From sticks and stones and other traces of ancient life, archaeologists have gleaned fascinating new information about what our ancestors ate, which unexpected diseases plagued them, how they reared their children, and how they entertained themselves.

10 The Ancient Chinese Ate ‘Ice Cream’

Thanks to a little chemistry trick, the Chinese were enjoying frozen confections almost 3,000 years ago. They saw that minerals reduce the freezing point of water by observing that melting saltpeter in water can cause it to freeze under certain conditions. Around 700 BC, they put the discovery to culinary use, making a slushy, icy mixture of honey, milk, and/or cream.[1] Ancient ice cream knowledge spread to Persia about 2,500 years ago. The Persians added fruit or floral flavors, like rose, to the already-sweet treat. They called it sharbat, Arabic for “fruit ice,” which is where the term “sherbet” comes from.

9 People Suffered From Excruciating Prostate Stones

Archaeologists found three mysterious ovoid rocks next to a prostrate skeleton at the ancient Al Khiday cemetery in Sudan. They decided that the stones weren’t placed there as a burial offering and hadn’t found their way there by some geologic coincidence. Instead, they originated from the man’s body while he was alive. From his prostate, specifically. Like kidney stones, the man’s walnut-sized prostate stones were the result of accumulated calcium inside the prostate. In current times, they require surgery, so the man likely suffered quite a bit. The discovery rules out prostate stones as a modern disease and shows that people have been afflicted with such conditions for at least 12,000 years.[2]

8 Nasty Parasites And Worms Traveled The Silk Road

The Silk Road routes allowed a great exchange of goods between Asia, Europe, and Africa, but they may have also been a pathway for diseases. Recently, archaeologists found the first direct evidence of this at the Xuanquanzhi rest stop in Dunhuang, China. The researchers found some 2,000-year-old toilet wipes in the form of pieces of cloth wrapped around sticks. Luckier still, the wipes maintained traces of feces even after two millennia, thanks to the arid conditions. Analysis revealed that the unknown pooper suffered from parasites, including whipworms, tapeworms, roundworms, and Chinese liver flukes, which must have originated 1,500–2,000 kilometers (925–1,245 mi) away.[3]

7 Women Traveled From Afar To Start Families

German archaeologists studied 84 skeletons buried between 2500 and 1650 BC, a period that segued between the Stone Age and the Bronze Age. They discovered that most of the women had traveled at least 500 kilometers (300 mi) to start their families.[4] On the other hand, the men had died close to where they were born. This “patrilocal” trend was consistent throughout the late Stone Age and early Bronze Age. The discrepancy suggests that the gender roles we associate with ancient people require some tinkering. Women weren’t always confined to the home while the men traveled, traded, and pillaged. The womenfolk wandered to faraway locales, spreading ideas, sharing culture, and starting families.

6 The Romans Built Huge Libraries

A construction project in Cologne revealed a Roman wall, which researchers pegged as part of an assembly hall before they noticed a series of curious niches within it. Turns out they found Germany’s oldest library. The region was settled by the Romans in 38 BC. It received Roman amenities like aqueducts, walls, sewers, and cultural enrichment in the form of mosaics and said library, which was erected in the second century.[5] The 1,800-year-old library was two stories tall and filled to the brim with at least several thousand parchment scrolls and maybe as many as 20,000. The volumes were compiled by Roman curators and, like current-day propaganda, may have been censored or chosen due to bias.

