10 Florence Wolfson

For her 14th birthday on August 11, 1929, Florence Wolfson received a red leather diary. She wrote in it daily for the next five years until the little book got pushed aside in favor of other important things. In 2003, her old apartment building started to clean out their storage area. Along with a stash of steamer trunks and dressers filled with flapper dresses and sweaters, the diary was carted off to await the dumpster. There, it was saved by a building engineer, who passed it along to a writer and a lawyer. They decided to try to find the blonde girl in the photograph that was tucked in the diary’s pages. And they did find her, 90 years old when they returned the diary to her. Within the pages of her red leather diary was an extraordinary glimpse into life at the beginning of the century, when the world was progressing at a staggering rate and the Depression and World War I were casting their shadows over the world. Wolfson’s memories paint a picture of just what it was like to live in New York City at the time. Born to Russian immigrants, she grew up the daughter of a doctor and a high-class dressmaker. She talked about playing tennis and riding horses in Central Park, taking trips to the Catskills, and meeting the boy who would become her husband. But the diary also shows just how little life really changes. Although the trappings might look different, she talks about the difficulties in her parents’ marriage, her obsession with her appearance, and her desire to look like the models on the runway. She records her failures at chasing her dreams of a career in art or literature and the devastation she feels. She talks about her desire for love, her boyfriends and her girlfriends, and her wish to be complete. It’s a priceless glimpse into an ordinary life that shows that no matter how much our world changes, the human soul remains largely the same.

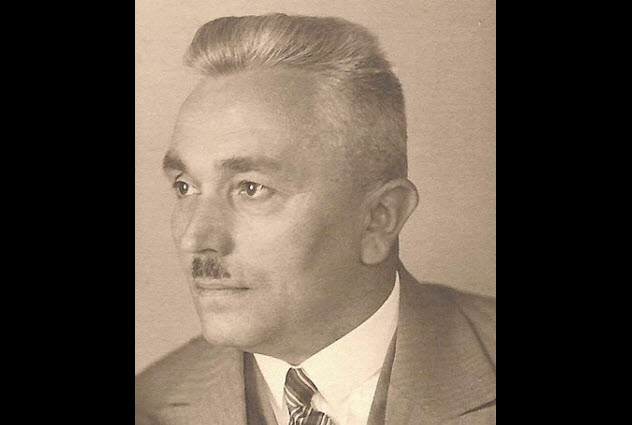

9 Friedrich Kellner

At the end of World War II, many Germans denied that everyday citizens had known the full extent of the Nazis’ plans. But one man’s diary brought that claim crashing down. Born in 1885 to humble beginnings, Friedrich Kellner grew up to marry an office clerk and serve in World War I. When he later read Mein Kampf, he realized to his horror that Hitler was serious. On September 26, 1938, Kellner began writing in his Laubach apartment about the rise of the Nazi Party from the view of an ordinary citizen. He wrote, “I fear that few decent people will remain after events have taken their course, and that the guilty will have no interest in seeing their disgrace documented in writing.” His predictions were eerily accurate. As a German citizen who didn’t join the Nazi Party, he wanted to make sure that everyone was held accountable for what they knew and did. He saved newspaper articles, speeches that were published, propaganda pieces, military news, and obituaries. He recorded his feelings about what was going on in his country. Most importantly, he wrote about the events that people would later claim hadn’t been public knowledge, including crimes against Jewish people and those in mental hospitals, which had been set up to kill people deemed unworthy of life. He revealed the mind-set of many ordinary citizens who believed that they needed to win the war, not because they agreed with Hitler’s actions but because of what would happen to them if they lost. For years, Kellner hid the 10-volume, 1,000-page diary in a secret compartment in his dining room cabinet. He hadn’t been able to safely fight the Nazis in the present. So he preserved his writings as a secret weapon that could be made public someday to prevent such evil from happening again. When his American grandson, Scott, whom he had never met, sought him out in Germany in 1960, Kellner finally found someone to trust with the truth. Despite a crusade by his grandson to get the diary published, it was almost lost. After countless rejections, the original volumes were put on display at Texas A&M’s George Bush Presidential Library, where they finally attracted worldwide attention from newspapers and magazines. Plans were made to publish a biography of Kellner, film a documentary, and publish the diary as a book in Germany.

