However, not all religiously significant objects fit this pattern. Some, in fact, are quite small and seemingly mundane to the average onlooker. Only someone who truly knows the back stories behind the objects could get excited about things like… See Also: 10 Gruesome Acts Of Self-Torture That Will Horrify You

10Beard Clippings

Readers with facial hair will be familiar with the routine of cleaning up after a trim or shave: wiping up the seemingly endless little bits that get all over the bathroom counter. And anyone who’s been in a barbershop or hair salon knows how severed hair gets treated in those establishments, being unceremoniously swept up and dumped in the garbage. Most everyone, then, would conclude that stray beard clippings would be nothing to arouse enthusiasm. . . unless they belonged to a 6th century man revered by one quarter of the world’s population. The wearing of beards is a popular practice among Muslim men. They are used to emulate the reported appearance of Muhammad, whom Muslims recognize as the founder and principal prophet of the Islamic faith. But even long beards need a trim every now and then; one of Muhammad’s companions, Salman the Persian, is credited with serving as the Prophet’s barber whenever the occasion called for it. Tradition holds that the hairs resulting from one such trim were kept by onlookers. Some hairs were parceled out individually, while at least one was later placed into a glass reliquary. The early history of the Holy Beard does not seem to be well-documented, but by the 1500s a fitting destination had been established: the Chamber of Holy Relics in Istanbul. Located within the Ottoman sultan’s Topkapi Palace, this chamber would spend the next few centuries filling up with various treasures, including Muhammad’s footprints, mantle, broken tooth, and personal weapons. These were reverently stored alongside relics associated with several Old Testament patriarchs, including Abraham, Joseph, Moses, and King David. As the foremost leaders of Muslim political and religious life, the Ottoman sultans received all of these relics over time as their original locations were threatened. For safekeeping, all came permanently to rest in the Ottoman capital. The sultans are gone – their power is now wielded by the president of Turkey – but the relics remain. Topkapi Palace is now a museum, where visitors can still view the Holy Beard along with the other relics. Some rumors even state that it grows itself, so that portions can be cut off and given to important guests without detracting from the existing hair supply. The beard is in place most of the time, except for high festival days when its reliquary is brought out for display before the Muslim faithful. Truly, the legacy of Salman’s holy haircutting lives on![1]

9 A Stone Bowl

In the British Museum in London sits a carved stone bowl from Mexico. Its graven surface, simpler than some others of its kind, shows craftsmanship – carvings of the sun, feathers, etc. – but little to draw more than a glance by visitors. It’s easy to imagine it filled with corn or squash; it’s actually quite similar to bowls used to hold pulque, a Mexican alcoholic drink made from agave. Few would guess, from that single glance, that it was made to hold fresh human hearts. A cuauhxicalli was a bowl used by the Aztecs of pre-colonial Mexico during their well-known religious sacrifices. After the victim (willing or otherwise) was laid out on an altar, Aztec priests would cut the still-beating heart out of his or her chest. Once the priest had touched the heart to the mouths of all the religious idols present, the organ would be deposited in the cuauhxicalli until the priests were prepared to ritually burn it. Thus the humble bowl became the vessel for official offerings to the gods. Other cuauhxicalli were slightly more ornate, carved in the likeness of a jaguar or eagle. But even these embellishments would not suggest the bowl’s visceral purpose to the casual observer. The only feature that might do that would be the dark stains within.[2]

