Surprisingly, these multi-million-dollar works of art, many of which are not by painters whose names are well known to the public, are apt to leave many wondering who in their right minds would pay anything, much less millions, for such pieces of—well, art. Of course, art is subjective, and people’s tastes sometimes differ widely. Still, most of us won’t be able to resist scratching our heads, pondering how these paintings ever commanded even a fraction of their sale prices. Judge for yourself: are any of these multi-million-dollar paintings worth the money collectors paid for the dubious privilege of owning them?

10 Untitled by Robert Ryman

Depending on a person’s frame of reference, a few of the paintings of American minimalist painter Robert Ryman (1930-2019) looks like either a bit of stucco plastered onto a rectangular surface or a square-shaped toaster pastry covered in white icing and spotted with green mold. Apparently, Ryman liked the painting so well that he recreated it numerous times, substituting different colors to create the “moldy” effect he developed in 1953 as a beginning artist using oil on canvas board to experiment with technique. As Suzanne Hudson points out, Ryman became “known for producing scores of white squares,” even though not all his squares are white since he also used colors on occasion. There was a reason for this repetition of (mainly) white squares. Ryman was not concerned with creating representational work. “He was not interested in composing a picture,” Hudson explains, “but in clarifying process.” He wanted to learn how paint worked. He also wanted to reduce the physical space between a painting and the wall on which it hung. To this end, in one experiment with technique, the minimalist painted his work directly onto the wall. Although he was an innovative painter and a conceptual artist, Ryman’s work always seemed to return to his initial experiment with painted squares, white or otherwise.[1] Some might look askew at the artist’s fixation. Still, there is no denying that his “white squares” are worth a lot of money for some collectors, one of whom paid $15 million for one of the equal-sided rectangles, and it didn’t even have a title—unless Untitled counts as one.

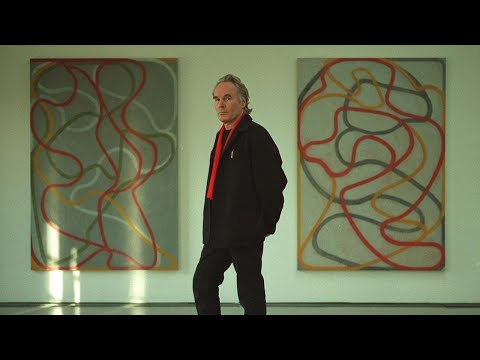

9 Point by Brice Marden

American artist Brice Marden (1938- ), another minimalist, also produced a series of square paintings, seeming, for a time, as fixated as Ryman had been obsessed with his own scores of white squares. As Roberta Smith points out in her review of Marden’s work, “Throughout the 1970’s Marden stuck to his one-canvas/one-color formula with monkish devotion.” However, unlike those of Ryman’s squares, the sides of Marden’s rectangles are not equal in length. The top and the bottom sides are typically twice the length of the right and left sides. The rectangle itself may be divided into thirds, each of which may be either a different color, as in For Pearl (1970), or different shades of a single color, as in Point (1969). It is especially impressive that one of Marden’s earlier transitional works, Point, sold at auction for over $6 million![2]