8 The First Fleet Journals

The First Fleet was the name of a group of ships that took more than 1,500 settlers from England to their new home in New South Wales. The first ships left England on May 13, 1787, carrying a motley mix of military officers, families, and convicts. Heading first down the coast of Africa before crossing the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro, they then headed back to the Cape of Good Hope before going onward to Australia. The State Library of New South Wales has a series of diaries and journals written by some of those voyagers, recording the daily events of the journey and their first impressions of their new home. Some, like Arthur Bowes Smith and William Bradley, sketched drawings of kangaroos and plants, new sights that were unlike anything the average European citizen had ever seen. Jacob Nagle joined the fleet as a regular sailor. Born in Pennsylvania, he had fought in the American Revolution and been taken prisoner by the British. After that, he opted to swear allegiance to the Royal Navy and was dispatched on the First Fleet. His journal details his exploration of Botany Bay, the crew’s stranding on a reef near Sydney Cove, and the day-to-day life of a low-ranking sailor. Other diaries, like that of Lady Penrhyn’s surgeon Bowes Smith, detail the names and crimes of the convicts on board and provide a more personal look into the lives of the passengers and crew. He also documents their first encounters with the natives and draws the first sketch of an emu by a European.

7 Nasir Khusraw

In 1046, Nasir Khusraw was working as an administrative clerk in what is now Tajikistan when he quit his job and set off on a “quest for truth.” Although no one’s quite sure what truth he was seeking, his chronicles of the journey have provided an incredible look into the 11th century. Khusraw’s travels lasted seven years. His diaries record the many languages he heard in the city of Akhlat, noting that even the most small-town people there could speak three languages fluently. He talks about the people who lived in Tripoli, always afraid that they were going to be attacked by a Byzantine army. Khusraw notes that with churches, mosques, and synagogues often located in the same area within a city, many of the people who crossed paths on their way to worship had mutual respect for each other while still believing and praying in their own way. In Hamath, Syria, he says that he believes the river was called Asi (meaning “rebellious”) because it also ran through Byzantium, going between the lands of the faithful and the lands of the infidels. Published as Safarnama, the record of his travels looks at the relationships between people and their religions, their cities, and their surroundings on an extremely personal level.

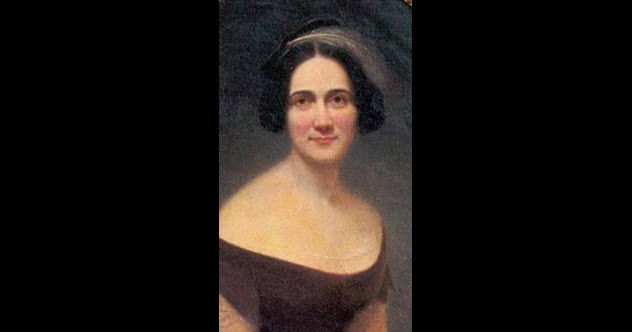

6 Mary Chesnut

Mary Chesnut had the good fortune to be born into a life of privilege. The daughter of a governor and member of the House of Representatives, she married a lawyer eight years her senior in 1840. In February 1861, she began documenting everyday life during the Civil War in her diary. When she died childless in 1886, her best friend inherited her diary and published it in 1905 as A Diary from Dixie. Today, it remains one of the best sources of information on everyday life in the Carolinas during the Civil War. Even though Mary was well educated and spoke several languages, her diary has been lauded for its complete lack of political motivations and literary voice, recounting events simply as she saw them. Although most of us envision a senator’s wife living a life of privilege, that wasn’t the case in the mid-1800s. These political wives knitted socks for soldiers while going without shoes themselves, raised families at a time when money was tight or nonexistent, and moved so frequently that they had no real home. Mary’s diaries keep the war from becoming impersonal. On one page, she recounts the thrill of receiving a basket of cherries and then the paralyzing terror that came with a stack of telegrams bearing the names of the dead. On another page, she tells of newspapers condemning women who wear all their finery as they parade past the wives of soldiers away at the front. According to the diary, Mary sold her dresses. She also struggles to understand why a female slave, who had been a nursemaid to a young family, refused to leave Columbia with Mary’s family. She recounts weddings and funerals, including how someone’s death impacted those who had loved them the most, something often overlooked on the losing side of war.