8 A Wooden Ladder

Most people would not assign any symbolism to this sort of object – after all, it’s a ladder. If pressed, the most they could say is that a ladder is a sign of moving up from one place to another – a symbol of connection and improvement. Yet on the contrary, one wooden ladder in Jerusalem instead symbolizes division and degradation. Christianity is split into tens of thousands of sects. Most Christians deplore this state of affairs, but accept it as a fact of life, even in Christianity’s most sacred spaces. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, understood by Christians to stand over the locations of Jesus’ crucifixion, burial, and resurrection, is no exception. There some of the biggest sects hold joint sovereignty; the Armenian Apostolic, Roman Catholic, and respective Greek, Coptic, Ethipian, and Syrian Orthodox Churches all share responsibility for maintaining the site. Unfortunately, this joint authority is often far from amicable. Governing by a committee seldom works well, and intra-faith squabbles routinely bubble to the surface. The simultaneous occupants are bound by a status quo agreement laid down in 1757. This agreement designates certain areas as common spaces, which cannot be altered without unanimous consent, while dividing the rest into minuscule and often absurd little territories. Some steps belong to one sect, while the landing at the foot of the staircase belongs to another. Moreover these microborders, like their larger cousins which separate nations, can become the subject of hot disputes. One small section of the church roof is disputed territory between Greek and Armenian monks, which sparked a freewheeling brawl in 2008 (video above). Which brings us to the ladder. Sometime in or before 1728, a workman performing repairs to the church façade placed a ladder below an upper-story window. It remains there today, due to uncertainty about which sect is responsible for the ladder and the inability of the occupants to agree on what should be done with it. It’s been used to deliver food to monks imprisoned in the church by Ottoman rulers, and once (in 1997) even stolen and hidden within the church. Once found, it was restored to its long resting place. The impasse continues despite its sad ridiculousness being pointed out by religious leaders. Pope St. Paul VI, worshipping at the site in 1964, was saddened by the way the ladder is a visible representation of Christianity’s splintered state. To encourage Christian reunion, he ordered the Franciscan monks who maintain the Roman Catholic presence in the church to refuse any proposals to move the ladder until the underlying divisions between Christian sects are erased. In the meantime, the Franciscans will veto any attempt to alter the state of the ladder. Until Christian ecumenicalism triumphs, it will remain what it has been nicknamed – the “immovable ladder.”[3]

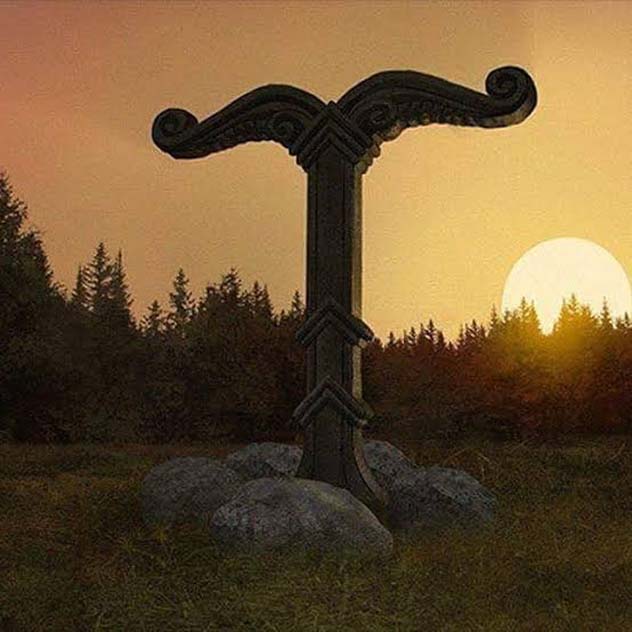

7 A Tree Trunk

If one came across a great gnarled tree trunk standing in the middle of a forest clearing, one’s first assumption would be that it grew there naturally. If told it had been placed there artificially, one might guess it was destined to be part of a bonfire. But if you were in ancient pagan Germany, you might be standing in the presence of an Irminsul – a sacred tree trunk. Trees hold particular significance in traditional Saxon pagan rituals – especially oaks or evergreens. Believers held these to be reflections of Yggdrasil, an enormous mythical tree that bears the entire world in its branches. These trees, either individuals or whole groves of them, would be dedicated to particular Germanic deities, and provided a focal point for worship or sacrifices. Apparently this veneration included both living trees and cut trunks or pillars transplanted to a new location. When Christianization was occurring in Germany, Irminsuls represented a direct pagan challenge to the process. Presumably, Saxon pagans believed that the trees to be inviolable, but zealous Christians did not suffer the presence of an Irminsul lightly. In 772, Emperor Charlemagne decreed the destruction of one in or near the Teutoberg Forest in northern Germany. Earlier in the same century, the missionary St. Boniface supposedly chopped down a huge oak tree dedicated to Thor, near the modern city of Kassel. It is doubtful that either the Christians or the pagans saw these actions as violations of live-and-let-live religious pluralism, the way most modern people would. More likely they interpreted either Christian missionary work or pagan resilience as causes of ultimate truth and fundamental belief, with two mutually exclusive truths being incompatible with one another. The Christians won out, and you won’t find a crowd of worshippers around any Irminsuls in Germany today. Germanic affection for great trees was not eradicated, however – as proven by the Irminsul cousins that stand in many living rooms each December.[4]

