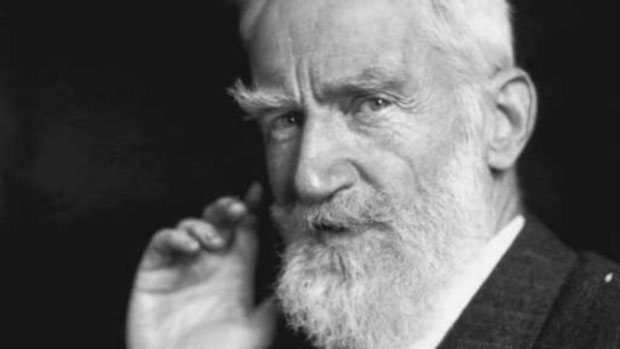

10George Bernard Shaw On Shakespeare

George Bernard Shaw, the only writer to receive both an Academy Award and the Nobel Prize for Literature, produced a variety of well-known (and award-winning) plays, the most famous of which was Pygmalion. Apparently, his success as a playwright led him to believe he had the credentials to make a few scathing comments about Shakespeare himself: “With the single exception of Homer, there is no eminent writer, not even Sir Walter Scott, whom I can despise so entirely as I despise Shakespeare. The intensity of my impatience with him occasionally reaches such a pitch, that it would positively be a relief to me to dig him up and throw stones at him.” Shaw wasn’t the only famous author who loved hating the Bard: Voltaire called Shakespeare a “drunken savage” who only appealed to audiences in “London and Canada.” For good measure, he also described his works as a “vast dunghill.”

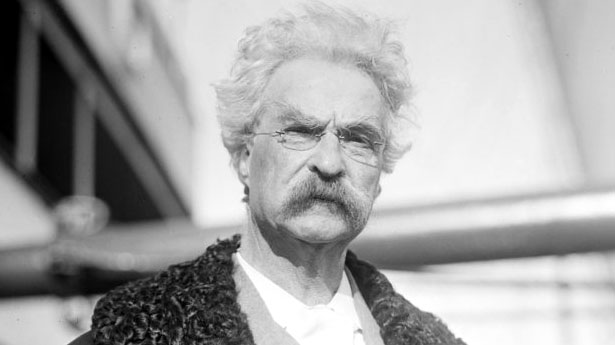

9Mark Twain On Jane Austen

For many, Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain) remains the quintessential American author. And apparently he harbored some strong feelings about perhaps the quintessential English novelist. In a critical essay on Jane Austen’s works, Twain remarked: “She makes me detest all her people, without reserve. Is that her intention? It is not believable. Then is it her purpose to make the reader detest her people up to the middle of the book and like them in the rest of the chapters? That could be. That would be high art. It would be worth while, too. Some day I will examine the other end of her books and see.” “Every time I read Pride and Prejudice, I want to dig her up and beat her over the skull with her own shin-bone.” Twain’s talent for vitriol wasn’t limited to Austen—he also penned a hilarious essay titled “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses,” in which he claimed that Cooper’s The Deerslayer managed to commit “114 offenses against literary art out of a possible 115 . . . its humor is pathetic; its pathos is funny; its conversations are—oh! indescribable; its love-scenes odious; its English a crime against the language.” Some argue that Twain addressed these jibes at other famous authors just for the fun of it.