5 Herman Kruk

In the earliest days of World War II, refugees fled Warsaw and settled into a precarious existence in Vilna. One-time librarian Herman Kruk was among those refugees, and he kept a diary documenting everything that went on in the Vilna Ghetto. In 2003, his 800-page diary was published as The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania: Chronicles from the Vilna Ghetto and the Camps, 1939–1944. In the diary, Kruk described his fears and feelings as well as stories of his friends, family, and neighbors. He also included whispered, half-believed tales of what the Nazis were truly doing in the killing fields in Ponar and during the uprisings in the ghettos. Kruk founded a library while living in the ghetto, and he shares his thoughts on sorting through looted books under the direction of the Nazi overseers, wondering if he’s saving the books or choosing them for destruction. Even as war raged, Kruk persuaded the ghetto’s council to buy Jewish texts and letters. He also set aside books for prisoners laboring in camps. He documented the power struggles within the ghettos, the fight to maintain a school system for the children who lived there, and his disgust with some of his fellow Jews for their political views and unwillingness to uphold their morals. Without the benefit of hindsight, he captures life in the ghettos in the moment and is eventually deported for his ideas. Around 20,000 Jews lived in the Vilna ghettos. They tried to keep their traditions, even building theaters, attending poetry and dance recitals, and holding concerts. By January 1942, most of those exiled to Vilna had been killed. In March 1942, Kruk wrote, “Life is stronger than anything.” In September 1943, he was sent to an Estonian concentration camp. One year later, he wrote his last diary entry and buried it in front of six witnesses. The next day, Kruk and the remaining Jews were executed. The following day, the Soviet Army liberated the camp, and his diary was retrieved by one of the surviving witnesses.

4 Robert Shields

Robert Shields was a former English teacher and minister. When he passed away in 2007, he left behind one of the largest, longest, and most complete diaries ever. Beginning in 1972, he was struck by the need to document absolutely everything that happened in his life—from the noteworthy events to more details about his urination habits and bowel movements than anyone should record. He slept in two-hour increments so that he could record his dreams and spent around four hours every day typing up his daily report in his underwear. Shields finished his diary in 1996 and gifted the whole lot to Washington State University in 2000. Housed in 81 cardboard boxes, it even includes things like receipts and samples of his nose hairs, just in case anyone ever decides they want to do DNA testing on the diary’s author. Each page is bizarre in its completeness. Text is broken up into blocks of time that quite literally include every minute of every day, filled with things like turning on the stereo (and the music he listened to), watching television shows (and summarizing what the episode was about), lipreading psalms, and listening to the radio (including the songs played and the contributions of on-air callers). He also recorded the exact amounts of everything he ate, where it came from, and who bought it. Occasionally, he included receipts for the food. There’s also an extraordinary amount of space devoted to discussing the details of his bathroom habits, from reading material to color and consistency.

3 George Fletcher Moore

Born in Ireland and educated at Trinity College, George Fletcher Moore was originally denied a legal position in the new Australian Swan River settlement. In 1832, he decided to head to the new colony regardless of his position there. So he bought some sheep and leased a farm outside of York. In his diaries, Moore documented his role in the blossoming colony, providing an unprecedented look at what life was like for settlers in Australia. He wrote about his agricultural exploits and the conflicts between settlers and the Aborigines. Unlike many of his European colleagues, Moore grew fond of his Aboriginal neighbors. He learned their language, their stories, and their customs. But he wasn’t immune to the conflict between the two peoples, lamenting that they stole his pigs. Quickly named the secretary for the Agricultural and Horticultural Society, Moore describes balls and celebrations along with his discovery of new grazing lands, his expeditions to chart new rivers, and his family’s personal difficulties. He tells stories of ships dispatched to look for others rumored to have wrecked in Sharks Bay, of meeting impossibly tall natives, of having to eat kangaroo meat and the danger in killing the animals to get it, of translating the Lord’s Prayer into the Aboriginal language, and of teaching missionaries how to communicate with the native people. He also recorded hundreds of Aboriginal words, their pronunciations, their meanings, and the gestures that were sometimes used with them. He included the words for different species of animals and plants, transforming his diary into an important cultural document.

