10 The Daily Temple Ritual

To keep the universe running smoothly, a small army of holy men tended to the gods’ every whim with daily offerings across Egypt’s many temples. Each temple housed a particular god in the form of an enshrined statue that had gone through an “opening of the mouth” ritual to imbue it with the quintessence of a deity’s spiritual entity. These gods received the rock star treatment from priests of varying rank and allegiance who made daily offerings of food, drink, and gifts. The priests also sang hymns and even washed and clothed the gods. Ceremonies ranged in complexity. At Karnak, the daily procedure to venerate king-god Amun-Ra consisted of more than 60 formulae, or points of focus, including the application of oils, incense, and eye paint. There was also a yoga-like set of poses and strict guidelines for anointing the god-statue with kisses.

9 The Holy Colors

The Egyptians produced a variety of quality handicrafts, which found their way throughout the ancient world. Based on an unassuming blue bead found in the grave of an extravagantly buried Danish woman in Olby, some items made it to Scandinavia as early as 3400 BC. Plasma-spectrometry is used to detect the tiniest traces of elements without damaging the source material, and such analysis credits the beads to the Egyptian glass workshop at Amarna. In Egypt, blue symbolized the primeval sea from which creation bloomed. Abroad, glass fetched a high price and accompanied elite burials. In exchange, Nordic peoples sent back their abundant amber, another mystical substance due to its sunlike sheen. Representing the Sun’s glory, pieces of sacred amber were interred with many pharaohs. According to researchers, the intermingling of items may have even shaped spiritual beliefs in Scandinavia.

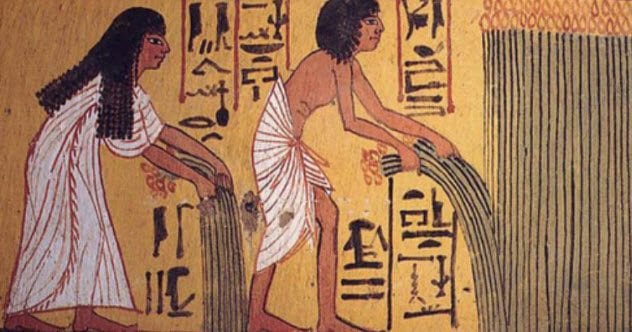

8 Workers Signed Their Creations

Egypt’s laborers and draftsmen often marked their monuments with a spot of personal graffiti, sometimes humorous, to brag about the amazing structure they had just raised. Thanks to informal graffiti records, researchers can piece together how workers tackled Egypt’s massive, man-crushing projects. First, they were organized by the thousands and then into smaller and smaller subdivisions, each assigned to a certain task. Each gang—they’re literally called “gangs”—of workers adopted a moniker and suffixed their signature with the name of the king. This produced whimsical team names like “The Drunkards of Menkaure.” This graffiti adorns tombs, pyramids, and other monuments. Some items bear different gang names on opposite sides, suggesting that the workforces competed in nonviolent gang wars to outbuild their peers.

7 Egypt’s Female Physicians

The ancient Egyptians were fairly keen on gender equality. Women enjoyed many liberties that disappeared in successive cultures, such as the right to own property (including slaves) and to execute legal documents. Furthermore, women were well respected in professions that have become much more male-centric in modern times, such as medicine. Records reveal at least 100 Egyptian female physicians, including history’s first named female doctor, chief physician Merit Ptah, who practiced nearly 5,000 years ago. Inscriptions on tombs tell of Peseshet, another great woman of similar renown. Peseshet was not only a physician but the overseer of physicians. As supervisors or clinicians, Merit Ptah, Peseshet, and other female doctors were much esteemed and ultimately immortalized in hieroglyphics.

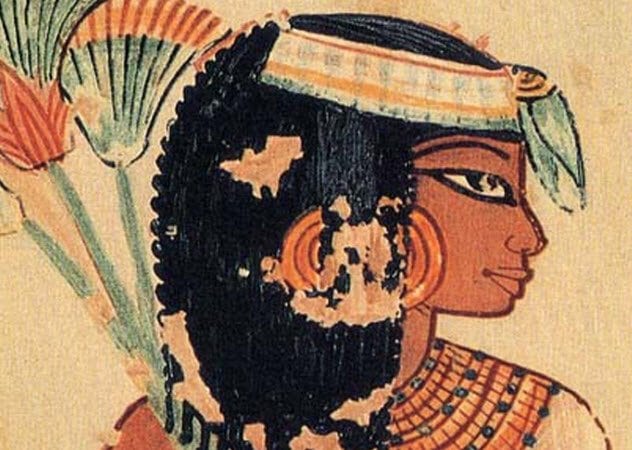

6 The Blue Water Lily

The blue water lily (aka Nymphaea caerulea) oozed religious significance. A creation myth asserted that a primordial water lily emerged from the unformed chaos of the pre-universe and spawned the Sun god, progenitor of all life. The flowers unfurl their petals each morning to display their golden centers before closing again in the afternoon. This daily cycle emulates that of the Sun. So the lilies are like tiny versions of the Sun god and the perfect sacred icon to ornament monuments and temples. Images also depict denizens holding the lilies to their faces, sniffing them, or consuming lily-laced wine. Shamans also used the lilies medicinally and ritually to attain trancelike states. More recent research shows that the lily and its brethren plants contain a vasodilating ingredient that can battle erectile dysfunction, possibly explaining its appearance in erotic art.

