10The Location Of Agade

Nearly 2,000 years before the Romans stitched their continent-straddling empire together, the Akkadian Empire was in full swing. Stretching from the Mediterranean to the center of modern-day Iran, it was a hotbed of cultural activity. Sculptures and frescos were so far ahead of their time they’re now considered the pinnacle of ancient artwork. A strong literary tradition sprang up, leading to the preservation of the oldest Semitic dialect known to scholarship. At the center of all this lay the city of Agade, the origin of Akkadian culture and one of the most important places in Ancient Mesopotamia. It influenced events as far away as Babylon and modern-day Oman. Today, we have absolutely no idea what happened to it. We know it collapsed, probably as a result of invasion, but beyond that? Nothing. We don’t even know where it used to stand. There are contenders for possible sites, notably the mound at Ishan Mizyad, but we’ve so far found nothing to indicate the greatest city of the period once stood there. Until something turns up, Agade’s location and fate will remain a total mystery.

9The Literature Of the Indus Civilization

All we know for certain is that it is indeed a language, although even that point is frequently disputed. Most artifacts containing Indus writing rarely feature more than five characters (which only repeat rarely), so it’s been argued that it may not constitute a genuine written language. While most experts disagree with this assessment, we’re still in the position where deciphering whatever they wrote is next to impossible. Although many claim to have broken the Indus “code,” none of their translations are widely accepted. So what’s lying in wait behind those symbols? It could be anything: administrative documents, prayers, fragments of fables, or dirty jokes. Whatever it was, it’d give us an unparalleled behind-the-scenes look at one of history’s great cultures.

8The Fate Of Boudicca

A gigantic warrior queen who destroyed the capital of Roman Britain, sacked London, and slaughtered as many as 70,000 people during her rebellion, Boudicca remains a household name nearly 2,000 years after her death. That she died after an epic battle with the Romans is indisputable. How she died, where she died, where she was buried, and where that battle was held are all a mystery. Although tradition states Boudicca drank poison after her horrendous military defeat, we have no evidence for this beyond Tacitus’s account. The Greek writer Dio Cassius claimed she died from illness. Their two accounts differ in other specifics, too, including the reason for the rebellion and Boudicca’s funeral. According to Dios, she had a lavish burial, which is the origin of the rumor that she’s currently somewhere under Kings Cross Station. But this goes against nearly everything we know about the death customs of Iron Age Britons, who would probably have disposed of her body in a less elaborate way. Even the site of her famous defeat has been lost to history. For a battle that shaped Britain for the next few hundred years and killed over 80,000 people, that’s nothing short of incredible.

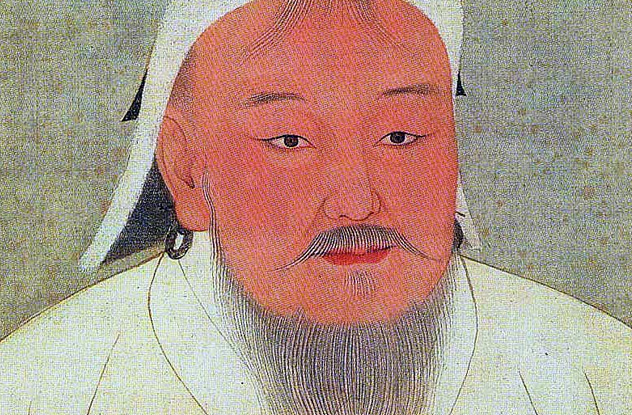

7What Genghis Khan Looked Like

Genghis Khan was the founder and ruler of the largest contiguous empire in history. Everything about him is so well studied that even age-old mysteries like the location of his tomb may soon be solved. There is one puzzle we’re guaranteed to never solve, though. We have no idea what Genghis looked like. Incredibly for a narcissist who killed so many millions of people it affected the planet’s climate, the Khan left behind no likenesses whatsoever. Not a single portrait or sculpture has survived—if there were ever any in the first place. The few glimpses we get of history’s most prolific killer come in prose, and nearly all of those are wildly contradictory. While many accounts describe him as ethnically Mongolian, one text claims he had green eyes and flowing red hair. Seemingly the only thing they agree on for certain was that he had a beard.

6The Origins Of The Bell-Beaker Folk

Although they sound like something to do with the Muppets, the Bell-Beaker folk were one of the most important cultures in ancient Europe. Wherever they turned up, copper weapons, bronze jewelry, advanced archery equipment, and their iconic drinking vessels would appear not long afterward. They were harbingers of the Bronze Age. In ancient Britain, they even redesigned Stonehenge. Yet we have no idea where they came from. It’s like they just appeared out of thin air. Although we can trace aspects of their culture back through the ages, they tend to crop up in places where it doesn’t make any sense for them to be. This has led many to speculate that they were less a single culture than a cross-cultural phenomenon—kind of like if people in the future dig up iPhones in China and conclude US invaders brought them. But that doesn’t explain why Beaker folk buried in Germany all have DNA similar to modern Spaniards and Portuguese. Where did they come from, and why did they suddenly decide to spread across Europe? We’ll probably never know.