5 The Armenians Made Wine In Gigantic Vats

The people of modern-day Armenia are expert winemakers thanks to more than six millennia of practice. Some Armenian families still own a relic from the region’s viticultural past, a gigantic 910-liter (240 gal) clay vessel called a karas. They’re no longer produced in Armenia, but these huge containers once held fermenting wine, like archaic varieties that occasionally included human blood. These people really loved their wine as shown by the discovery of a cellar filled with hundreds of karases that held 380,000 liters (100,000 gal) of wine. The karases that weren’t lost to history or used as coffins (seriously) can still be found in people’s basements and storerooms because they’re too large to move without demolishing either the karas or the doorway.[6]

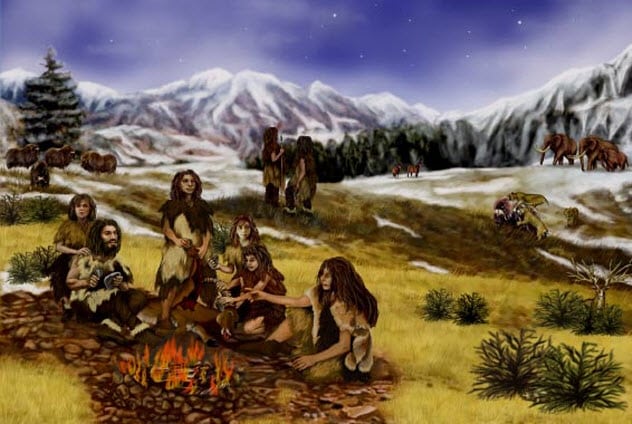

4 ‘Cavemen’ Used Clever Tricks To Make Fire

New research shows that Neanderthals didn’t rely on lightning to supply fire; they could make their own. Just like TV survivalists, the Neanderthals bashed a chunk of flint against some pyrite to create sparks. In the process, they made a significant mental leap by realizing that some dull, inert rocks could birth something as dynamic as fire. Another 50,000-year-old piece of evidence from the tongue-twisting Pech-de-l’Aze I site in France suggests that Neanderthals were even cleverer. Scientists unearthed blocks of manganese dioxide that exhibited signs of abrasion. When the researchers ground the substance into powder, they found that it reduces wood’s combustion point from 350 degrees Celsius (662 °F) to 250 degrees Celsius (482 °F).[7]

3 Ancient People Loved Boxing

Humans have always fancied a good fistfight. Boxing originated at least 5,000 years ago in Egypt, became an Olympic sport in Greece in 688 BC, and then was adopted by the Roman army as a fitness-boosting martial exercise. From there, it became a favorite spectator sport, and competitions were held, with all the cussing and gambling you’d expect. Archaeologists have historical accounts as well as bronze statues depicting boxers, and now they’ve found an actual pair of 1,900-year-old gloves at Vindolanda Fort in England. They’re cut from leather and filled with natural material for shock absorption. But they look more like knuckle guards than actual gloves. They might have been sparring gloves, as the ones used in competition packed a lethal metal edge.[8]

2 Humans Put Dogs On Leashes Around 9,000 Years Ago

According to Holocene-era (12,000 years ago to present) etchings, we’ve been keeping dogs on leashes for nearly 9,000 years. Discovered at two sites in Saudi Arabia, the etchings are possibly the oldest images of domesticated (i.e., leashed) dogs. In one picture, we see a hunter and a pack of dogs, some of them apparently leashed, going after horselike creatures. (Researchers say the canines resembled modern Canaan dogs.) It’s a surprisingly sophisticated anthro-canino relationship. The image suggests that dogs might have been bred, trained, and organized into large groups (one etching included 21 dogs) to assist their masters in taking down big prey.[9]

1 Children Accompanied The Family On Hunts

Archaeologists can piece together complex scenes from scant evidence. In fact, they have extrapolated the child-rearing practices of Homo heidelbergensis (a modern human predecessor) based on 700,000-year-old footprints. Normally, they erode quickly, but the ones at the Melka Kunture site in Ethiopia were preserved by a volcanic ash flow. The small prints likely belonged to children as young as one or two years old. Researchers also found the adults’ tracks as well as those of various animals, all centering around a small watering hole.[10] Butchered hippo remains and stone butchering tools were also discovered, completing this moment frozen in time. It suggests that children were not left at home but brought along on dangerous errands like hunts, probably so that they could observe and begin learning these skills for themselves.