5 The Egyptian Diet

To find out what the Egyptians ate, French researchers analyzed the ratio of two carbon isotopes in 45 mummies from disparate time periods from 3500 BC to AD 600. Certain plants draw in the carbon isotope carbon-12, while others “prefer” the heavier carbon-13. Since animals also eat plants, the carbon variants can elucidate Egyptian meat consumption. As evidenced by the carbon makeup of their diets, which skewed vegetarian, the Egyptians noshed mainly on plants. Even though the Nile became increasingly arid, expert irrigation techniques provided plentiful plant-based foodstuffs. Primarily, Egyptians followed a carb-laden, wheat, and barley-heavy diet, supplementing it with a touch (less than 10 percent) of Old World starches like sorghum and millet. Despite all the textual and hieroglyphic evidence for fishing, the Egyptians surprisingly ate very little seafood.

4 Egyptian And Nubian Culture Mash-up

Discovered in former Upper Nubia, the tomb of a middle-class Nubian woman suggests that the Egyptian and Nubian cultures freely intermingled after the former conquered the latter in 1500 BC. According to researchers, the yet-to-be-deceased enjoyed the freedom to customize the burial they’d receive. For example, the aforementioned woman chose the funerary pupu platter. She was interred in an Egyptian tomb but eschewed the sarcophagus for a bed, a Nubian practice. Similarly, she forwent the traditional Egyptian mummification process. Instead, as per Nubian convention, she was placed on her side in a pose similar to the fetal position. Finally, she shunned the ivory death jewelry favored by her compatriots and is rocking an Egyptian amulet around her neck. The amulet is emblazoned with the image of Bes, the domestic protector-god.

3 Health Problems In The Capital

Hieroglyphs showing the Egyptian good life are lies. This was deduced from the human remains in a cemetery in Tell el-Amarna, the former capital under Akhenaton. He was the pharaoh who unsuccessfully attempted a permanent switch to monotheism and successfully fathered King Tut. The skeletons at the cemetery paint the average Egyptian capital-dwellers of more than 3,000 years ago as tinier and sicklier than expected. The collection of hobbit-sized bones revealed an average male height of 158 centimeters (5’2″) with females standing a few centimeters shorter. The skeletons also show signs of overexertion and a clinical want of protein. Bone fractures were common, as were spinal injuries from the grueling workload. Younger populations were plagued with stunted growth and high juvenile death rates, with 74 percent of the children and teens displaying anemia, an affliction apparent in 44 percent of the adult population.

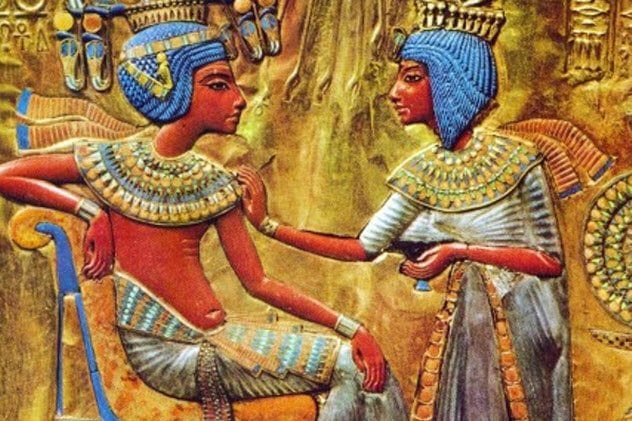

2 Marriage

Even though premarital sex was not considered taboo, a social expectation to marry existed. Egyptians did so at an early age, often before their 20th birthdays. However, the state and religion had no influence regarding any facet of marriage. Rather, Egyptian matrimony resembled a social contract that regulated property, with each member legally entitled to their premarital possessions as well as joint ownership of anything that the couple procured while married. Thanks to the egalitarian concept of Egyptian marriage, women could just as easily request a divorce as men—for just about any reason. In fact, women seem to have had the advantage. In female-initiated splits, the woman kept her possessions as well as up to two-thirds of the former couple’s joint property. Divorce was common. But many people remarried afterward because neither divorce nor remarriage was considered unacceptable. As bureaucratic as it all sounds, texts and images paint the Egyptians as a romantic, compassionate, monogamous people.

1 The Aphrodisiac Lettuce

On the list of historical aphrodisiacs, lettuce looks the most like a typo. The first tomb depictions of the leafy green date to almost 5,000 years ago. Somehow around 2000 BC, it took on a sexual significance and became the calling card of Min, the god of fertility. Supposedly, the imaginative Egyptians noted that lettuce stalks emerge from the ground straight and erect, resembling a certain part of the male anatomy. So they associated it with Min. Also, a chunk of lettuce cut at the base secretes a white, milky substance which the Egyptians likened to life-bearing liquids like mother’s milk or semen. Odder still, the Egyptians didn’t generally eat lettuce. They disposed of the bitter leaves and pressed the seeds, wringing out a healthful oil used for medicinal purposes, cooking, and even the preparation of mummies.