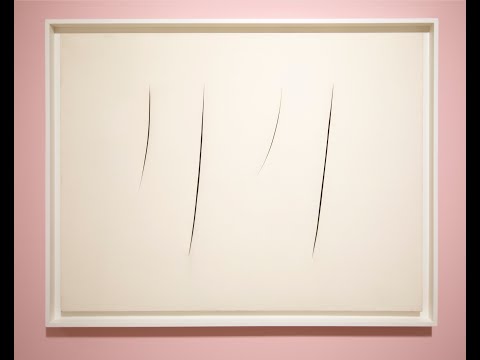

8 Concerro Spazale, Atteste by Lucio Fontana

Twelve juxtaposed diagonal lines at varying heights and lengths, some thin and light, others slightly thicker and darker, looking more like slashes than calculated strokes of a brush, make up the entirety of Argentine-Italian Lucio Fontana’s Concerro Spizale (Spatial Concept), one in a series of similar monochrome canvases. The succession of paintings, the artist said, constitutes “an art for the Space Age.” And it does look a little like the type of painting that George and Jane Jetson might have on a wall of their Las Vegas Stratosphere-like house or Mr. Spock would frame on a wall of his starship Enterprise living quarters. The idea for his Space Age art resulted from an accident of sorts. According to a biographical sketch of the painter, in 1948, during “a rage, Lucio Fontana (1899-1968) destroyed a painting by piercing his canvas. From this act of destruction, a new concept of art was formed” by which he achieved a three-dimensional effect not by the traditional trompe d’oeil technique, but by puncturing and tearing the surface of the canvas to attract attention to the space behind and before it. His Concerro Spizale is divided into two types: Bucchi, in which holes in the canvas produce the effects, and Tagli, in which knife slashes accomplish the same purpose.[3] The founder of Spatialism’s innovative style commands high prices. In a Sotheby’s auction, one of the paintings in his Concerro Spizale series sold for a whopping $12.78 million!

7 Black Fire I (1961) by Barnett Newman

Early in his career, American artist Barnett Newman (1905-1970) experimented with surrealism, during which period he used “zips,” or thin vertical lines, to divide his paintings’ colored areas. Newman’s statement about the religious inspiration for his work may explain the titles of some of his early works such as Adam and Eve, Uriel, and Abraham and of his series Stations of the Cross. “What is the explanation of the seemingly insane drive of man to be painter and poet,” Newman asks, “if it is not an act of defiance against man’s fall and an assertion that he return to the Garden of Eden? For the artists are the first men.” The artist was also interested in creating works that did not rely on the representation of human forms or landscapes. He wanted, instead, to eschew “the European tradition of formal pictorial arrangement.” His solution was to avoid presenting a dominant “figure” on a recessive background. To this end, the canvas on which Black Fire I (1961) is painted is divided in half. The left side is black; the right side, light beige. Just left of center, a thin vertical black line further separates the beige side of the painting so that it appears that both the black and the beige extend into one another’s territory, struggling to possess the entire canvas.[4] In May 2014, Black Fire I sold to a private owner at a packed Christie’s auction for $84.2 million, over $30 million more than the auction house had predicted!

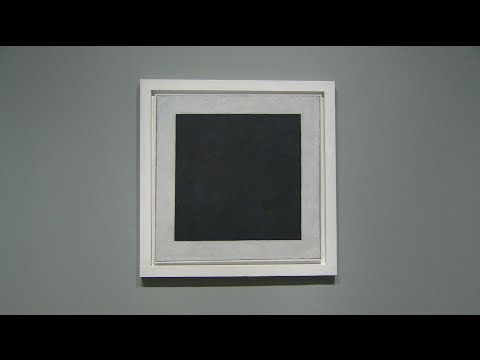

6 Suprematist Composition (1916) by Kazimir Malevich

Suprematist Composition by Soviet avant-garde artist Kasimir Malevich (1879-1935) attracts the eye by its design, which features vibrant colors and a diagonal composition in which rectangular forms seem to float, suspended midair. One of a series called Suprematist Composition, his 1916 painting of the same title, like much of the artist’s other work, shows a fascination with geometric shapes and precision which “encouraged his followers to examine Supremacist perspectives for themselves,” writes John Milner in Kazimir Malevich and the Art of Geometry. One of Malevich’s followers, in fact, confined himself to the use of a compass and a ruler as the means by which to compose drawings and paintings. Despite his own fascination with geometry, Malevich himself preferred to “let [his forms] fly.”[5] His followers were not the only ones intrigued by Malevich’s innovative approach to painting. Suprematist Composition (1916) sold at a Sotheby’s auction for $85.8 million!

5 Untitled by Jean-Michel Basquiat

One of American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat’s untitled works features a misshapen black skull (with facial features outlined in white, no less) afloat in a blue sky beside white shapes vaguely resembling buildings. The painting looks much like a graffito that a passerby might see on a street in almost any city in the world. It even bears a “tag,” or graffiti artist’s signature, the letters “AG,” in the lower-left corner of the canvas. Watch this video on YouTube What the painting is intended to suggest is difficult to say. The images seen through the skull’s forehead, inside its mouth, and through what appears to be a window in one of the vague building-like shapes might offer clues, but they are themselves merely shapes rather than representations of objects or human subjects. As such, they are difficult to interpret, which may be the artist’s intention. It seems no accident, though, that the painting resembles a graffito; Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) was a New York City graffiti artist, and his painting was not executed with oils but with spray paint. Although the skull might not be to everyone’s taste, Basquiat’s world-famous painting commands respect among collectors—it sold for over $110.5 million in 2017![6]