5The Reason For Constantine’s Conversion

Constaintine ruled the Roman Empire in the fourth century, and his shock conversion turned Christianity into one of the largest faiths on Earth. Prior to Constantine’s conversion, the best Christians could hope for in the Empire was a kind of begrudging indifference. What caused this epoch-shaking act of faith, however, is far from certain. The best-known story, passed down by Lactantius, claims Constantine had a dream the night before an important battle, and a handy monk interpreted it from a Christian standpoint. On the other hand, Eusebius says a vision of God appeared above the battlefield, demanding Constantine decorate his shield with the symbol of Christ. The two writers also disagree on where and when the conversion took place and whether it followed or preceded a battle. Then there’s the thorny issue of whether there was any dream or vision at all. Plenty of scholars over the centuries have suggested Constantine’s conversion to a religion popular among soldiers stemmed less from genuine faith and more from an overwhelming lust for power.

4What The Olmecs Wrote About

In the early 1990s, villagers in Veracruz, Mexico accidentally made one of archaeology’s greatest finds. A stone block they dug up turned out to be covered in ancient writing that predated the Zapotec system by hundreds of years. Carved by the mysterious Olmec civilization, it bore signs of distinct sentences, error corrections, and even what might be poetic couplets. It also had all the hallmarks of being a private copy, so other documents detailing Olmec court records, trading routes, and even literature almost certainly exist. But the writing proved to be utterly indecipherable. As the earliest known writing system in the Americas, Olmec is unlike anything else we’ve encountered. That makes deciphering it virtually impossible unless we happen to stumble across a new Rosetta stone—a possibility so unlikely we’d be better just giving up altogether. Frustrating as the puzzle of Indus script is, this is even worse. Aside from being the first on the continent, Olmec script appears capable of handling complex stories, detailed records, and in-depth religious traditions. One of the most valuable cultural hauls in history is likely locked away from us forever.

3Why Harold Wilson Resigned

On March 16, 1976, Prime Minister Harold Wilson did something no British leader has done since. With almost zero warning to his government, he took to the airwaves and announced his resignation. His actions set the course of British politics for decades. When Wilson went, James Callaghan took over as PM and proved so spectacularly incompetent that a virtual nobody who went by the name of Margaret Thatcher managed to carry the next election. Without Wilson’s momentous decision, the modern UK would be a very different place. This all makes it even weirder that we don’t know why he did it. Although Wilson claimed he wanted to give Callaghan a chance to settle into the role, almost nobody believed him. The Labour government of the time was unstable and only had a majority of three in the House of Commons—the last thing it needed was more instability. As a result, theories about why Wilson jumped have ranged from early signs of Alzheimer’s to knowledge that MI5 were planning a coup. To date, none have proven conclusive.

2Why The Romans Built Their Border Wall

For the first 600 years of its existence, Rome was in a state of continuous expansion. Romans fought wars, conquered nations, and gained territory that stretched over a far wider area than the current European Union. Then, in A.D. 117, Hadrian stopped. Scotland was abandoned to the barbarians, expansion slowed or halted, and the Empire froze. In the place of new territory, gigantic walls sprang up, encircling its lands. Common sense would tell us the walls were to repel invaders, but common sense would probably be wrong. We know from garrison reports that life guarding Scotland’s border was less the opening scenes of Gladiator and more a very boring life of standing in the rain. There are virtually no references to fighting on the British frontier and few anywhere else. In parts of the Empire, the wall was nothing more than a couple of tiny shacks holding three people, many miles apart, which was hardly enough to stop a barbarian invasion. Today, it’s thought that these garrisons were less about defense and more about controlling valuable trade routes. Yet even then, we’re only guessing. Why build something as impenetrable as Hadrian’s Wall just for trade? The billeting of all available men at the frontiers let the barbarians sweep over the Empire once they broke through, so the reason for the walls would help us understand why Rome finally fell. It could also teach us a thing or two about our own border walls, from the US-Mexico wall to India’s border with Bangladesh.

1Nearly Everything About Early Anglo-Saxon Times

A vital question for historians is always how reliable a source is. This stops us from accepting hoaxes at face value or drawing important conclusions from the ravings of a madman. But what if the ravings of a madman are all you’ve got? Welcome to the study of early Anglo-Saxon Britain, where everything we know comes from the writings of a single, deranged monk. Gildas was certifiably insane. Obsessed with the End Times, his only major work was a screed written against the post-Roman kings of Britain, condemning them for their excesses. This screed is our only contemporary account of the period, and it’s so full of holes that it just creates more mysteries. Of the five kings Gildas rails against, we know almost nothing about two of them or how they fit into lines of succession. Since most of what we know about the other three comes from Gildas himself, it’s impossible to tell what’s true and what’s propaganda. Then there’s Gildas’s habit of simply omitting vital information. At one point, he mentions a bone-shaking battle between the Britons and the Anglo-Saxons that ended with British victory under a great leader. For reasons unknown, he leaves out the leader’s name. Finally, there’s the simple fact there must’ve been whole battles, armies, and royal families Gildas didn’t think worth mentioning—names, dates, and places now utterly lost to history. As far as sub-Roman and early Anglo-Saxon Britain goes, we’re in the dark.