10 Seasonality And War

During the Romans’ early history, the logistical challenges of conducting a war meant that the Romans only fought between sowing and harvest (during the summer). Rome was an agriculture-based economy, and the movement of troops during winter was highly demanding. According to Livy (History of Rome, 5.6), if a war was not over by the end of summer, “our soldiers must wait through the winter.” He also mentioned a curious way that many soldiers chose to spend the time during the long waiting: “The pleasure of hunting carries men off through snow and frost to the mountains and the woods.” The first recorded continuation of war into the winter by the Romans took place in 396 BC during the siege of the Etruscan city of Veii.

9 Decimation

Mutiny of the troops was always a potential issue for Roman generals, and there were many policies in place to discourage this type of behavior. Punishment by decimation (decimatio) was arguably the most feared and effective. It involved the beating or stoning to death of every 10th man within the army unit where mutiny took place. The victims were chosen by lot by their own colleagues. Whenever a group within the army was planning a mutiny, the prospect of decimation made them think twice and they were likely to be reported by their own colleagues. The Romans knew that decimation, although effective, was also unjust because many of the actual victims might not have had anything to do with the mutiny. From the standpoint of the Romans, the unfairness of decimation was a necessary evil. Tacitus (Annals 14.44) wrote, “Setting an example on a large scale always involves a degree of injustice when individuals suffer to ensure the public good.” (McKeown 2010: 40-41)

8 Property Qualification

Military service was both a duty and a privilege of Roman citizens. In its early days, the Roman army was composed exclusively of citizens and organized on the basis of their social status (according to the weapons and equipment they could afford). The richest served in the cavalry, those not so rich served in the infantry, and men without property were excluded from the army. After the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), this recruitment system became obsolete. Rome had become involved in longer and larger wars, and they needed a permanent military presence in the newly conquered territories. The property qualification was therefore reduced. During the second century BC, property qualification was reduced even more. Then, in 107 BC, Gaius Marius began to accept volunteers who had no property and were equipped at the expense of the government. (Hornblower and Spawforth 2014: 79)

7 Siege Warfare

Whenever a town or building was under siege, a special army unit was sent ahead to surround the settlement and prevent anyone from escaping. A fortified camp would then be established around the area, preferably on high ground and always out of missile range. An army unit would then be sent to breach the defensive walls, protected by covering fire from archers, bolt-firers, and catapults. The catapult was one of the most intimidating siege weapons. Josephus (The Jewish Wars, 3.7.23) offers us a firsthand account of the catapult’s devastating power: “A soldier standing on the wall near Josephus was struck by it [a stone thrown by a catapult]. His head was torn off by the stone missile, and the upper part of his skull was hurled [550 meters (1,800 ft)].”

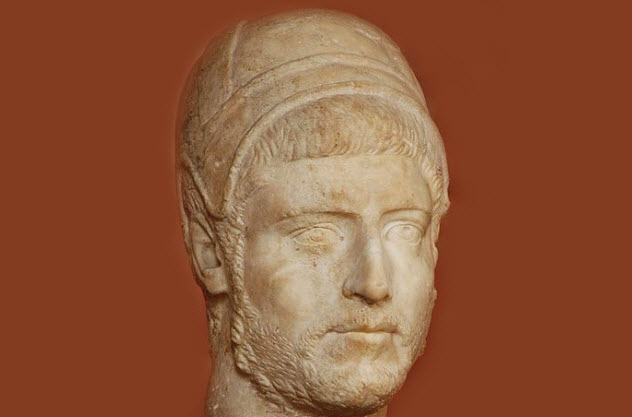

6 Tunneling

Tunneling was key for siege warfare. The failure or success of many sieges was decided by how well the Romans were able to breach the defensive walls by digging tunnels underneath the town or building in question and breaking in. Although this was an effective tactic, it became widely known to Rome’s enemies and eventually lost its surprise factor. During the war against Mithridates of Pontus in the early first century BC, the Romans were trying to dig a tunnel to breach the defenses of the city of Themiscyra. Its inhabitants drove a number of dangerous wild animals into the tunnel, including bears and even bees. The oldest archaeological evidence of chemical warfare has been dated to the third century AD and comes from tunnels found at Dura Europus (Syria), where evidence of an underground battle between the Romans and the Sassanian Persians were found. The Persians were besieging a Roman garrison and using tunnels to break in. The Romans responded by also digging tunnels to neutralize the attackers. Skeletons and weapons found in one of these galleries attest to the fact that the Roman soldiers were choked to death by an asphyxiating gas cloud coming from bitumen and sulfur crystals ignited by the Persians.