4 Flag (1954–1955) by Jasper Johns

Flag is an apt title for the painting of the 48-star American flag by American abstract expressionist Jasper Johns (1930- ). The work was inspired by a dream that the painter, a recently discharged soldier, had the night before he began to paint it. The work, writes Carolyn Lanchner, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, is often compared to Belgian surrealist Rene Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe). Watch this video on YouTube However, the relationship between Johns’s painting and Magritte’s is antithetical: whereas the surrealist’s painting points to the boundary between reality and illusion…Johns’ painting “collapses their difference.” Flag sent a still-memorable jolt to the art world.[7] In 2010, over half a century after Johns created the work, Flag delivered another “memorable jolt” when it sold at a private sale for an “estimated” $100 million!

3 Masterpiece by Roy Lichtenstein

American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein’s Masterpiece (1962) simulates a comic book panel showing a blonde woman alongside the dark-haired man who created the painting they are admiring. Their white complexions result from the Ben-Day dots common to the medium. The painting of the comic book panel includes a dialogue balloon indicating that the female character is speaking. “Why, Brad darling, this painting is a masterpiece! My, soon you’ll have all of New York clamoring for your work!” According to the Art Institute of Chicago, in creating his painting, Lichtenstein adapted an actual comic book panel, altering both the image and the text and changing the setting from the interior of the automobile in which the couple drove while “having an uncomfortable conversation” to an art gallery in which the woman compliments the artist. In the comic book panel, she says, “But someday this bitterness will pass.” The change in the dialogue, the Art Institute of Chicago’s commentary on Lichtenstein’s painting notes, “is a nod to Lichtenstein’s sense of humor about his newfound fame in the art world.”[8] The sale price of Masterpiece must have put a grin on the artist’s face: Agnes Gund, president emerita of the Museum of Modern Art, sold the painting for an impressive $165 million!

2 No. 6 (Violet, Green and Red) (1951) by Mark Rothko

In 1951, American abstract painter Mark Rothko (1903-1970) painted No. 6 (Violet, Green and Red), which shows horizontal bands of violet, green, and red—or red-orange, actually. There is much more to the painting than meets the eye. According to a gloss on the work, which sold for $184 million, it is one of 36 pieces in the “Bouvier Affair”—an ongoing court battle between Russian tycoon Dmitry Rybolovlev and his art dealer, Yves Bouvier. Watch this video on YouTube More specifically, the Bouvier Affair is a complex series of lawsuits, international in scope, involving allegations that Bouvier defrauded Rybolovlev out of millions of dollars by using inflated prices or false documents to manipulate “prices in the sale of art works” by not only Rothko but also by Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, Paul Gauguin, Edgar Degas, and Leonardo da Vinci. The result, allegedly, was that the paintings were sold for much more than their actual market value.[9]

1 Interchange (1955) by William de Kooning

American abstract expressionist William de Kooning tops our list, his 1955 Interchange having sold for more money than any other painting purchased prior to September 2015. The seller was the David Geffen Foundation and the buyer, American hedge fund manager Kenneth G. Griffin. Today, its sale price remains second only to Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, which sold for $450.3 million in November 2017. The work of art certainly makes many scratch their heads in wonder. Sure, it’s abstract, resembling a jumbled, somewhat ill-defined patchwork of colors and shapes that, more than anything, tend to confuse the viewer. It’s not a stretch to suggest that the mishmash might even make a body dizzy. What, exactly, is Interchange? Fortunately, Bart Barnes’s article in a 1997 issue of The New York Times offers a take on de Kooning’s mess. “His paintings shifted between representation and abstraction,” Barnes hints. Then, if we’re still not quite sure what we’re looking at, he comes right out and tells us: The “fleshy pink mass at its center [represents] a seated woman.”[10] With this mystery solved, we can move on to another. How much did Griffin pay for the privilege of owning Interchange? (Drum roll, please.) The painting set him back an astonishing $300 million!