As is often the case, this event came about as much through chance as by any careful planning. If a few different choices had been made by either the Soviet Union or the United States, the history books could have looked very different.

10 Khrushchev Just Wanted A Missile

When Nikita Khrushchev became the Russian leader in 1953, he had a problem. The Cold War was at its height, and the Soviet Union felt very vulnerable. If real war ever broke out, American aircraft, carrying atomic bombs and flying from bases in Western Europe, could be over Leningrad and Moscow in a few hours. Soviet planes would take far longer to reach the United States. By the time they got there, the cities of the USSR were likely to be charred ruins. Khrushchev needed a new weapon, something that would stop the Americans from thinking they could win a war with a first strike. He needed a missile that could hit the US less than an hour after being launched. So in 1954, the go-ahead was given to develop the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile.[1] The man given the job of creating this weapon was Sergei Korolev. The new missile was designated the R-7, and it had to be big. Russian H-bombs were heavy. The R-7 needed to be capable of delivering a 3-ton warhead onto a target over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 mi) away. The Soviet missile was way bigger than anything the Americans were working on.

9 Korolev Wanted To Go Into Space

Like many men fascinated by rockets, Sergei Korolev dreamed about space exploration, and he realized that the R-7 would be powerful enough to put satellites into orbit. In 1956, designer Mikhail Tikhonravov put forward a proposal for a satellite that could be launched by the R-7, and in September, Korolev got permission to go ahead with the project.[2] The plan was to launch the satellite during the International Geophysical Year, which ran from July 1957 to the end of 1958. For Khrushchev, though, the satellite was a minor distraction. He needed a missile that could hit the US; nothing else really mattered.

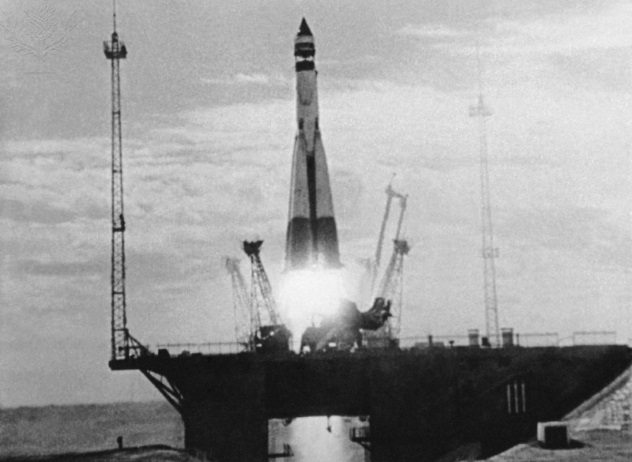

8 The Heat Shield Failed

The first launch of the R-7 took place on May 15, 1957. The missile crashed after traveling just 400 kilometers (250 mi). The next flight, a month later, only lasted 33 seconds. Modifications were made, and on August 21, a successful flight traveled 6,000 kilometers (3,700 mi) and came down on target. A few days later, the news agency TASS announced that the Soviet Union had “successfully tested a multi-stage intercontinental ballistic missile.” A second successful test flight followed on September 7. Nikita Khrushchev was hoping for a big reaction from around the world, but he didn’t get it. The missile had flown entirely over Soviet territory, and the tracking systems that today monitor North Korea’s launches did not exist. There was no proof, and it seemed the Western world wasn’t ready to believe that Russia had a working ICBM. In reality, there was still a big problem. Having risen high above the Earth’s atmosphere, the missile’s warhead had to endure extremely high temperatures created by friction as it plunged back into the air. On both test flights, the heat shield design failed completely, so instead of a dummy warhead hitting the target, burned debris fell from the sky. A real nuclear warhead would have disintegrated long before it could have been detonated.[3] It would be several months before a new design of heat shield would be ready for testing. In the meantime, parts for more R-7s were arriving, ready to be assembled and launched.

7 Korolev Was A Risk-Taker

Sergei Korolev didn’t want to wait until a new heat shield was ready to test. He knew what he wanted to do with the next rockets to be built—he wanted to launch a satellite. The Soviet military had other ideas, though. For them, getting a fully operational ICBM was the one and only priority. Launching satellites would just be wasting time on scientific nonsense; that project would have to wait. Korolev then took a huge gamble and went over the heads of the military (who were paying his wages) and appealed directly to Nikita Khrushchev. He emphasized the propaganda value of being the first country to put an object in orbit and convinced the Soviet leader to back the idea of launching a satellite with the next R-7.[4]