5 Helmet Function

According to some ancient writers, helmets in the Roman army had other benefits besides their obvious protective function. Polybius (Histories, 6.23) noted that the decorations on top of their helmets had a psychological impact on their enemies because it made the Roman soldiers look taller and more intimidating. The use of helmet decoration to intimidate enemies was widely practiced by most cultures. But in this case, Polybius was referring specifically to the use of a “circle of feathers” to make the Romans look considerably taller than they actually were. This observation makes sense when we consider that many of their enemies, especially in central Europe (e.g., Gauls and Germans), were much taller and robust than the Romans.

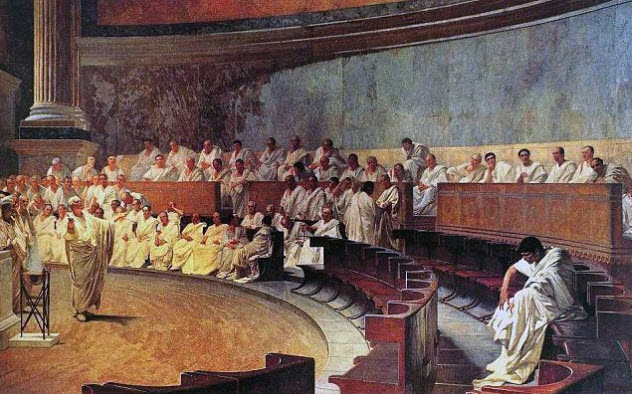

4 Decision-Making Process

During the times of the Roman Republic, only the Senate, considered the governmental entity that embodied the will of Roman citizens, was entitled to declare war. As Rome expanded and the power of its generals grew larger, some wars were declared by the Roman generals without senatorial approval. An example of this was the war against Mithridates of Pontus, which was declared in 89 BC by the consul and general Manius Aquillius without any involvement from the Senate. This was illegal in theory, but in practice, there was little the Senate could do. Some generals were just too powerful. When Rome became an empire, the decision of going to war became the emperor’s responsibility alone.

3 The Fetials

Rome had a specialized body of priests known as the fetials, whose sole obligation was to perform the rituals involved in going to war and making treaties. The final step in the ritual of declaring war was throwing a spear into the territory of the enemy. By the early third century BC, Rome had expanded significantly, covering almost all the Italian peninsula from the Po Valley to the South. Throwing a spear into enemy territory was no longer a convenient procedure for declaring war; the borders of Rome were too far away for the fetials to complete the ritual. Superstitions, however, don’t die easily, and the priests came up with a clever alternative. A portion of land not far from the temple of Bellona (the goddess of war) was declared to be non-Roman. At the time of the war against King Pyrrhus of Epirus (280–275 BC), an enemy soldier was captured by the Romans and forced to buy part of this land so that the spear could be thrown into it.

2 Gladius Hispaniensis

The standard short sword used by the Roman army was known as the gladius hispaniensis (“Spanish sword”), and it was developed in the Iberian Peninsula. Its lethal effectiveness and practicality were proverbial. According to Livy (History of Rome, 31.34), when the Romans fought against Philip V during the Macedonian War (200–196 BC), the Macedonians were shocked by the effects of the Roman sword: The Macedonians [ . . . ] had [so far] only seen wounds inflicted by spears and arrows. When they saw the bodies dismembered by the Romans’ Spanish swords, and arms sliced off at the shoulder, and heads separated from the trunk, neck and all, and entrails exposed, [ . . . ] they trembled as they realized what weapons and what soldiers they would have to face.

1 Donatives

The Praetorian Guard was a specialized unit of the Roman army that acted as household troops to the emperor and his personal bodyguards. During the first century BC, the Praetorian Guard occasionally got involved in the process of appointing new emperors. But as time went by, their involvement grew larger until they eventually got into a position where they were able to appoint, remove, and even murder Roman emperors. One incentive for murdering emperors and appointing new ones was a practice known as “the donative,” which was an economic reward that the Praetorian Guard received from the newly appointed emperor once the previous one was killed. This practice was one of the reasons why emperor succession became truly chaotic during the late history of the Western Roman Empire. Once the loyal protectors of the the head of the Roman government, the Praetorian Guard gradually and ironically turned into a corrupt and dangerous army unit that held significant control over the life of the emperors.

+Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article you should probably also take a look at these fascinating lists from our archives: Roman Life 10 Truly Disgusting Facts About Ancient Roman Life Top 10 Bizarre Ancient Roman Medical Treatments 10 Little-Known Aspects Of Ancient Roman Family Life 10 Lesser-Known Ancient Roman Traditions Violent Pursuits 10 Famous Gladiators From Ancient Rome 10 Cruel And Unusual Facts About The Colosseum’s Animal Fights 10 New Archaeological Clues About Roman Warfare Facts And Fictions Top 10 Myths About the Romans Top 10 Fascinating Facts About The Romans 10 Little-Known Facts About The Ancient Romans Read More: Twitter Facebook Ancient History Encyclopedia