“Ladies and gentlemen, a tap dance.” Taye Diggs’ lead-in sets the stage (figuratively and literally) for Richard Gere’s Billy Flynn to engage in some courtroom histrionics. Claiming “I’ve never lost a case,” Flynn’s tap dance is juxtaposed with him working over Velma Kelly (Catherine Zeta-Jones) and makes prosecutor Harrison (Colm Feore) look like a complete fool. He even manages to imply that Harrison is complicit in setting up Roxie. The coup de grace is when he furiously bangs the judge’s gavel several times, and then, out of breath, turns to the courtroom and exclaims, “The defense rests!”

Admittedly, the movie is probably a little kitsch, but Reese Witherspoon’s portrayal of Elle Woods catapulted her into the stratosphere of Hollywood. The scene that stands out is when pool boy Enrique, rumored to be the lover of accused murderess Brooke Windham, is examined by Emmett (Luke Wilson). While getting a drink of water, Enrique snaps about not tapping her Prada slacks at him. She becomes convinced that he’s gay and is lying. Only Emmett believes her, and ingeniously baits Enrique by finally asking him, “And your boyfriend’s name is..?” to which Enrique responds, “Chuck,” thereby falling into Emmett’s trap.

For all of the knocks about Matthew McConaughey, his closing summation in A Time to Kill is one of his best acting performances. After floundering to save defendant Carl Lee Hailey, his character Jake finally hears Carl Lee’s argument that he is “one of them,” that is, a white man in the Deep South. No matter who he claims to be, Jake will still be seen as “one of them.” Carl Lee asks Jake to use that to advantage, and Jake does so as he delivers a solemn closing argument that extols the nature of man, and how pervasive double standards are.

Played with the usual “aw, shucks” demeanor by the late great Jimmy Stewart, defense attorney Paul Biegler is assigned to a murder defendant whose wife has had an affair with the victim, Quill. After being railroaded by both the prosecution and the judge, Biegler finally appeals to the judge and laments that the prosecution is presenting its case based on circumstantial evidence. He compares it to “removing the core from an apple without removing the skin,” and begs the judge to “let me cut into the apple.” After the prosecution attempts to object to his methods, the judge, reluctantly, overrules the objection, setting up a dramatic finish, including a fantastic summation from George C. Scott.

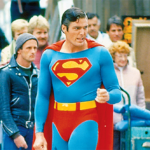

Edward Norton’s film debut couldn’t have started off any better – he received a Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination. Playing murder defendant Aaron Stampler, a stuttering altar boy, Norton is put on the stand by prosecutor Laura Linney, and, true to form, stutters, and has trouble answering her questions. Until, that is, he is pushed too far, and his altar ego “Roy,” a violent sociopath (and no stutter), emerges. He jumps over the box and begins to choke her, threatening to break her neck. This is enough to get him confined to a mental hospital. However, it turns out that it was all a ruse – as the defendant responds to his attorney Martin Vail (Richard Gere again) that “there was never an Aaron, counselor.”

Both leads (Fredric March and Spencer Tracy) were multiple Oscar winners, and it shows. Based off the Scopes monkey trial, Drummond (played by Tracy) is being stonewalled by Brady (March) and the judge, so he resorts to his last option: putting Brady on trial as an expert on the Bible. Brady starts out confident, but after pointing out that “if the Lord wants a sponge to think, it thinks!” Drummond is able to trap Brady in the uncertainties of the Bible, and how it contradicts itself. Ultimately, while his client Cates is found guilty, Drummond’s argument is enough to get Cates off with a slap on the wrist. A powerful performance from both of these men.

We all know this scene for Jack Nicholson’s memorable quote, “You can’t handle the truth!” However, the entire testimony from Col. Jessep and the cross-examination from Tom Cruise makes this scene brilliant. Additionally, Kevin Bacon, representing the military, force Cruise to be on his toes the entire time; how he manages to trap Jessep in his lies is no small feat.

In actuality, both Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep’s testimony in their custody battle is moving and certainly relevant. However, Streep’s Joanna Kramer is able to express her love and fears and hopes for their son Billy, all the while being badgered by Ted’s attorney. She keeps persisting that “it (the marriage) wasn’t a success,” but the attorney argues, “Not it, Mrs. Kramer. You.” Finally, they both snap and Joanna tearfully admits her mistakes. It’s likely that this scene is the clincher that gave Meryl Streep her first of three Oscars.

This film certainly has the best ending of all these films, both for the twist and for the superb performance of Marlene Dietrich, Charles Laughton, and Tyrone Power. Defended by Sir Wilfrid Robarts (Laughton), murder defendant Leonard Vole looks unlikely to win his case when his wife Christine (Dietrich) makes the controversial decision to testify against him (despite spousal privilege applying), indicating that he is guilty. After receiving a phone call from an anonymous woman that discredits Christine’s testimony, Sir Wilfrid is able to get Vole off. But in the twist, it turns out that the anonymous woman was Christine herself. The ending can be summed up in two lines: “You knew he was innocent, and I understand that.” “No, Sir Wilfrid, you have it all wrong. I knew he was guilty.”

I think to many, this one was no surprise. Gregory Peck’s portrayal of Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird not only won him an Academy Award, but also was named the greatest movie hero of all time, ahead of Luke Skywalker, Indiana Jones, and numerous others. While defending Tom Robinson, and knowing he isn’t going to win despite evidence that Robinson couldn’t have done it, Atticus barely raises his voice. He begs the court to “believe in Tom Robinson,” Peck’s baritone voice demonstrates everything that is indeed heroic about Atticus Finch. The ending of the scene is one of the amazing moments in cinema – as Atticus solemnly puts away his attache case and walks out of the court room in defeat, what Reverend Sykes says next to Scout Finch demonstrates the immeasurable respect Atticus has earned: “Miss Jean Louise, stand up. Your father’s passin’.” And with that, Atticus leaves the courtroom, knowing that while he had little chance, it was his duty as a father and a man to fight for justice.