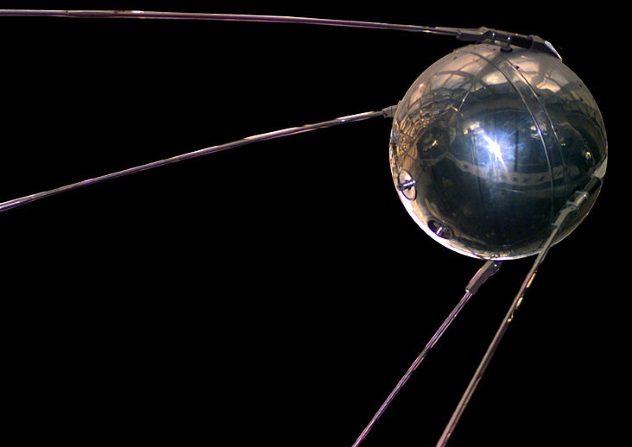

6 The Simple Satellite

Korolev knew that he had to get a satellite into orbit quickly. As soon as the redesigned heat shield was ready, the generals would insist on a return to missile testing. Unfortunately, Tikhonravov’s design, which weighed a hefty 1,400 kilograms (3,100 lb) and contained an array of different scientific instruments, was a long way from being ready. It did eventually make it into space as Sputnik III, but in the meantime, an alternative was hurriedly put together. Called PS-1, or the “Simple Satellite,” the new design consisted of a metal sphere holding three batteries and a radio transmitter, plus four antennas. All it did was transmit “bleeps” at two different radio frequencies. It was made so quickly that there were no formal drawings of the design. The technicians building it worked from sketches and verbal instructions, with the engineers more or less making things up as they went along. Korolev was acutely aware of the propaganda value of having a satellite in orbit and wanted his satellite to be as visible as possible when it circled the globe. The metal sphere was polished to a bright, shining silver. Then, to maximize visibility, reflective prisms were added to the outside of the final stage of the R-7 rocket, as it would also go into orbit.[5]

5 The Telegram That Was Lost In Translation

The launch was scheduled for October 6, 1957, but then Korolev received a telegram that seemed to say the Americans were about to send their own probe into space. Determined to be first, he brought the liftoff forward by two days. In fact, he had no need to panic. The message in the telegram had been somehow lost in translation, and there was no American launch planned—just a presentation at a conference. The mix-up resulted in October 4, 1957, becoming the day that is generally recognized as the start of the Space Age.[6]

4 The Long Wait

Today, pretty much everything in orbit around the Earth is tracked and monitored, even down to middling-sized pieces of space junk. In 1957, the Soviet Union’s tracking only extended to their eastern border on the shores of the Pacific Ocean. Korolev and his colleagues had an anxious wait of over an hour (with no doubt much pacing up and down and chewing of fingernails) before Sputnik’s signal was picked up from the west as it completed its first orbit. Only then did they know that the launch had been successful and pass the news on to the Kremlin.[7] At this point, had he been American, Korolev would have become world-famous. Instead, he remained anonymous. The Soviets referred to him as the “Chief Designer.” His real name was not revealed until his death, and the full story of the R-7 and Sputnik wasn’t known in the West until after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

3 The CIA Didn’t Mind Sputnik Flying Over The US

When Sputnik 1 began regularly passing over North America, many people in the US were horrified. They saw it, quite literally, as an invasion of their space. However, there were a few men in the CIA who were secretly (as is their way) quite pleased. They were the reconnaissance men. The intelligence agency had developed the U-2 spy plane, which made its first flight in 1955. Flying at extremely high altitude, the cameras on the aircraft could capture a wealth of valuable information. Those running the missions knew, however, that it was only a matter of time before the Russians developed a plane or missile that could reach the U-2. The next generation of spy plane, which could fly even higher and faster, would not be ready for a number of years. In the meantime, the CIA’s attention had been drawn to the idea of satellites, which seemed to be becoming a realistic proposition. The talk of Project Vanguard in 1955 set minds thinking. Would it be possible to take pictures of enemy territory from a satellite in orbit? By 1956, well before Sputnik, the first US spy satellite program, called WS-117L, had been started by the Air Force.[8] There were two problems with this idea. The first was the not inconsiderable task of building and launching a spacecraft to take the pictures and then getting those images back to Earth. The second problem was a legal one. No one was sure what rules applied when one country’s satellite passed over another nation. Did this count as an invasion of airspace? The U-2 flights were, of course, illegal, but in CIA speak, they were “plausibly deniable.” Aircraft can drift off course by accident, and if a U-2 crashed, it had no markings, and the pilot would almost certainly be killed. (This strategy blew up spectacularly in the CIA’s face when Gary Powers was captured after being shot down in 1960.) Satellites, however, could be easily tracked. There was a real possibility than an American satellite over Russia could trigger an international incident or even lead to war. Sputnik 1 neatly solved this problem. If the Americans didn’t object as it passed over the US (and they didn’t), then the Soviets couldn’t object to US satellites over Russia. Spy satellites had been given the green light.