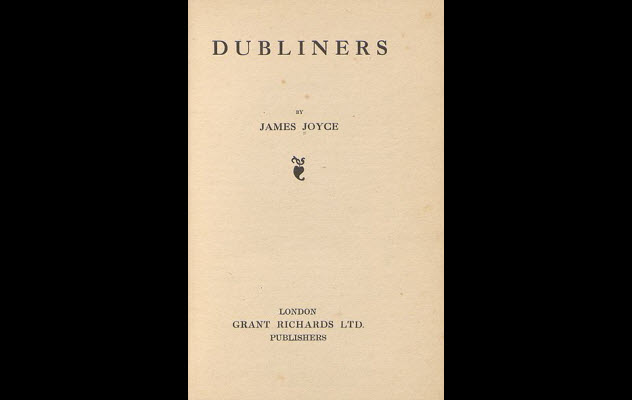

2 Stanislaus Joyce

Preferring that his friends and family call him “Stannie,” John Stanislaus Joyce was the younger brother of literary giant James Joyce. Although Stanislaus was employed as an office clerk, his diaries have provided an unprecedented, behind-the-scenes look at the life of one of literature’s most bizarre figures. Stanislaus began keeping his diary when he was 18. James regularly read the diary and used his brother for a steady stream of ideas. As James moved from Ireland to Paris and Rome, Stanislaus remained in Dublin and kept James apprised of the latest news. Stanislaus also supported James financially, which his diaries show he resented. He became even more bitter when James broke his promises to dedicate Dubliners to Stanislaus and write a character based on him for A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. When it came time for an official biography to be written about James, Stanislaus’s diary was used as one of the key sources. It’s a strange glimpse into a rather tormented family, and Stanislaus tells the unvarnished truth. He talks about their outright hatred of Catholicism in particular and religion in general, painting a picture of his brother as a deliberate sinner who distanced himself from the church. The two men engaged in a constant battle to reconcile their feelings about religion with their deeply religious mother.

1 Alexander Berkman

At the turn of the 20th century, Russian immigrant Alexander Berkman committed what he claimed was the first act of terrorism on American soil with his attempted murder of steel plant manager Henry Frick. Reporting directly to Andrew Carnegie, Frick became embroiled in a strike that involved 3,000 angry workers, state militia, and the Pinkertons. Frick survived the attempt on his life, and Berkman served 14 years in jail. However, the source of Berkman’s motivation began years earlier. Born in 1870 to a merchant family in Russia, he was first exposed to murder as a method of change when a bomb exploded outside his school after Tsar Alexander II was assassinated. These events shaped Berkman’s idea of assassination as a viable means of changing the world, a belief that stayed with him even after he emigrated to the US at age 18. In the US, he edited some anarchist journals, helped to organize unemployed workers in New York, and served prison time for his involvement with strikes. In December 1919, he was deported to Russia during the Red Scare in America. Berkman began his diary with this event. He kept the diary between 1920 and 1922, writing about the Russian Revolution and its effect on ordinary citizens. He tells of his return to his homeland and his welcome as one of the revolutionaries fighting for the common person. The revolutionaries asked him to speak as someone who had just returned from America, to tell them that the same injustices were occurring overseas, and to reassure them that the starving masses were on the edge of a revolution that would change their world. As recorded in his entries, he sees the struggles in every landmark and describes the graves of those who died while fighting for the rights of the worker. But Berkman became disenchanted with the ruthless Bolsheviks and decided to leave Russia in December 1921. That’s when his diary ends. It was later published as The Bolshevik Myth. Read More: Twitter