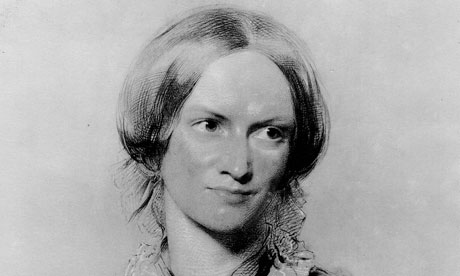

8Charlotte Bronte On Jane Austen

Jane Austen might be known for her refined characters, but she certainly had a way of making people angry. Charlotte Bronte, a near-contemporary of Austen known to prefer passion over stolid practicalism, let loose after a cursory reading of Pride and Prejudice: “She ruffles her reader by nothing vehement, disturbs him with nothing profound. The passions are perfectly unknown to her. What sees keenly, speaks aptly, moves flexibly, it suits her to study: but what throbs fast and full, though hidden, what the blood rushes through, what is the unseen seat of life and the sentient target of death—this Miss Austen ignores.” Later, in a letter to a friend who had warned her not to be too melodramatic, Bronte said she couldn’t have tolerated being confined to the refined gardens and elegant society featured in Austen’s novels. Authors and critics often base their opinion of Austen on her development of emotion (or lack thereof). Ian Watt claimed that Austen’s works appeal only to those who view logic as superior to emotion. Virginia Woolf, on the other hand, valued Austen’s work, arguing that she was “mistress of greater emotion than appears on the surface.”

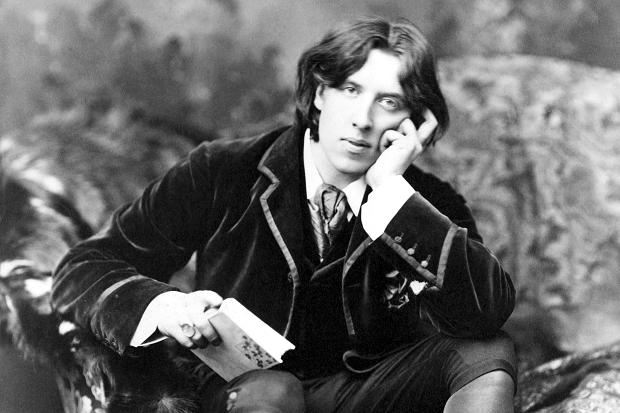

7Oscar Wilde On Alexander Pope

Both authors are among the most prominent in British history, among the few to be honored with memorials in Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey. But it appears that Wilde wasn’t a fan of his renowned predecessor. A famously quotable author, full of flippant jabs and insults, Wilde once wrote a letter to a friend in which he observed: “There are several ways to dislike poetry; one is to dislike it, the other is to read Alexander Pope.” Since Pope was dead at the time, he didn’t get the chance to reply to Wilde’s putdown, but it’s a fairly safe bet that his response would have been scathing. After all, when the writer Lewis Theobald criticized his adaptations of Shakespeare, Pope responded by making him the main character of an epic, four-volume work of poetry called “The Dunciad,” in which he is supposedly the son and favorite of the goddess “Dulness.” When he later fell out with the playwright Colley Cibber, Pope rewrote the poem to make him the title character instead. Despite his seeming disdain, critics have noted allusions to Pope’s work in Wilde’s only novel, The Picture Of Dorian Gray, where a turn of conversation strikingly resembles a line from Pope’s The Rape of the Lock.

6Virginia Woolf On James Joyce

In a 1922 letter to T.S. Eliot, Woolf asked the poet for his sincere opinion on Joyce’s newly released book, Ulysses. That same year, she wrote to her sister, encouraging her to get to know Joyce: “I particularly want to know what he’s like.” However, Woolf’s fascination with Joyce didn’t at all indicate that she respected his literary skills. After reading the first few hundred pages of Ulysses, she confided to her diary: “An illiterate, underbred book it seems to me: the book of a self-taught working man, and we all know how distressing they are, how egotistic, insistent, raw, striking, and ultimately nauseating.” Woolf wasn’t the only author who had trouble making it through Ulysses. D.H. Lawrence, often associated with Joyce as a master of the modern novel, claimed to be “one of the people who can’t read Ulysses,” although he conceded that Joyce would doubtless “look as much askance on me as I on him.”