6 A Tooth

These days we tend to think of the fate of a person’s teeth as being the exclusive business of that person and their dentist. This view, however, ignores the multi-faith phenomenon of religious relics: the widely-held belief that the mortal remains of holy people are worthy of veneration, even the smallest separate portions. In some traditions, these remains (usually called relics) can retain the person’s holiness and, in and of themselves, bless the faithful who come into their presence. That’s how you get the Temple of the Tooth. Buddhist traditions say that upon the death and cremation of the Gautama Buddha, founder of Buddhism, surviving portions of his remains were divided amongst his followers and carried to far destinations, as the followers spread his message of simplicity and detachment. One of these, a single tooth, reportedly went as far as the island of Sri Lanka, in the capital city of Kandy. Buddhists gave the responsibility of guarding the relic to the king of the island; over time, possession of the tooth came to be seen as a spiritual sanctioning of the monarch’s right to rule. As centuries passed, many different monarchs built many different temples to house the relic; the current Temple of the Tooth (“Sri Dalada Maligawa”) was built in the early 1700s. The surroundings are ornate (as befitting a World Heritage Site). Elaborate carvings and decorations line the way to the tooth room. Within, the relic resides in seven golden caskets, which are set with numerous gems. The tooth is regularly brought out for processions; on Wednesdays, the tooth is ritually bathed in scented water, after which the water is distributed to believers as a healing element. Not all is peace and ritual at the Temple, however. It was bombed twice within nine years, by independently operating communist and secessionist groups (therefore being the only case on record where a tooth brought damage to Kandy, rather than the other way around). But the Temple has always been rebuilt, a testament to its importance in the spiritual and political lives of Sri Lankans.[5]

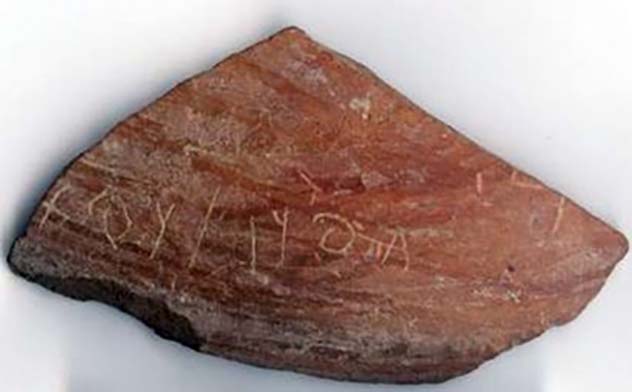

5 A Piece of Broken Pottery

Crockery, broken or whole, is a common category of artifact, since clay wares are relatively durable and were widely used throughout the ancient world. They are frequently used to study domestic culture, art, or trade networks, and are most interesting to researchers in those fields. It’s rather unusual, though, to come across a piece that gets Biblical scholars truly excited. Establishing the authenticity of persons, places, or things mentioned in the Bible is always a laborious exercise. Separating myth and legend from documented history is tough; much can depend on small bits of proof. In this manner, a piece of pottery discovered at Tell es-Safi, a Palestinian village near Hebron, provides some support for the biblical duel between the future king David and the Philistine soldier Goliath. Scholars have identified Tell es-Safi as the site of Gath, the Philistine village Goliath was supposed to have hailed from. But the existence of a village and the existence of a man are two very different things; some scholars have interpreted the entire David and Goliath tale as pure myth, storytelling inventions developed in an era long after their supposed combat. The pottery fragment (known technically as a “potsherd”) had something to say about this. Discovered during a dig in 2005, it bears an inscription with two names: Alwt and Wlt. These few simple letters caused a significant uproar among Biblical scholars at the time. Written in Semitic letters, the names themselves are non-Semitic, reminiscent of a people that moved into the region and adapted Semitic writing and other customs over time – fitting the traditional profile of the Philistine people. Both of these names are linguistically related to the most well-known Philistine name of all: Goliath. More importantly, the potsherd has been reliably dated to the early 9th or 10th century B.C., placing it within a century of the time of King David (according to standard methods of biblical dating). This does not mean the sherd belonged to David’s biblical opponent. However, it proves that the Goliath name and pedigree were in use, in the soldier Goliath’s hometown, in the approximate era that the soldier is believed to have lived. Since the name can be traced back to a contemporary historical context, it (at least) is demonstrably not an invention of a later period. [6]

