today, we find it difficult to judge with certainty the relationship between the two men. Some say that Hooke was a bitter man jealous of someone more intelligent and more successful than him. Others claim that Newton took great exception to Hooke’s criticism regarding one of Newton’s early papers on optics and later used his position as President of the Royal Society after Hooke’s death to minimize his contributions as much as possible. A series of letters between the two men lends credence to both positions. The biggest bone of contention between Hooke and Newton was the latter’s law of gravitation, one of the most famous laws in all of physics, outlined by Newton in his iconic work Principia Mathematica. Hooke always maintained that Newton took the idea of an inverse-square law from him, and he might be right. Other people worked on a universal law of gravity before Newton, including Hooke. Newton acknowledges them in passing in his book, but Hooke considered that his contribution to an essential law of physics might have been worth a little more.

1Edward Drinker Cope vs. Othniel Charles Marsh

Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh were two American paleontologists who were responsible for one of the most productive (and, at the same time, one of the most embarrassing) periods in paleontology. Their epic rivalry became colloquially known as the Bone Wars and formed the basis for numerous books, a documentary, and even a graphic novel. There were many differences between the two. Cope came from a rich family, while Marsh was working-class. They had contrasting personalities and different scientific approaches to their work. So, even at the best of times, their relationship wasn’t going to be very cordial. However, their rivalry was born when Cope presented his reconstruction of his then-crowning achievement—the Elasmosaurus. Marsh publicly humiliated Cope when he pointed out that Cope put the dinosaur’s head at the wrong end. Nowadays, we are all familiar with dinosaurs with very long necks, but back then, this wasn’t common, so Cope naturally assumed the long end was the tail. From this moment on, the two men began a game of one-upmanship, never shying away from any underhanded tactic to gain an advantage. They would criticize each other in the press, sabotage dig sites, and even bribe workers to steal specimens. Despite their shady dealings, Cope and Marsh discovered and described over 100 species of dinosaur. However, due to carelessness, only about 30 are still valid today. Even so, their exploits brought a lot of attention and interest in dinosaurs and prehistoric life in general. Follow Radu on Twitter.