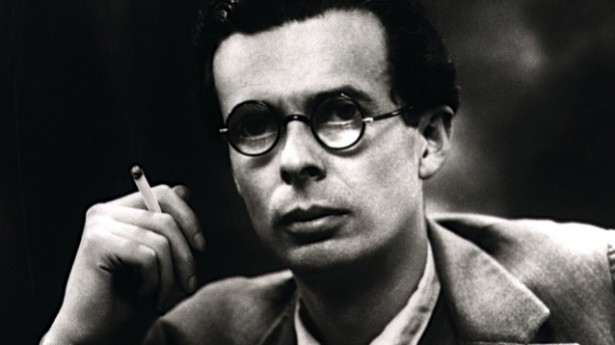

5T.S. Eliot On Aldous Huxley

Some experts seem to think that T.S. Eliot and Aldous Huxley admired each other, at least to some degree. Both were members of the Bloomsbury Circle of Lady Ottoline Morrel, an artsy social group of the time, and both read the others’ work closely. Huxley’s most famous work, Brave New World, and Eliot’s The Hollow Men share many of the same ideas. But that didn’t stop Eliot from taking potshots at Huxley, once remarking: “Huxley, who is perhaps one of those people who have to perpetrate thirty bad novels before producing a good one, has a certain natural—but little developed—aptitude for seriousness. Unfortunately, this aptitude is hampered by a talent for the rapid assimilation of all that isn’t essential.” H.G. Wells, another author whose works centered on futuristic, often dystopian scenarios, was greatly disappointed in Huxley’s dark vision of things to come, saying that a writer of Huxley’s standing had “no right to betray the future as he did in that book.”

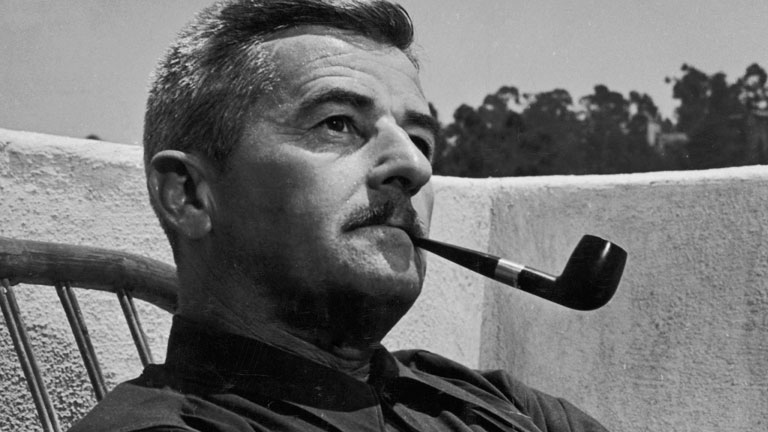

4William Faulkner On Ernest Hemingway

Some authors, like Huxley and Wells, fall out over philosophical differences. Faulkner’s beef with Hemingway was much more straightforward— he didn’t like his style. Of Hemingway’s characteristically brief, simple sentences, Faulkner said: “He has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary.” Faulkner’s writing style was certainly more complex than Hemingway’s—it’s not unusual to encounter page-long sentences in his works. Those prolix sentences weren’t an accident; they were part of his writing philosophy. In an interview, Faulkner said he wanted “to put the whole history of the human heart on the head of a pin . . . the long sentence is an attempt to get [a character’s] past and possibly his future into the instant in which he does something.” And forget using a dictionary to look up words—some of Faulkner’s fabricated portmanteau words, including “allknowledgeable,” “droopeared,” and “fecundmellow,” wouldn’t be found in even the most exhaustive reference works.