4A Small Stone Box

The more important (and/or controversial a historical figure is, the more closely that figure’s record of existence is scrutinized. No one disputes the existence of, for example, the Greek playwright Diocles of Phlius, even though his work is barely known from a solitary ancient source. But with Jesus of Nazareth, who claimed to be God on earth, the matter is much more hotly debated. Skeptics also tend to disregard contemporary Christian writings as insufficient, due to the faith of the writers. As with the case of Goliath above, what is desired is independent confirmation through archaeological or documentary evidence. This brings us to a simple stone box discovered in Israel in the late twentieth century. It looks unremarkable, and would be unremarkable except for three factors: age, purpose, and inscription. The box is quite old; its limestone form dates to sometime between 20 B.C. and 70 A.D. Its purpose was to serve as an “ossuary” – a compact final resting place for human bones, often used when burial space is scarce. The Aramaic inscription reads: “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus.” When the ossuary’s existence was first made public in 2002, it quickly became the center of a firestorm in Biblical archaeology circles. Experts rushed to conduct tests upon it; some accused the box’s owner of forging the inscription; others speculated feverishly on the import of the inscription’s words. A professor at Tel Aviv University, reviewing the record of thousands of existing ossuaries, noted that the identification of the deceased’s sibling on an ossuary was extremely rare, probably only in cases where the sibling was considered a person of great importance. The professor also analyzed the likelihood of there being multiple people fitting the profile of the deceased (living near Jerusalem, named James, with a father named Joseph and a brother named Jesus) in the relevant time period, and found that likelihood to be extremely low. Chemical testing of the box has produced disputed results. Some analyses conclude that the inscription is modern, based on the chemistry of the surface inside the letters, while others point out that modern artifact cleansers can alter the chemical makeup of an object’s surface. The side promoting authenticity has produced other analyses, focusing on microfossils, which suggest the inscription is genuine and dates from the same time period as the box itself. Some Christians found the description of a “brother” of Jesus troubling, since traditionally Jesus of Nazareth was the only child of Joseph and Mary. However, longstanding Christian traditions point to the word used for “brother” being used just as often to mean “half-brother” (coming from a previous marriage of one parent) or “kinsman” (i.e., a more distant relative, such as a cousin). In fact, this very tradition already accounts for a man referred to as the brother of Jesus, James the Just, who served as an early bishop of Jerusalem and was martyred there in the 60s A.D. Christians venerate him today as a saint. So does the inscription point to an expert modern forger well versed in biblical tradition, or an authentic vindication of the existence of both Jesus and one of Christianity’s earliest saints? The verdict remains out. Since the ossuary is available for public exhibition, the curious may wish to seek it out for themselves.[7]