2 The US Could Have Been First

Wernher von Braun was a man driven by a desire to build rockets, and he wanted to use those rockets to explore outer space. There are some serious question marks over the extent he was willing to ignore the moral dilemmas raised by the planned use of what he designed, but there is no doubt that he was an engineering genius when it came to developing this new technology. Von Braun spent most of World War II developing the V-2 rockets that inflicted some serious damage to London during the war. He then made a conscious decision to lead his team of engineers toward the advancing American forces and to offer their services to the US government. By 1953, von Braun was head of the US Army missile development team. He had refined and enlarged his V-2 design into the army’s first ballistic missile, the PGM-11 Redstone, which made its first flight that year. The Redstone was designed for battlefield use and had a range of just 320 kilometers (200 mi), but von Braun also visualized its use in launching satellites. In September 1954, he put forward a proposal for a “Minimum Satellite Vehicle.” This was basically a Redstone combined with three upper stages made of small solid fuel rockets. This combination, von Braun had calculated, could put a small satellite weighing 2.5 kilograms (5.5 lb) into orbit around the Earth. Von Braun requested $100,000 in additional funding to get his satellite onto space. His request was flatly rejected. Opportunity number one had been missed. The period from July 1957 to December 1958 had been designated as the International Geophysical Year (IGY), with the aim of promoting scientific cooperation between nations. In 1955, the Soviet Union announced that as part of IGY, it would launch scientific instruments into space. Entering into a spirit of rivalry rather than cooperation, US president Dwight Eisenhower then promptly declared that the US planned to put an artificial satellite into orbit as part of the IGY events. At this time, the US Army, Air Force, and Navy were all developing their own rival missile designs. Each service put forward a proposal for launching a satellite. Much to Wernher von Braun’s annoyance, the Navy won with their Vanguard rocket. As a consolation, the Army was allowed to build a modified Redstone, complete with upper stages, which was called the Jupiter-C. This was in order to test out heat shield designs for getting nuclear warheads back into the atmosphere when they reached their target. The US secretary of defense, Charlie Wilson, was not a fan of von Braun and was concerned that he might launch a satellite “by accident.” So he ordered the head of the Army missile program, General Bruce Medaris, to personally inspect the payload of each Jupiter-C before it was launched to ensure that von Braun hadn’t sneakily put a “live” satellite on top of the rocket. The first Jupiter-C launch took place on September 20, 1956. It carried a payload weighing 39 kilograms (86 lb) to an altitude of 1,094 kilometers (680 mi) and a speed of 25,750 kilometers per hour (16,000 mph). Adding one extra small stage and making the payload lighter could have boosted the speed beyond 28,485 kilometers per hour (17,700 mph) and put a satellite into orbit. The Space Age would have started more than a year before Sputnik 1. The Jupiter-C launch was the satellite that never was. Opportunity number two had been missed. As it was, the Russians launched Sputnik, resulting in huge pressure on Project Vanguard. In December 1957, what should have been a low-profile test launch became a worldwide news event. The Vanguard rocket lifted a few feet from the launch pad before exploding spectacularly. So the US government turned in desperation to von Braun’s team. They hurriedly put together a new version of the Jupiter-C including the extra stage with a small scientific payload attached. The rocket’s name was changed to Juno to try and convince the world it was not really a missile. Then, on January 31, 1958, Explorer 1 was launched into orbit, and the US was finally in the Space Race—using the Wernher von Braun plan that had been rejected in both 1954 and 1955.[9]

1 The R-7 Was A Failure As A Missile

Despite its incredible success as a satellite launcher (astronauts visiting the International Space Station today lift off on top of a stretched version of what is basically the same rocket), as an ICBM, the R-7 had numerous flaws. The complex design of a central rocket with strap-on boosters took days to assemble. Then, a minimum of seven hours were needed to fuel the rocket and get it ready for launch—hardly an instant response to an American attack. The launchpad was also aboveground; leaving it extremely vulnerable. Soviet warheads had also gotten smaller and lighter, so the huge R-7 was almost obsolete as soon as it was ready. Only a very small number were ever deployed as missiles.[10] I am an aging geek living in Birmingham, England. You can read more of my ramblings at www.thequirkypast.com