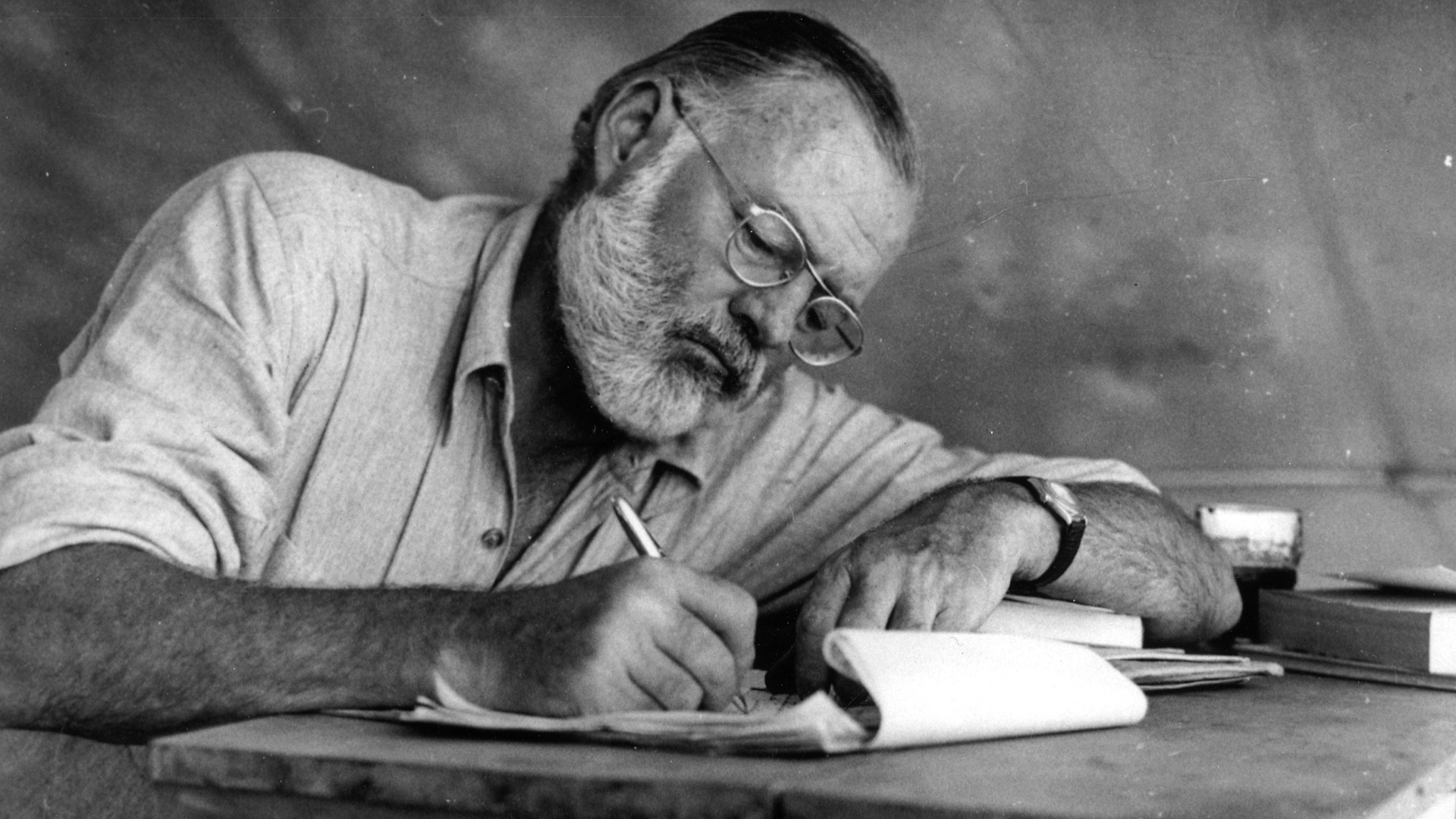

3Ernest Hemingway On William Faulkner

Of course, as a man who once responded to an insult by punching Orson Welles, Hemingway wasn’t about to back down from a fight. In response to Faulkner’s “dictionary” quip, Hemingway sneered: “Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words?” Hemingway believed that writing should be clear and straightforward enough that readers wouldn’t have to hunt down a reference book to decipher an idea. The best writers don’t need to consult dictionaries, he maintained. Ironically, some of Hemingway’s works are riddled with foreign words and phrases, which can be tricky for a monolingual English-speaker to understand. Apparently, sending readers to a dictionary was only a problem for Hemingway when an English dictionary was required. If you want to copy Hemingway’s style, the ever-helpful Hemingway App can assist you by highlighting sentences that need to be simplified and adverbs that need to be deleted. If, on the other hand, you prefer to adopt Faulkner’s style, you might want to sit down with an unabridged Oxford English Dictionary and start reading and randomly combining words.