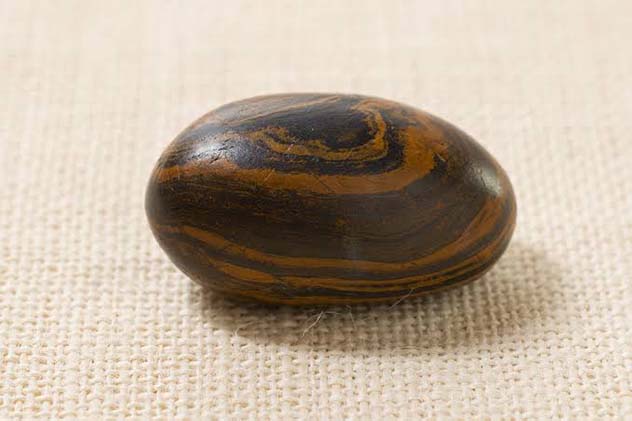

3A Brown Rock

In Salt Lake City, Utah, there is a smooth egg-shaped rock, with alternating dark brown and light brown layers giving it a striped appearance. This type of rock, dubbed “banded jasper” by geologists, is mostly comprised of iron and quartz, and is commonly found throughout much of the world. It would not be out of place as a paperweight or souvenir in a curiosity shop. This particular banded jasper, however, is one of the highly-prized artifacts of Mormonism. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints calls it Joseph Smith’s seer stone. Joseph Smith founded the Mormon church in the early 19th century, and throughout his life maintained his prophetic status through reports of his unique ability to access supernatural knowledge. One main way Smith professed to gain this knowledge was through the use of seer stones, certain rocks which would reflect special information back to a gifted observer. According to Smith, he had to view the stone in a very precise way in order to see with second sight. A witness to one of Smith’s sessions with the stone would have watched as Smith placed the stone in his inverted white top-hat, buried his face in the opening, and sat silently for long periods. Smith related discovering the stone while helping his neighbors dig a well; it is not known what attracted him to the stone in the first place, but he evidently kept it with him for many years. He was even hired by a treasure hunter to locate a lost Spanish gold mine in Pennsylvania using the stone; the effort failed, however, when Smith came up short and claimed an enchantment was blocking him from using the seer stone effectively. Though the stone apparently wasn’t powerful enough in this instance, it reputedly became the centerpiece of Mormonism’s foundational event, the finding and translation of the Book of Mormon itself. According to Smith, an angel appeared to him in the early 1820s, directing him to dig up golden plates that had been buried in a nearby hill. After unearthing them, Smith apparently used the brown stone to translate the strange writing on the plates into English, as described by a companion: “Joseph Smith put the seer stone into a hat, and put his face in the hat, drawing it closely around his face to exclude the light; and in the darkness the spiritual light would shine. A piece of something resembling parchment would appear, and on that appeared the writing. One character at a time would appear, and under it was the interpretation in English. Brother Joseph would read off the English…when it was written down and repeated to Brother Joseph to see if it was correct, then it would disappear, and another character with the interpretation would appear.” The early Mormon church would become divided over doctrinal disputes, the use of seer stones bring one of the contentious issues. Some Mormons wanted to use seer stones themselves; others said that Smith had lost his way when he stopped using them. No modern leaders of the Mormons utilize seer stones – but they still have Smith’s original, a fact which they revealed for the first time in 2015.[8]

2 A Broom

Outside of the professional maids’ industry, few people take much interest in brooms. Many will keep one around for household use, but that use may be sporadic, and the presence of a broom usually signifies nothing more than a minimal commitment to cleanliness. But for the Jain monks of India, possessing a broom speaks volumes about the deepest precepts of their faith. Jainism has several prominent monastic orders, but the monks in all of them keep a broom as part of their personal equipment. The design does vary by order, however. Svetambara monks use brooms of white wool, while members of the Digambara order arrange peacock feathers in a circle to form the tool. The broom is most often referred to as a dandasan. Jain monks carry their dandasan in order to gently sweep insects and other miniscule life out of their path, so that when they walk or sit they can avoid crushing these creatures. The reason for this is the Jain belief in the jivatman (soul), which exists in every living thing, large and small. Faithful Jains take a vow of ahimsa (nonviolence), promising to avoid causing harm to all forms of life. For a Jain monk, the constant carrying of his dandasan broom is a perpetual reminder of this belief, and a tool for living it out – rather than a sign of obsessive sanitation.[9]

1 A Sweat Cloth

Rare is the sweatband desired by third parties. Perhaps an occasional diehard sports fan will covet a used article from his favorite player, but these cases would be few and far between. Generally, people would prefer to leave alone any bits of cloth stained with the bodily fluids of somebody else. Obviously, though, the sweat cloth of Jesus Christ presents a special case. In Roman times, dedicated cloths were used for wiping away sweat, most often by soldiers, laborers, and craftsmen. Called a sudarium, the cloth could be tied around the head or simply carried and used as a towel. Christian tradition tells of multiple such cloths used to clean Jesus’ face during the hours leading up to the Crucifixion. One such cloth is known as the Sudarium of Oviedo, after the Spanish city that houses it. It definitely looks used; the 84 by 53 centimeter off-white cloth is covered with blood and sweat stains. Despite looking like something that would be quickly thrown away, it carries a long history of being valued. Much of that history involves evacuation. First mentioned as being present in Spain in the 600s – relocated there after eastern Christian lands were attacked by the Persians – it was moved again and again to avoid encroaching Muslim invaders. It finally came to rest in Oviedo in the 700s, where King Alfonso built a chapel to store it permanently. It’s been there ever since. Debates about its authenticity persist. Recent studies have tentatively dated the sudarium to the 700s, but the earlier documented history of the cloth (and the possibility of oil contamination of radiocarbon data) cast this conclusion into doubt. Other studies comparing the Sudarium to the more famous Shroud of Turin have found that bloodstains on both cloths share the same human blood type (AB), and blood patterns from multiple wound locations are consistent across both items. Science remains skeptical. However, the absence of a verdict has not stopped the flow of pilgrims traveling to see the Sudarium in Oviedo, a flow which continues unabated to this day.[10] About The Author: David F. Ellrod lives in Maryland with his wife, three daughters, and one very excitable dog.