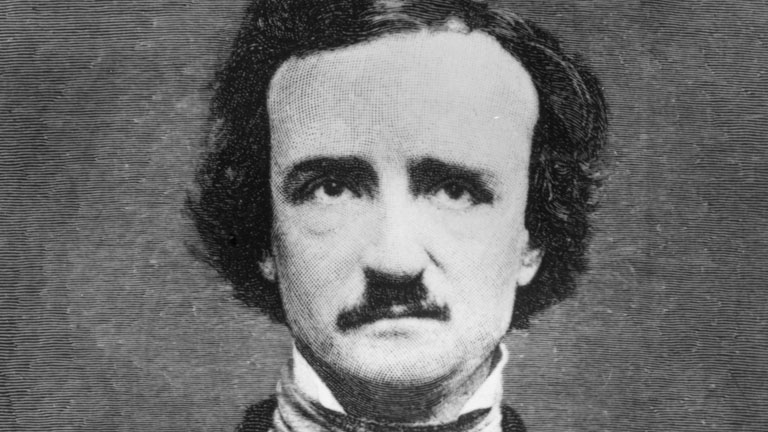

2W.H. Auden and T.S. Eliot On Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe was one of the great writers of the 19th century. Many call him the inventor of the murder mystery, and he was certainly a dark, brooding predecessor to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie. Poe also won worldwide acclaim (mostly posthumously) for his lyric poetry, which often focuses on death or loss. But not everyone approved of Poe’s macabre tales and melodramatic, depressed style. The poet W.H. Auden was less than complimentary, calling Poe: “An unmanly sort of man whose love-life seems to have been largely confined to crying in laps and playing mouse.” T.S. Eliot, slightly more politely, attributed to Poe: “the intellect of a highly gifted person before puberty.” Poe’s life was almost as rocky as his dark stories and poems. After dropping out of school because of financial trouble, finding out his sweetheart had become engaged to another man, and going to visit his mother only to find that she had died, he set out on a quest for fame. When he was 27, he married 13-year-old Virginia Clemm, who died of tuberculosis a short time later. Poe ultimately expired in a manner as mysterious as his own macabre stories—he was found dead in a public house after disappearing in Baltimore for five days. Today, Poe is either hailed as a literary mastermind or reviled as a pedophile with a fetish for blackbirds.

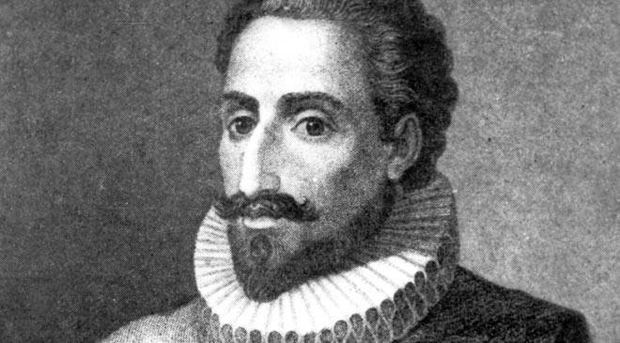

1Martin Amis On Miguel de Cervantes

We all have them—those family members or friends whose visits only serve to convince us that they’ve completely lost their minds. Martin Amis, an English novelist most famous for the cult classics Money and London Fields, seems to think Miguel de Cervantes’s famous 17th-century masterpiece embodies that eccentric, ever-inappropriate relative: “Reading Don Quixote can be compared to an indefinite visit from your most impossible senior relative, with all his pranks, dirty habits, unstoppable reminiscences, and terrible cronies.” Though Don Quixote met with a mixed reception on its release, many now hail it as the first real modern novel. Harold Bloom, well-respected literary critic and Sterling Professor of Humanities at Yale, only has scintillating things to say about Cervantes’ landmark novel: “Cervantes and Shakespeare, who died almost simultaneously, are the central western authors, at least since Dante, and no writer since has matched them, not Tolstoy or Goethe, Dickens, Proust, Joyce.” In the same article, Bloom makes an interesting point: “Cervantes inhabits his great book so pervasively that we need to see that it has three unique personalities: the knight, Sancho, and Cervantes.” If that’s true, maybe Cervantes himself is the personification of that “impossible senior relative” we all know. Steffani is a freelance writer and coffee addict living on the island of Guam. She’s also a scuba diver, a knitter, and an E.A. Poe aficionado who often gets segments of “The Raven” stuck in her head on repeat. Steffani blogs about life in Guam at OriginalFootprints.com.